“Yes, we were in La Cueva Cuata for six hours and never got to the end of it; finally crawled out at two in the morning!”

Inspired by that report from a friendly stranger, we began our search for La Cuata Cave, which — we had been told — was set in a precipice overlooking the Santiago River in the Santa Rosa Valley, which is located about 50 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara.

It was January of 1990, in “the dead of winter,” but as we drove down the winding road into the deep Santa Rosa Canyon, we were pleasantly surprised to find all sorts of tropical fruits already ripening. We made our way through sleepy pueblitos with strange names like Achio and Chome, past tamarind trees, golden fields of corn, flowering apricot trees and enormous mango trees drooping with fruit. Throughout the dry season, the many springs in the area keep the vegetation eternally green — and the roads eternally muddy.

A local resident named Arnulfo had heard of La Cuata and was willing to take us to the cave, though he had never actually entered the place and was none too anxious about doing so now. Leaving our Jeep under a shady mango tree, we hiked northwest along a narrow trail that passed banana plants and papayas until suddenly we caught sight of the majestic barranca in the distance.

“The cave is right at the edge of the precipice,” explained Arnulfo. “I just hope I can find it …”

That problem resolved itself a few moments later when we came upon a rancher who introduced himself as Don Guadalupe, “the one in charge of visitors to the cave.”

Well, we couldn’t quite believe we’d found a tourist cave in this lonesome spot, so we pried Don Guadalupe for more information.

“Pues, people come to this spot to pray, because, bueno, there’s something special about it. You see, when the world comes to an end — and it’s coming very soon — only seven places will be spared, and this cave is one of them! People call it La Cuata but we call it La Cueva de Tequilizinta.”

Pulling out my pocket agenda, I inquired as to the precise date when the world would be ending. “Why, in 1998!” exclaimed our guide with a knowing look.

A little while later, the trail ended right at the base of a sheer wall. Facing us was a dark hole in the cliff side and around the bend to the right was a drop of a good 100 meters straight down to the Santiago River.

I stepped into the cave entrance and I removed my pack. “Here’s the cave!” I shouted to my compañeros coming up the trail.

“No, this isn’t it,” said Don Guadalupe. “We have two caves here. That’s why they’re called Cuevas Cuatas. The one we want is right above this one,” he said, pointing straight up.

Since this cave was located in a sheer cliff wall, my wife Susy queried how we were supposed to get to another spot above us. Don Guadalupe gestured toward the edge of the precipice: “Just follow me!”

Hugging the wall, this hardy little man began to edge his way right over the long drop down to the Santiago River. The rest of us looked at one another, gulped hard and, with Susy in the lead, cautiously followed our guide, imitating his every move and trying not to look down. After a few meters, the “trail” mercifully switched back and we moved upward to the entrance of La Cueva de Tequilizinta.

The mouth of the cave had been converted into a kind of chapel, complete with altar smothered in candles. Something told me the first prayers said there were probably of thanksgiving for having made it alive. Beyond the altar, the passage disappeared into darkness. Half crawling and “Groucho-walking,” we followed a sort of trail marked by many, many muddy footprints. The passage was about four meters wide and anywhere from a foot to just over a meter high.

We arrived at a fork. “Go to the left, not the right!” warned Don Guadalupe, explaining that the right-hand passage led to a trampa — a trap — devised by the Indians who had used this cavern in ancient times. Naturally, we pressed him for details.

“The last person who went that way stepped onto a rock that operates on a swivel. As soon as he put his weight on one end of it, the rock flipped over and that man slid down a chute that shot him out of the cliff wall. They found his body down by the riverside.”

Naturally we heeded this warning and followed the left fork to a totally dark room where there was another altar — and plenty of mud.

Several weeks later we were back at Tequilizinta Cave with several friends. This time we had brought survey equipment and a length of nylon webbing to which we planned to tie Jesús, one of our compañeros who had volunteered to go first into the “Deathtrap” passage.

