An inexpensive butane lighter can indicate the underground presence of invisible, odorless, carbon dioxide and can help cave visitors avoid death by asphyxiation.

Many years ago I had a chat with Dr. Merlin Tuttle, founder of Bat Conservation International. When I asked him about close calls underground, Tuttle cited a near-death experience in a Texas cave.

Near-death by CO2

Tuttle and a friend had worked their way down to the lowest part of the cave. Suddenly each of them simultaneously mentioned that he was finding it difficult to breathe and feeling extremely tired. Fortunately, this reminded Tuttle of an article he had read on the symptoms people experience just before they die from exposure to carbon dioxide.

Tuttle grabbed his companion and the two of them headed for the cave entrance, which they were barely able to reach in their weakened condition. They both collapsed outside the cave and were able to stand up only after several hours of breathing fresh air.

CO2 is invisible and odorless

Controversy surrounds the cause of carbon dioxide buildup underground. Both rotting vegetation and bats’ breath have been named as culprits, however, one thing is sure. Because it is completely invisible and completely odorless, an underground “lake” of carbon dioxide poses a mortal threat to anyone who walks or crawls into it. Carbon dioxide, in fact, has been called “the silent killer.”

Bad or foul air has been found in many caves and mines all over Mexico and, unfortunately, there is no easy way to predict where you might find it. If it is present, it is typically found at the lowest point of caves or pits with poor air circulation.

Symptoms of CO2 asphyxiation

Carbon dioxide is not poisonous, but it can kill simply by depriving air breathers of oxygen. The very first symptom a cave visitor will feel in its presence is faster breathing. If he or she is on the move, this accelerated breathing may not be noticed at all. The next symptom is tiredness, which may be the last thing the visitor remembers, because the third symptom, unconsciousness, follows very quickly.

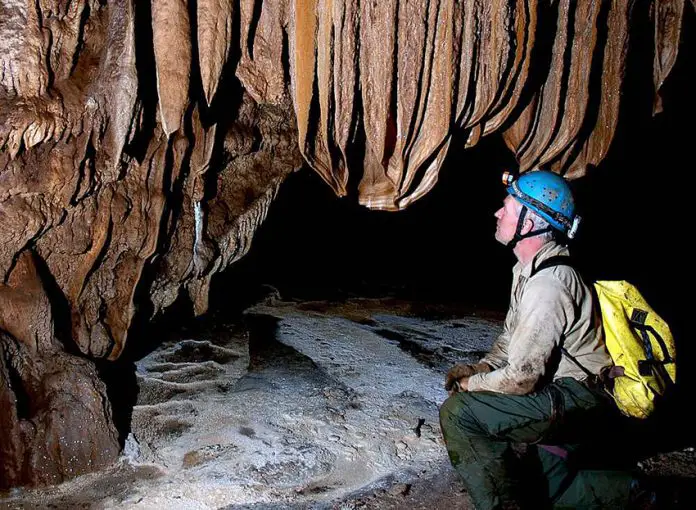

How does a cave explorer go about detecting an invisible enemy? One solution is to buy a costly oxygen meter. A far simpler and cheaper approach is to carry an inexpensive butane lighter or even a book of matches whenever entering a cave.

An ordinary butane lighter

Many cave explorers have been doing this since a 1989 report was published stating that these lighters cannot produce a flame if there is less than 17% oxygen present. Since people tend to black out with less than 17% oxygen, an inability to “flick one’s Bic” could indicate a deadly situation.

The report also mentions that a curious one-inch gap appears between the lighter and the flame when the oxygen level is 17.5%, an excellent indicator that it is time to turn tail and leave the cave. For many cavers, a butane lighter is part of the basic equipment they carry every time they venture underground.

