The neighborhood public library occupies a warm spot in the memories of my childhood — a friendly, welcoming place, as well as a seemingly limitless source of information and entertainment.

When I moved to Mexico some decades ago, lending libraries open to the public were few to be seen. Sometimes I would find one in the Casa de Cultura of some pueblito, but most often their book collection would occupy only a couple of shelves.

A friend of mine with the United States Peace Corps noticed the same thing. Unlike me, she did something about it.

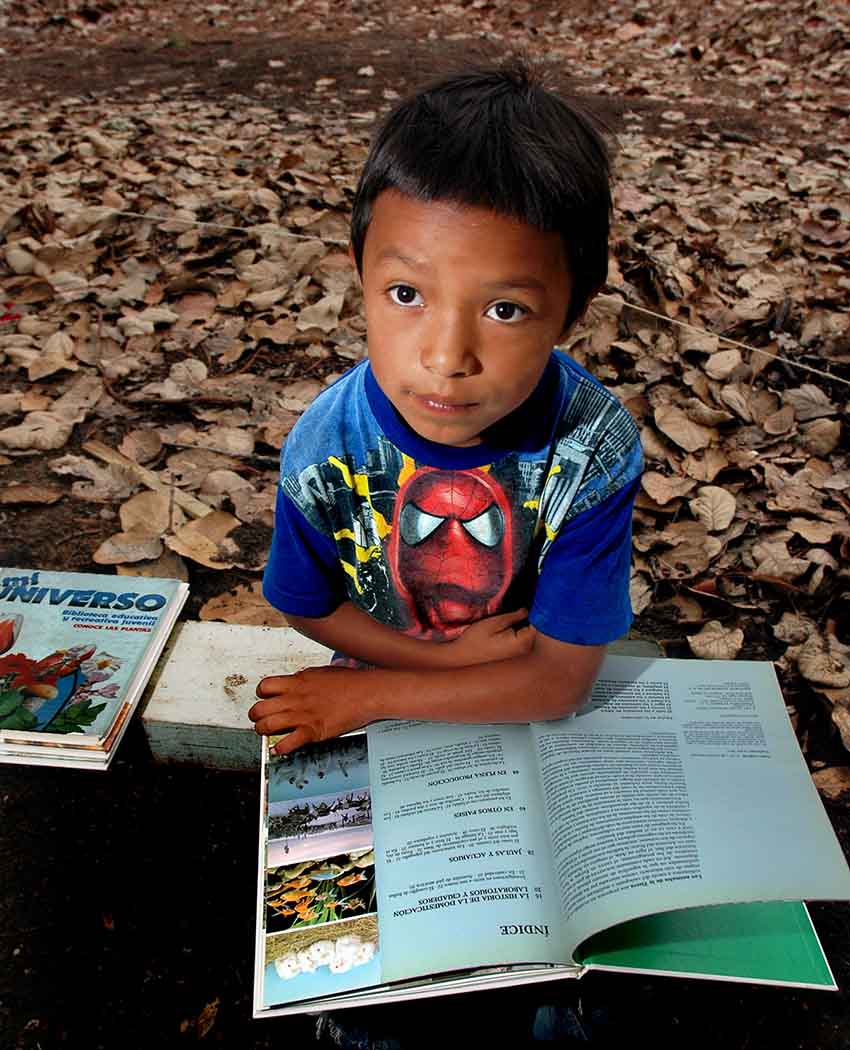

Barbara Dye found resources to buy children’s books and started her own traveling library, bringing reading material to kids in remote corners of Jalisco’s Primavera Forest. One day, I tagged along in her truck-turned-bookmobile.

I must confess that I was greatly moved by the joy and enthusiasm of those children as Barbara brought them new boxes of books from which they could choose ones to borrow. What impressed me most, however, was what the kids were doing with those books.

“They’ve started their own school,” Barbara told me, “under this tree. They meet together regularly, and each one tells the others all about the book that he or she is reading.”

The idea of a public library in Mexico, I suspect, may have been influenced by the notion of public libraries in Spain.

Once upon a time, in 1976, I lived in Barcelona. When I discovered that the Biblioteca de Catalunya had a huge collection of books, both in Spanish and in English, I made immediate inquiries about acquiring a library card.

I had wanted to do a comparative English-Spanish study of literary translations. I thought the Barcelona library ideal for this but quickly discovered that I could not accomplish my purpose without a library card.

To get one, I was obliged to amass a thick stack of documents, including a letter from the United States consul swearing that he would take personal responsibility for any books I might fail to return. It took four months till I finally had that precious library card in my hand.

