A small mound of clay sits on the table just to Jorge Casbal’s right. He tears off a small chunk and deftly shapes a piece that’s a little larger than a half a tennis ball; this is the base of what will become an árbol de la vida — a tree of life.

He takes another piece of clay and gently rolls it between his hands, forming the central tube, and lays it on the table in front of him. He repeats this several times as he makes the various parts, his hands moving confidently. Nothing is measured, and everything is done by hand.

He knows what he needs to do from years of experience, and he makes it look easy; but it’s not.

“To make the most basic thing, [a person] can learn in about six months, practicing every day,” he said. “It would take about a year in training to make a small árbol de la vida.”

Jorge and his brother Ulises are the owners of Arte Casbal in Izúcar de Matamoros, Puebla, which is famous for its barro policromado — painted clay — and especially its árboles de la vida.

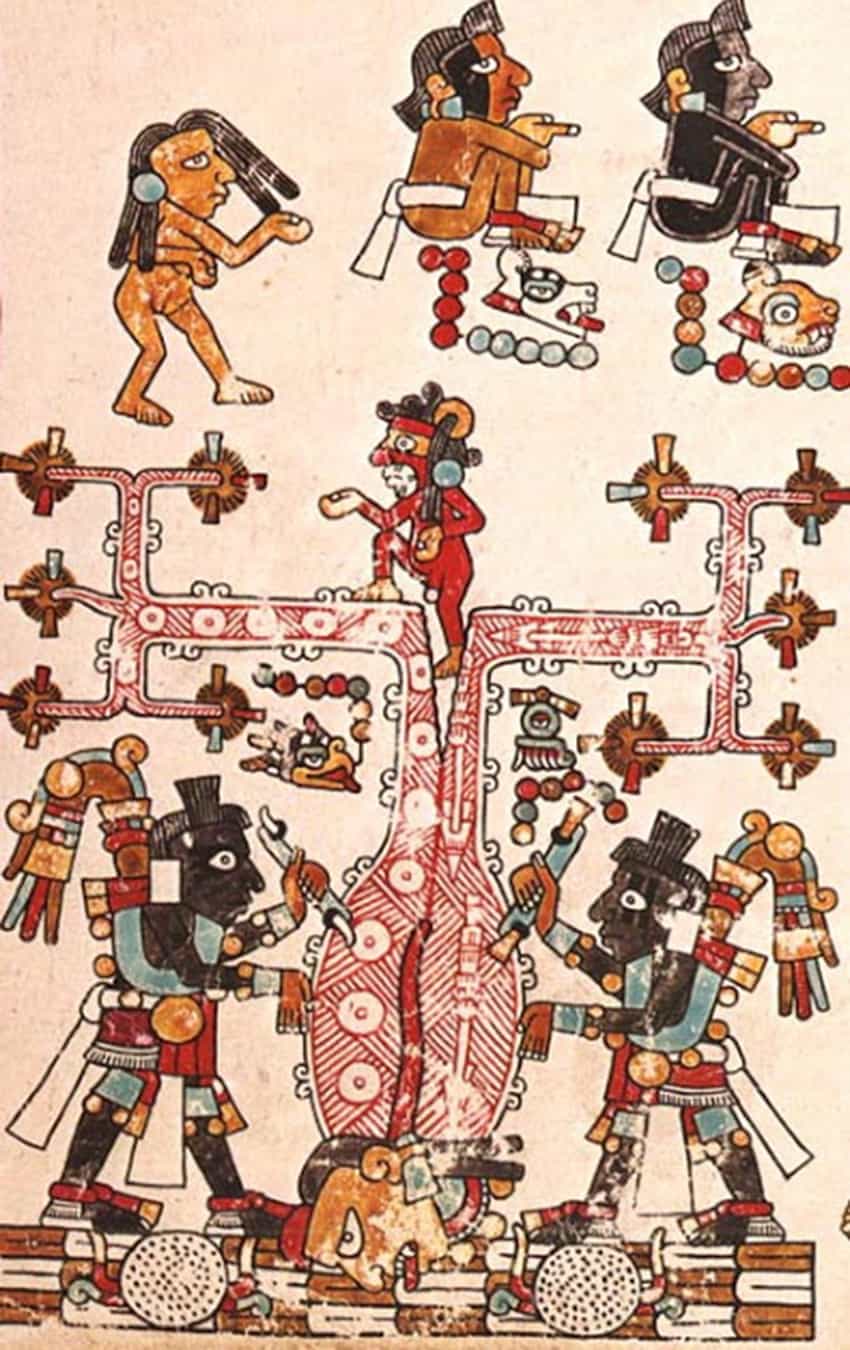

The earliest discovered depiction of a Mexican árbol de la vida is found in the Codex Vindobonensis, a Mixtec parchment believed to have been made a few decades before the arrival of the Spanish in 1519. The Mixtecs occupied an area that is now Oaxaca, Guererro and Puebla.

