When she was 20, Canadian Shari Bondy, who worked on various boats in the Pacific, found her watercraft blown out to sea by a storm in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, off the coast of Oaxaca. At some point, she fell unconscious, came to, and found that the vessel was surrounded by whales, who were keeping the boat from flipping over.

She thinks she might have had a near-death experience or something similar because her memories of the event include the whales somehow “talking” to her, telling her that she would be OK and — when she realized she was safe and wanted to somehow thank them — urging her to tell people about them.

She later found out that it was not rare for whales to come to the aid of unlucky humans at sea. So back in Canada, she began studying whale behavior and working on tours that took people to view gray whales on the northern end of their migration route off British Columbia.

But to understand the whales meant to also know the southern end of that migration route — in Baja.

During Bondy’s first visit to Baja California Sur in 1988, she heard about a then-unknown lagoon in Mulegé where whales were so comfortable with humans that they regularly interacted with them, even bringing their babies along. She decided to check it out.

What was supposed to be an hours-long visit to Ojo de Liebre in Mulegé, also known as Scammon’s Lagoon, turned into weeks. It changed her life.

She became pregnant there with her daughter, but that is certainly not the only way the trip profoundly affected her. The experience with the whales in Ojo de Liebre floored her, and she knew she needed to study them.

But finding a way to live here and finance her research wasn’t easy. For some time, she literally lived in a tent on the beach with her daughter and teamed up with local fishermen to give whale sighting tours in English for tips.

She says she was “flying under the radar” since she didn’t know that she needed a permit to do this.

The years went by, and after about a decade, one tour guest happened to ask her what her company’s name was.

She had never thought about it. It was just an informal thing she’d worked out with local fishermen, and most of what she got out of it was the chance take pictures and do other whale research activities.

This guest suggested that she formalize the tour business and asked her, “What is it? What is it that you do?”

Her answer was, “It’s not really what I do; it’s what the whales do. They do this whale magic.”

Hence the name she finally gave her business: Whale Magic Tours.

The tour company is based in that same lagoon that captivated her so many years ago, but today she works with her now grown-up daughter, Sirena. Both are bilingual guides who have lived with and studied the whales for decades.

Unlike other tour operators, they are able to educate visitors from all over the world about whale behavior and biology, the history of the lagoon and stories of the human and whale encounters they have witnessed. Bondy says that gazing into the eye of a whale is a “humbling, life-changing encounter you will never forget.”

At the peak of the whale sighting season here, which runs from January to March, there can be up to 2,000 mothers and babies in the lagoon.

So why do the whales approach people?

One reason is that there has been no hunting here in living memory, so the whales feel safe.

The other reason is that the whales here are kind of bored.

While in Baja, they are entirely focused on bearing their young and preparing them for the migration north. They are not even eating. So the gaggles of humans coming out to see them is a kind of entertainment.

They come close and like to be caressed by people’s hands. It is definitely a learned behavior, as it happens nowhere else in the world.

In the 1970s, Mexico began implementing the whale protection measures in the lagoon that are currently in place. The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve was established in Mulegé in 1988.

Mexican authorities asked Bondy to help establish rules for the growing number of humans going out to see the whales in the lagoon.

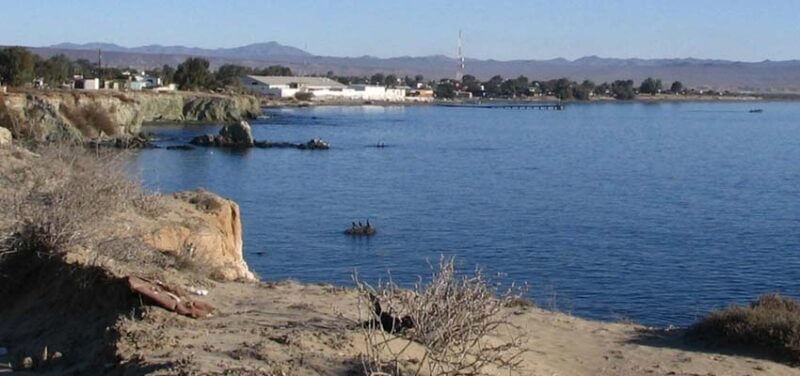

But Bondy’s involvement in the development of this part of Baja has not ended there. Some years after settling in Mexico, she met and married a fisherman from the little-known town of Bahia Asunción, Mulegé, south of the whale lagoon.

The couple settled into a small house there in 2002 when it had no paved roads, no electricity and no running water. Despite that, they began receiving guests in 2006 and slowly expanded into a bed and breakfast.

It eventually became a hotel called La Bufadora, named for a nearby natural blowhole.

The two businesses keep the Bondy family busy, but Shari still wants to do more for this part of Baja. It attracts a certain kind of tourist, those looking for something off the beaten path or something more laid-back than the popular tourist destinations of Los Cabos and Ensenada.

Despite its growing fame due to the whales, the town of Bahia Asunción is still not terribly developed because even with a paved road, it is an hour from the main highway. “People are too busy to make the detour and check it out,” Bondy says.

But it’s worth the trip for the miles of pristine beaches, fishing, boat trips to Asunción Island and, of course, fresh seafood, she adds.

Although the season for tours starts in January, Bondy suggests making arrangements now as spaces fill up quickly, especially with limited space due to COVID-19 rules.

• To book a tour with Whale Magic Tours, you can contact them at whalemagictours@gmail.com.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.