My wife and I walked into the Biblioteca. I was carrying a camera and tripod (knowing that in Spain, flashes are an abomination in all public buildings). I hoped to get pictures of some of the library’s impressive murals.

Out of nowhere, a guard popped up. “Señor, we do not permit the use of cameras — or tripods — in the Barcelona library.”

So I checked the tripod and camera and we walked — hand in hand — toward the room housing the English book collection.

Another guard appeared out of nowhere.

“Estimados visitantes,” he said, “I regret to inform you that holding hands between persons of different genders is forbidden in the Barcelona library.”

Blushing, we distanced ourselves from each other, and I found a copy of The Old Man and the Sea. “Now, we’ll just go look at the Spanish version,” I said.

But before I could take two steps, a third guard appeared, as if right out of the woodwork.

“¡Por favor!” he said. “You may not remove any book from any room in —”

I finished the phrase for him: “in the blessed Barcelona Library. But don’t worry, señor. I have a feeling that this is not only my first but also my last visit.”

And, in fact, it was.

By chance, I now live only 29 minutes away from the Jalisco state library. Several visits have proven to me that it is far friendlier than the one I encountered in Barcelona. Perhaps this is due to its whimsical design.

If you get a chance, take a look at it and ask yourself: inside a building like that, would anyone be worried about people holding hands?

La Biblioteca Pública del Estado de Jalisco “Juan José Arreola” is located at the extreme northwest end of Guadalajara, just along the city’s ring road, the Periférico. This location has caused many city residents to be familiar with the building’s unusual and controversial architecture, designed by González Gortázar Architects.

Counting its newspapers and magazines, this library — administered by the University of Guadalajara (UDG) — holds over two million items, surpassed only by the library of the National Autonomous University in Mexico City.

But can you go there and actually borrow a book?

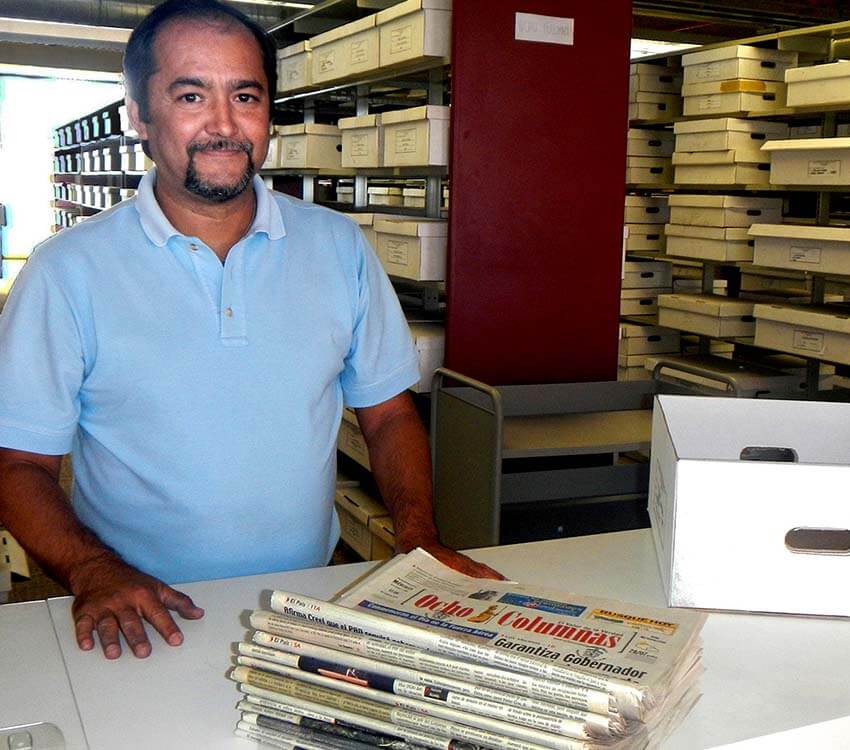

To find out, I went there and put my question to library representative Rigoberto Hernández Gómez.

“I’ll tell you the truth,” Hernández confided. “We tried lending books 20 years ago. To make sure that all the books would be returned, we obliged people to leave their official ID card with us. The result was that we ended up with no books and three huge boxes of ID cards!”

Although you can’t borrow books from this library, you can read them onsite, with many options to choose from. To start with, the Biblioteca is divided into two buildings, one filled with contemporary works and the other dedicated to venerable old historical documents that you must view wearing gloves and a face mask.

