What is the definition of privilege?

To me, one’s privilege is defined by being able to really mess up, sometimes badly, and either to be exempted from the consequences or to suffer only the most minor kind.

So here’s a litmus test: if you make just one wrong move, are you done for? Or can you make dozens of wrong moves and still be all right, ready to move on to your next mistake?

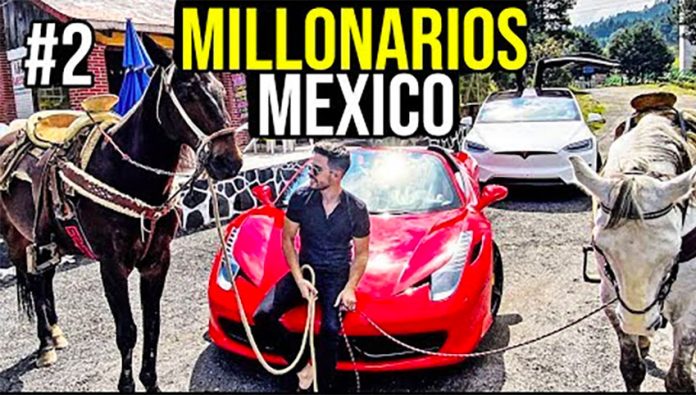

The article about Mexico’s “eccentric millionaires” and my almost visceral reaction to the video of some rich dude driving around like he was the self-appointed king of Mexico got me thinking, once again, about the dynamics of privilege both here and abroad. If you can get through the video without feeling actual physical disgust, count me impressed.

In Mexico as in most other places in the world, privileged adults tend to have been privileged children. Hard work counts, of course, but being able to get the kind of education needed to rise up in a capitalist society — and to have one’s bad mistakes swept under the rug — keeps some people far ahead while others struggle with a combination of lack of opportunities and bad luck.

Some privileges show themselves biologically: a woman who makes the “mistake” of unprotected sex could be faced with the prospect of either caring for another human being for most of the rest of her adult life or going to jail for aborting, depending on where she lives; a man who makes that same mistake can carry on with his life as if nothing had happened.

Some privileges show themselves legally: a millionaire can get friendly waves and peace signs from police officers as he speeds by at over 200 kilometers per hour while poor citizens might be pulled over and have their car taken away if they can’t pay a bribe.

In the United States, a rich white kid like Brock Turner can get just a few months in jail and probation for raping an unconscious woman while black people are continuously killed by police officers who feel even a hint of suspicion that they want to cause harm. The former CEO of Amazon México was at least initially given a pass even after most evidence pointed to him having his ex-wife killed.

Some privileges show themselves socially: men are typically taken more seriously than women, and seldom face danger, ridicule or real discrimination on the basis of their gender. The indigenous of Mexico are still presumed to be “backward” in many ways, and it remains an insult to call someone an indio.

(When I wanted to give my daughter the middle name “Xóchitl,” nearly everyone I knew made a face; they would swear it was because the name was just “so common,” but during my five years of teaching at an elite school I didn’t have a single student with that name. My guess is that it was only common for a certain unpopular sector of the population).

Though I’m not as rich as most Mexicans who look like me are, as a white woman in Mexico I easily recognize the privileges I receive; people notice and pay attention to me, wait on me attentively, and don’t question whether or not I belong in whatever fancy place I go to.

When the escalator at the grocery store stopped working today, a worker was immediately ordered to help the woman (me). Last week I walked up and confidently took a glass of wine off a table that had been set up for an event I was not participating in, confident I would not be questioned.

The LeBaron family killings were especially shocking because we collectively thought “not even those rich Americans are safe? My God!” We expect the privileges we have to protect us, and for the most part, they do.

With the level of impunity in Mexico at an all-time high — only one out of 10 homicides solved — it’s hard even to begin to think of ways to make this a more just society. But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, and I think President López Obrador, for all his faults, is making a good-faith effort to tackle the problem — particularly when it comes to making sure the especially economically privileged don’t keep getting away with what they’re used to getting away with.

Bills to reduce waste and kickbacks have been approved, as have measures to reduce the salaries of government officials and overall budgets.

It doesn’t feel good to lose extra benefits, and it doesn’t surprise me that there’s been so much push-back. But if we’re going to create a more equal and just society, we can’t allow certain people to make their long list of “endless” mistakes consequence-free while others are punished for essentially the same behavior.

We humans are very status-conscious creatures, and in a country like Mexico where most people prefer to avoid conflict and discomfort at all costs, the challenge of getting people either to stick up for themselves or stick up for the law is palpable.

Justice is personified as a blindfolded woman with scales in her hands. Why is she blindfolded? Because justice should be applied across the board, without regard for whom it is being given. We’ve got a long way to go before we get there, but at least we’ve started down the path.

Sarah DeVries writes from her home in Xalapa, Veracruz.