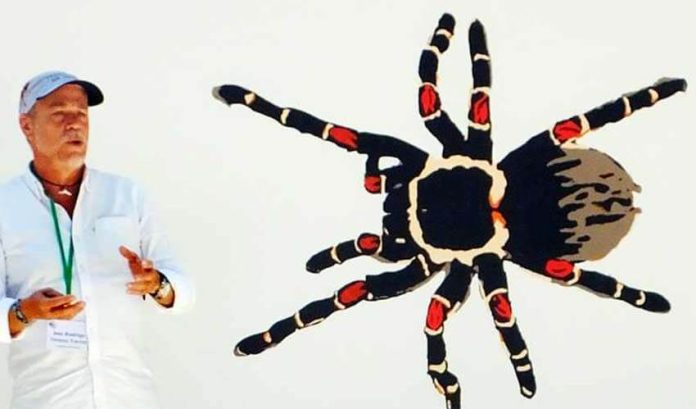

In 2002, the government of Mexico authorized a project aimed at saving the Mexican tarantula from the damage inflicted on the species by poachers. Rodrigo Orozco, a Mexican who initiated that project and ended up making it his life’s work, said that illegal trafficking of tarantulas has been “radically reduced” over the last 20 years.

“I’m not saying it’s all due to my project, because others have taken up the cause over the years, but the change is dramatic,” Orozco said. “In 2002, trafficking tarantulas was widespread, and you could find illegal Mexican tarantulas in [the Mexican retail chain] Liverpool and even in India. You could buy them in big-name department stores! Today, you are very unlikely to find an illegal Mexican tarantula in the market anywhere. It would be very rare.”

This change has come about, according to Orozco, because today the United States and Canadian markets are saturated with tarantulas raised in captivity, provided by his and five or six other organizations in Mexico.

Another key factor in this change, Orozco explained, is an increasing awareness among tarantula aficionados:

“People are going to our Tarántulas de México website, where they discover hard facts about the difficulty of raising tarantulas, as well as solid reasons why tarantulas should not be kept as pets,” he said. “Our website is in Spanish and English, and right now, it’s the most-read page on the internet for information on tarantulas!”

I asked Orozco what had inspired him to start a project like this 20 years ago.

“I used to live in parts of Mexico where there was a lot of jungle. So I got to know and love the creatures of the jungle, including, of course, spiders and tarantulas. And I noticed that everywhere I went, I could find tarantulas for sale in markets and pet stores, and I imagined they were all coming from some kind of tarantula farms,” he said. “But I couldn’t figure out how those farms were able to produce so many mature tarantulas because these creatures grow very, very slowly. A female only reaches sexual maturity after 10 years, and it would take 20 years for her babies to reach the size I was seeing in all those shops. So I wondered just where all the tarantulas were coming from.”

Orozco decided to put his question to the man in charge of the local office of the federal Environment Ministry (Semarnat), asking him where he might find one of those tarantula farms.

“What?” the official replied.” There’s no such thing as a tarantula farm.”

“Then where do all those tarantulas come from?” Orozco asked.

“What tarantulas are you talking about?” the Semarnat man asked. “Where did you see them?”

“Everywhere!” Orozco said. “All kinds of huge tarantulas in every market.”

“Oh, those!” the representative answered. “Todas son ilegales [they’re all illegal]. They were taken from the wild.”

Orozco, at the time a young man who had walked in from off the street, then told the official in charge of protecting wildlife, “Can’t you see this is an ecological disaster? If you take one tarantula out of the wild, it’s going to take 20 to 40 years before you’ll ever find another tarantula there because they are very slow-growing. The damage would be irreparable.”

He walked out of that office totally disheartened.

“That’s when I decided I would begin to seriously study tarantulas,” he told me, “their diet, their mating behavior, everything. I would learn how to start my own tarantula farm, and then I would flood the market with them so nobody would take them from the wild anymore.”

“But guess what?” he said. “There was no information on tarantulas anywhere in Mexico.”