Sunk in a pool of carbon dioxide

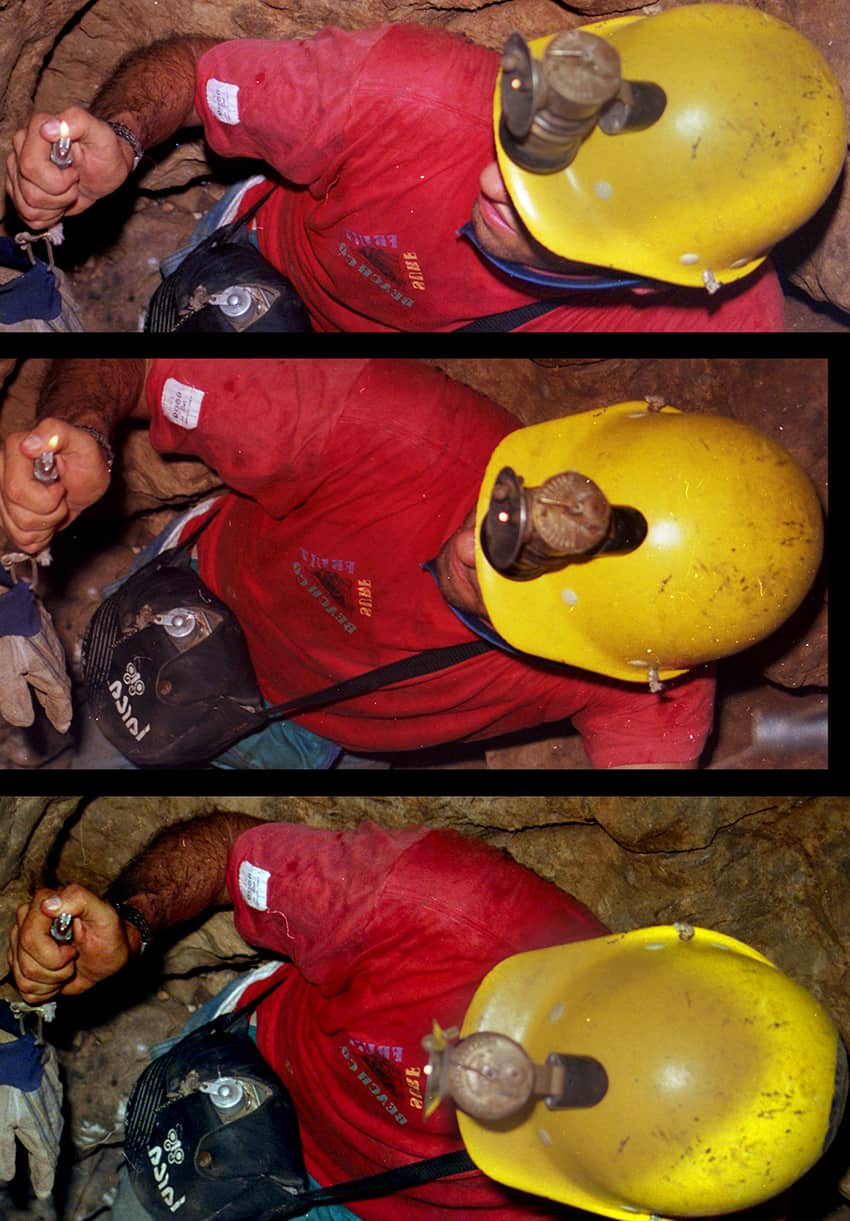

Ignorant of these facts, two cavers and I came upon the entrance to a deep pit in 1990 on a remote hilltop called Las Tierras Huecas (The Hollow Land), above Jalpa, Jalisco.

The pit entrance was about one meter in diameter. The rocks we dropped into it took eight seconds to reach the bottom, so we figured it must be very deep and lowered the entire length of our 150-meter-long rope into the pit.

I was privileged to make the first descent and all went well until suddenly my carbide lamp went out. These lamps, once popular for visiting mines and caves, provide light from a bright flame that burns acetylene gas.

As I neared the bottom of the pit, I found myself huffing and puffing.

“Why am I so tired today?” I wondered. “When I get to the bottom, I’m going to take a good rest.”

At the bottom, however, I was breathing even faster, and it was at that moment I remembered the words of Merlin Tuttle: that a person in a cave, breathing heavily, may be immersed in a lake of carbon dioxide and may have only one more minute to live.

I abandoned the idea of taking a rest, set a new speed record for connecting my mechanical ascenders to the rope, and started back up.

I was now huffing and puffing like a train, but just 10 meters up I hit “real air,” which I instantly recognized, just as if I had popped my head out of a swimming pool – and it tasted truly delicious!

Today, smart cave explorers include a butane lighter in their kit and you ought to as well, should you ever decide to wander into a cave or mine in Mexico.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.