Groucho-walking once again, we made our way further and further from the entrance and daylight to the Y where Don Guadalupe had sternly warned us to keep left.

This time, however, we turned right and after some 30 meters we came — not to a violent death flying through the air, but to the edge of a wide pool of shallow water in which were floating numerous globules of gooey, black, vampire bat droppings. As I happened to be wearing tennis shoes, I was elected the honor of splashing around in this foul-smelling drink to see if the passage continued. It didn’t, but then the question came up: how are we going to survey this little lake?

“Well, John, seeing that you are already standing in it …”

Have you ever tried to survey an underground lake by yourself? Especially a smelly lake with a ceiling so low you can’t stand up straight? I won’t vouch for the measurements I took, but who’s ever going to check them out?

[soliloquy id="116768"]

One unexpected benefit from mapping the “Black Lake” was the discovery of lava stalactites on the roof. Both of Las Cuevas Cuatas, this one and the cave directly beneath it, turned out to be the very first lava tubes ever surveyed in Jalisco.

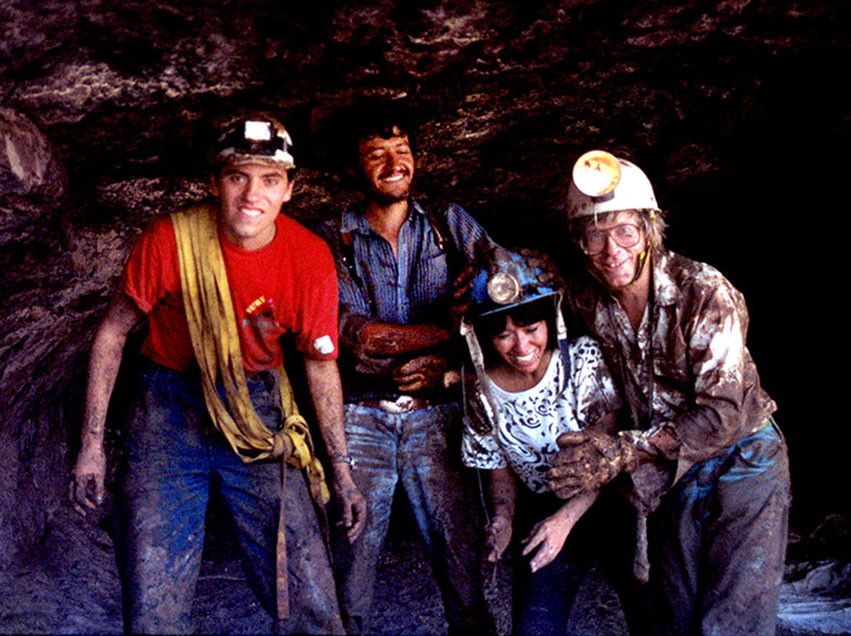

Having found nary a sign of the infamous death trap, we surveyed our way back to the Y and followed the other passage right into El Pasaje Chicloso, the Sticky Room, where the cave finally came to an end. As we dragged our bodies and bags of gear through the thick mixture of mud and clay — a veritable Paradise for Pigs — our flashlights, compass, tape and boots all slowly turned into indistinguishable globs of mud — and so did we.

On later visits to La Cueva de las Cuatas, we explored the top of Tequilizinta Mountain, where we discovered the long abandoned homes of the religious community that had once held ceremonies inside the cave and who, according to Don Guadalupe, “left Tequilizinta to follow a new Messiah, all of them except me.”

The hike to Tequilizinta is described in Outdoors in Western Mexico and you can find the driving and hiking route on Wikiloc. If you go for a visit, be sure to walk to the edge of the precipice, located only 25 meters east of the last house in the ghost town, for a spectacular view of the Santiago River, and just in case the world comes to an end while you’re up there, rejoice: you couldn’t be in a better place!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.