“In the codex, there is a tree called apoala,” said Jorge, “and it represents the beginning of life, according to the Mixtec culture.” The tree also shows the origin of the Mixtec ruling families and the civilization’s early history.

Mexican indigenous groups have been using clay to make figures and other items for thousands of years. In the country’s central region, unpainted clay figures date from around 1800 BC.

Painted figures appeared much later, first in the Olmec culture. Still later, around AD 800 in Teotihuacán, figures with religious symbols began to appear.

It’s not clear when the first clay árbol de la vida appeared in Mexico, but the ones that we’re familiar with today — ones that incorporate images and symbols based on Catholic religious icons — appeared after the Conquest. Like many things in Mexico, this indigenous art form has changed over the centuries.

“With the arrival of the Spanish and evangelization, the árbol de la vida was transformed,” Jorge said. “The Moors invaded Spain, and from there, the Spanish brought Moorish images here, and we use them in our polichromado. Our pieces are a mix of three cultures: Spanish, Moorish and Mixtec, but [the] Mixtec also have an Olmec and Zapotec influence.”

Making árboles de la vida and other figures is a family tradition for Jorge and Ulises that goes back generations. “During the Revolution, the art was being lost, and it was recovered by my grandmother, Catalina Orta, together with Don Aurelio Flores,” said Jorge.

His grandmother taught all her children, including Jorge and Ulises’ father. Unfortunately, their father eventually lost his studio and abandoned the family, but fortunately, he’d taught his wife, Maria Luisa Balbuena Palacios, who is now recognized as a master of the craft. She in turn taught Jorge and Ulises.

The family struggled after their father left. “We lived in extreme poverty,” said Jorge. “Sometimes we had nothing to eat. We went to school, but we were not good students. But little by little, we came to love crafts.”

In 2003, the brothers convinced their mother to let them enter a piece in a competition sponsored by the National Fund for the Development of Handcrafts (Fonart). “Despite being first-timers, we took second place, and that started to change our history,” Jorge said.

Soon afterward, they decided to start their own studio.

“My mother is very traditional, and we made variants,” Jorge explained. “Also, we wanted our own workshop, our own style, and because of this, we wanted our independence. And so we formed Arte Casbal in 2004.”

Before they can start making one of the tree figures, the clay must be prepared over weeks. It starts out essentially as a stone that they first pound and grind and then sift to remove any small stones and other impurities.

The resulting powder is put in a tank of water for a week or two. The water is then removed, leaving behind something that Jorge described as being like a “mole paste” — which the brothers then knead. After all that, the clay’s ready to be sculpted.

Jorge takes all the pieces that are laid out in front of him and gently connects them. He smooths out the spots where the pieces are joined and places the unfinished árbol de la vida upright. He’ll leave it on a shelf to dry for three or four days before placing it in an oven. The hot air in the oven can crush them.

“Once dry, we put them in an oven at C 800, using something traditional: firewood,” he said. “This is a very long process, and it is a process done absolutely by hand.”

Traditionally, an árbol de la vida has an image of God on top, as well as Adam and Eve figures and a serpent, although some have strictly secular themes such as animals and nature. In the brothers’ studio, the decorations typically incorporate indigenous designs and symbols.

The sculpture is customarily given to newlyweds “as a symbol that they are wishing the couple a family union that’s prosperous,” said Ulises. “One with many children.”

A small, eight-inch item, like the one Jorge was working on, takes about a week of continuous work to make and costs 1,500 pesos (US $75). At the time of my visit, an assistant was painting a very large, elaborate one that Jorge estimated took 20 days to make and will take another 20 to paint. That one cost 40,000 pesos (nearly US $2,000).

They also sell a variety of other figures, including ones for Day of the Dead.

There were once many more workshops like Arte Casbal in Izúcar de Matamoros. “Now there are 12 family workshops,” said Ulises, “maybe two others.”

The brothers realized that the craft was being lost and began doing what they could to preserve it. “My brother and I undertook to start social networks [promoting the craft],” Ulises continued. “We promote it in fairs.” They also train people.

Still, they and others in their family struggle to keep the knowledge alive and to survive. When asked if they can continue their work, Jorge wasn’t optimistic.

“It depends,” he admitted. “We do it for love, and we will continue. Once, someone asked my cousin if he will continue this work, and he said no. The person asked why. My cousin said, ‘So my children do not die of hunger.’”

• You can view and purchase the brothers’ work at their website or on Facebook and Instagram.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.