He went to Guadalajara, where there was nothing in the libraries. Then he went to Mexico City, where all he could find was one thesis in the National Autonomous University library; it had only a little information on tarantula reproduction.

“So I started talking to and writing to biologists, and when they heard my plan, they shut the door in my face,” Orozco said. “Nobody wanted to listen to me.”

Orozco’s luck changed when he managed to contact Canadian Rick West, whom he refers to as “the pope of the world of tarantulas.”

West liked Orozco’s idea of flooding the market with tarantulas raised in captivity and urged him to attend an upcoming meeting of the American Tarantula Society in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

“So I went to the USA just for this meeting, and everybody kind of looked at me as if they were thinking, ‘What is this Mexican doing here?’ Well, people were milling about when suddenly the crowd started whispering to one another. They were all excited because the famous Rick West had just arrived. Then West walked in and stood there before that crowd, and the first thing he said was ‘Rodrigo, come on over here with me!’ And suddenly, I was turned into ‘Rick West’s Mexican friend!’”

At this symposium, West introduced Orozco to Stan Schultz, author of The Tarantula Keeper’s Guide, which Orozco said is the bible for raising tarantulas and still the best book on the subject.

Orozco returned from Carlsbad filled with enthusiasm and registered his project as the first legal UMA (Wildlife Management Unit) in Mexico dedicated to tarantulas.

“Once I was registered,” he said, “I started to receive all the illegal tarantulas that the Mexican government was seizing at airports and such, and it was these confiscated tarantulas that I bred, and soon I had 5,000 young ones growing in my parents’ house.”

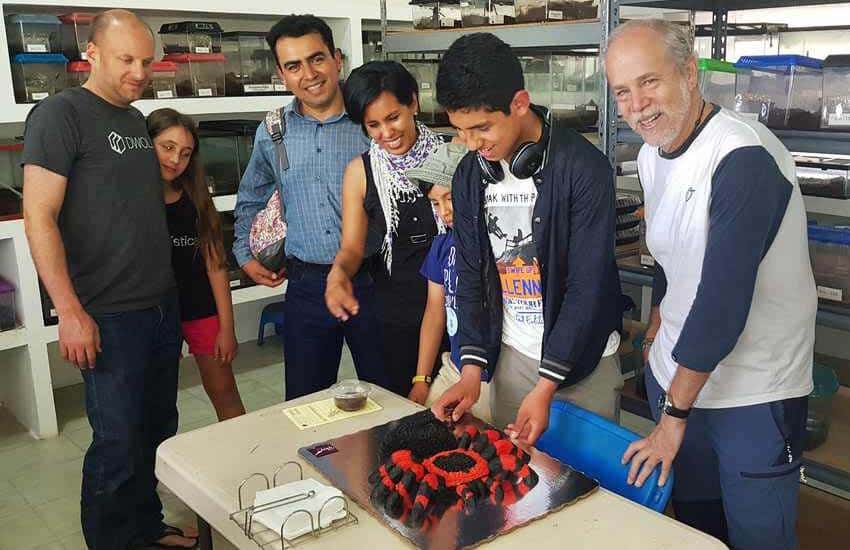

Today, Orozco’s tarantula sanctuary is located in the hills of Pinar de la Venta, just outside Guadalajara. From here, he ships legal, certified tarantulas all over the world and also receives visitors, who typically arrive feeling somewhat twitchy, only to leave utterly charmed both by Orozco and by the big and hairy but oh-so-gentle arachnids they are able to hold in their hand for a few precious moments.

It is just my personal opinion, but it seems to me that between 2002 and 2022, one man with an idea — one man with intent and persistence — saved a species.

All that time, including right now, he operated in the red, and in all that time, neither his government nor any organization nor any Mexican millionaire was willing to lend a hand. Not even the tarantulas know why they are still walking about safe and happy, but I know — and now, dear reader, so do you.

The tarantula management unit is open to visitors on weekdays, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Just ask Google Maps to take you to Tarantulas de Mexico, Pinar de la Venta. Driving time is about 30 minutes from downtown Guadalajara.

• For more information, contact Rodrigo Orozco at 333 968 7805.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.