I’m typing this in Heroica, a taproom in downtown Veracruz, a beer by my side. To any observer, I look like a digital nomad living her best life. You can almost smell the housing prices rising unsustainably around me.

Alas, it’s just a facade only. Am I really a nomad if I’ve been living in the same place for decades, since before online work was a thing? Online work became a thing once I’d been here for 10 years already. In any case, the technicalities don’t really matter.

My first jobs in Mexico were in the fields of education. For an English-speaking foreigner, that was pretty much the job you could get, after all. The first was quite exploitative. I was paid in cash, worked an awful split shift and the promised help with getting my work visa never arrived.

Young and in love, I hardly noticed that my boyfriend and I had no furniture save a bed, a fridge and a plug-in stovetop in our tiny fifth-floor apartment. A computer we eventually bought sat on a metal chair that had been left behind by a previous tenant. We’d sit on the floor to use it, and dream of one day owning a microwave and a sofa.

The online revolution

Things have changed since then. In 2011, I got my first online job at Open English, an English-teaching platform for live classes. I was good, made good money for Mexico and moved up the contractor ladder as time went on.

Soon, though, the company was spooked by a worker who sued for misclassification as an independent contractor when we all clearly did the work of employees, and everything good about working there disappeared. I don’t blame the person who sued, mind you; it was bound to happen sometime.

Soon after, I got a job at an online Chinese company. We gave individual classes to Chinese children at what for them was afterschool time but for me were ungodly hours of the morning. The pay was good and the students were nice. Even without benefits, as we were also contractors, especially those of us living outside of the U.S. lived well. Eventually, things started slowing down, and I decided to jump ship before it sank.

Like a rolling stone

No matter! I was tired of teaching anyway. Now, I would make my fortunes as a writer and translator. It was during that time I pitched to Mexico News Daily’s then-owner and began to write. This was also the period that I honed my skills as a subtitler, and for several years I made fairly good money — again, “for Mexico” and without benefits.

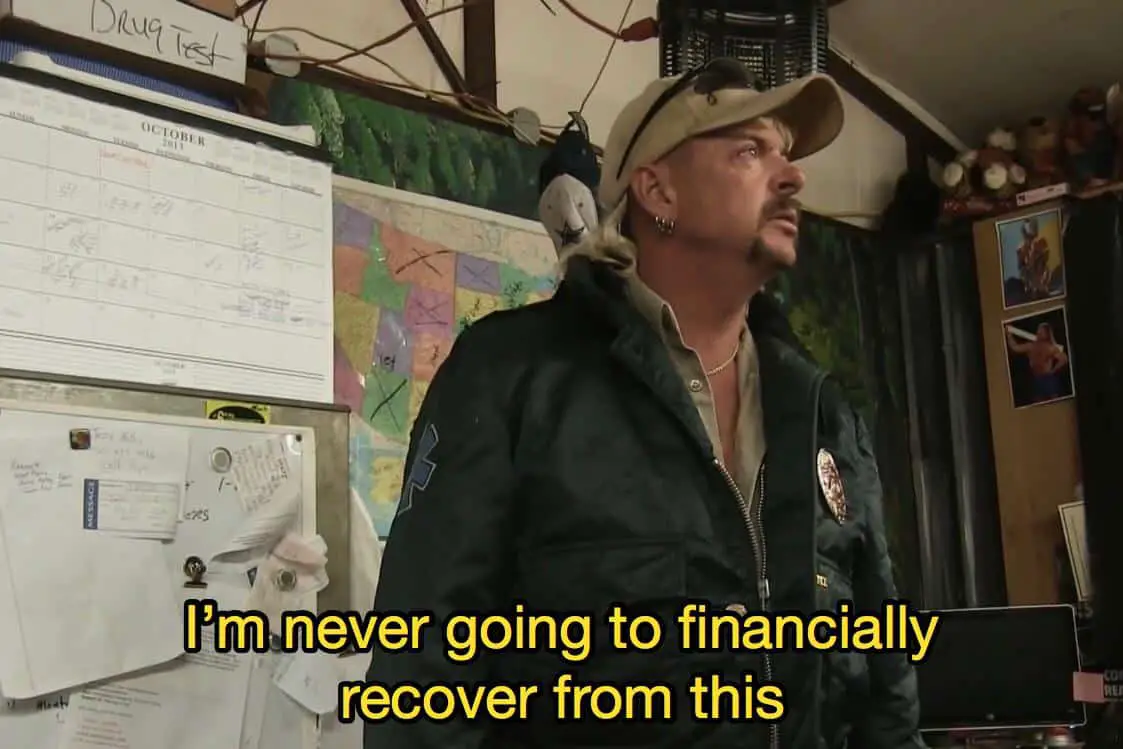

Then, last year, I was elated to finally be hired as a full-time remote employee at a U.S. company where I’d worked as a freelance editor. That kind of job had long been a dream! Alas, it was not meant to last; I was let go after about nine months. By then, of course, I’d told most of my freelance clients, except for this paper, that I’d be less available. I wish I hadn’t, because by the time I contacted them again, they’d moved on.

When the job goes away

Like any job out there, there’s no guarantee that an online job you secure will be there as long as you want it. Surprisingly, my own experience was that freelancing turned out to be more stable than my full-time W-2 job.

Since then, the landscape has been rough. Suddenly, many U.S. employers are insisting that you do the work — even if it’s online contract work — within the U.S. Why?

The main reason that companies give is that they don’t want to get sucked into messing with the tax obligations of other countries. Working virtually in one country and being subject to the tax system of another is, of course, complicated.

I also suspect, though, that for U.S. companies, workers in Mexico are supposed to mean reduced labor costs. If an employer has to pay someone in Mexico just as much as someone in the U.S., what’s even the point for them?

As I wrote last week, companies are expected and encouraged to cross borders when it’s in the owners’ and shareholders’ best interests to do so. But let workers do the same, and suddenly your labor savings go out the window! Who will work as engineers for US $1000 a month if those workers can just move, virtually or physically, and get five times that? “How are we supposed to game the system if you’re gaming the system?”

When it comes to capitalism, it’s the capitalists that benefit, after all. The tide has been turning against worker stability for quite a while now, but my perception is that it’s reaching a breaking point. The lack of stability and benefits, for everyone, is unsustainable.

Sticky ethics

I struggle with admitting that I need beyond a Mexican salary to live. But I do; most Mexicans do too, which explains many immigration patterns over the past century. We all want to live well, and we all want to provide for our families.

As I’ve discussed before, when you live in a country without the support of your birth family, money is what compensates for that lack of support. Basically, it’s “support for purchase” in the form of things like insurance.

Also, your budget adapts to what you are used to spending. Pair this with the eye-watering rise in prices all over the world, and it’s easy to see why so many people are in a tight spot.

So what’s my point in writing all of this?

It’s a cautionary tale, my friends. Save a lot, if you’re able, and have a Plan B. Having an online job does not mean you’ll get to keep an online job. Between AI, U.S. companies cracking down on the residency question and a tricky job market with lots of fake job postings, the job-searching landscape is sure rough out there. Give your own business a try, perhaps: then at least it depends on you, and not a company whose goal is to enrich and provide stability for someone else.

The bright side is that here, unlike many places in my home country, the bare minimum costs less. You won’t go hungry, and you’ll have a roof, even if it’s not the roof you want. Another silver lining? Mexicans have less of a tendency to blame a lack of individual financial achievement on your lack of gumption and go-getism.

Sarah DeVries Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.