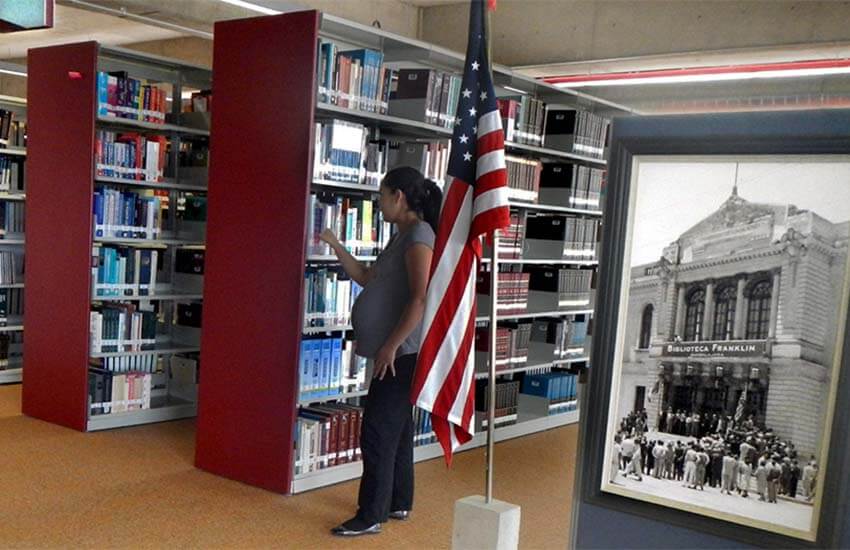

The first building, the Edificio Contemporáneo, was full of surprises. For example, on the fifth floor, I discovered the Benjamin Franklin Library, donated by the U.S. Consulate and chock full of great books in English.

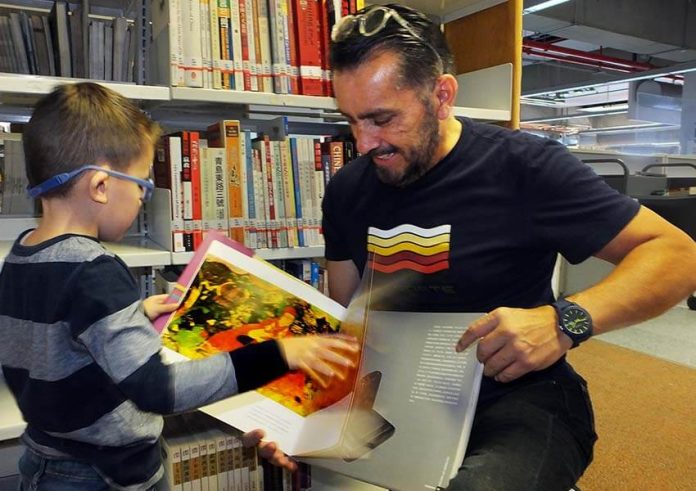

Next to it is another huge collection of 50,000 books, all in French (the Paul Rivet Library). On the same floor, there is a big collection of books in Catalan and another one of books from China.

“This collection,” Hernández told me, “is the result of a book exchange between the Chinese government and the UDG. Each donated 626 books to the other with the idea that in the future they would continue making donations. And both collections have grown considerably.”

I also discovered a big collection of books for children and adults in indigenous languages.

“Mexico’s indigenous population speaks 68 different tongues, and there are 364 varieties,” librarian Nilva Ordón told me. As an example, she showed me a book in Hñähñu (Otomi), a language spoken in several Mexican states. “Hñähñu has 14 vowel sounds, as opposed to five in Spanish,” she mentioned.

Since I am a language teacher, I countered that English has between 19 and 21 vowel sounds — depending on which expert you talk to — and assured her that for most Mexico News Daily readers, Hñähñu would be a snap.

According to Hernández, the newest addition to the Jalisco State Library is the Centro Documental de Literatura Iberoamericana Carmen Balcells (The Carmen Balcells Documentary Center for Ibero-American Literature). This is a complete collection of great works of literature produced in all of Latin America, including Brazil.

It’s unique because Carmen Balcells, who is from Spain, insisted that proper royalties be paid to all the authors of all these books: a position that stands in sharp contrast to the exploitation of writers frequently practiced in some Latin American countries.

In addition to everything I’ve mentioned above, there is also a very big librería (bookstore) inside the library: the Librería Carlos Fuentes, which boasts 120,000 titles.

So, while the library will not allow you take a book home, the librería will not object at all … as long as you pay for it.

The Jalisco State Library doesn’t quite have the nostalgia of the neighborhood public libraries of my youth, but, of course, they — and I — are from another millennium.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.