For years, Mexico City artist Victor Cruz García has been popping up all over social media as “The Cave Painter.” One can find pictures of him online hanging in the air with the greatest of ease, wielding his paintbrush while dangling from a rope deep inside the bowels of the earth.

This year, Cruz marks a decade and a half of wedding art and speleology. When I got a chance to talk to him, I had to find out how he started this unique pastime.

“Why do you do it and how do you do it?” I asked him.

According to Cruz, he owes his unusual career to his older brother, Claudio.

“When I was a kid, Claudio was doing rock climbing and was kind enough to let me tag along,” Cruz said. “Later, he got interested in caving and joined a cave rescue group called URION.”

In 2007, when URION was organizing a speleological conference in the town of Cuetzalan, Puebla, Claudio asked Victor to design a poster for the event.

“So I made the poster, and then they had a big meeting of all the people who were promoting this conference, and they said, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if there could be an exhibit of paintings showing some of the beautiful caves we have here in Mexico? Who knows if anything like that has ever been done before?’”

At that point, Cruz didn’t know a thing about caves, but he did love art, having been inspired by the award-winning landscapes of José María Velasco and by the paintings of Guadalajara artist, writer and volcanologist Dr. Atl.

With an aim to continue both artists’ tradition of presenting Mexico’s natural beauty to the world, Cruz went to study at Mexico City’s School of Design, Art and Publicity.

“I don’t know anything about caves,” he told the organizers of the Cuetzalan speleological conference, “but if you have photographs, I’d be happy to try turning them into paintings.”

The organizers had photos, all right, but they were not quite the kind Cruz expected.

“What they brought me were all 35-millimeter slides but without any sort of projector. So there I was, standing in front of my easel, holding these postage-stamp-sized slides up in the air, squinting at them through one eye while looking at my canvas with the other.

“And that’s how I did my very first paintings of caves: a whole collection called Pinturas de Cuevas de México.”

Cruz attended all the sessions at the Cuetzalan caving conference, but, he says, “I noticed that practically all the presentations were being made by foreigners, and I asked myself, ‘What about the Mexicans? Where is their work?’

“And that’s when I realized that my exhibit of paintings was it — the Mexican contribution!”

Two years later, in 2009, the 15th International Conference of Speleology was held in Kerrville, Texas, and the Mexican cavers decided to present their show of cave paintings to the worldwide community of caving aficionados.

“The cavers definitely enjoyed my exhibit,” Cruz told me. “I know for sure because they would come up to me and say they would really like to have this or that painting, and I would say, ‘OK, I’ll sell it to you.’ But I soon discovered that all over the world, including the U.S., cavers tend not to have a whole lot of money.”

So he made trades with these cavers for gear and ended up acquiring all his caving equipment that way.

Soon, Cruz began to explore caves in earnest. He even participated in cave rescues such as that of Arthur Meauxsoone, a Belgian caver who in 2008 broke both legs 400 meters below the surface inside a difficult Puebla cave. Cruz and the other Mexican rescuers slowly but safely brought Meauxsoone back up to ground level.

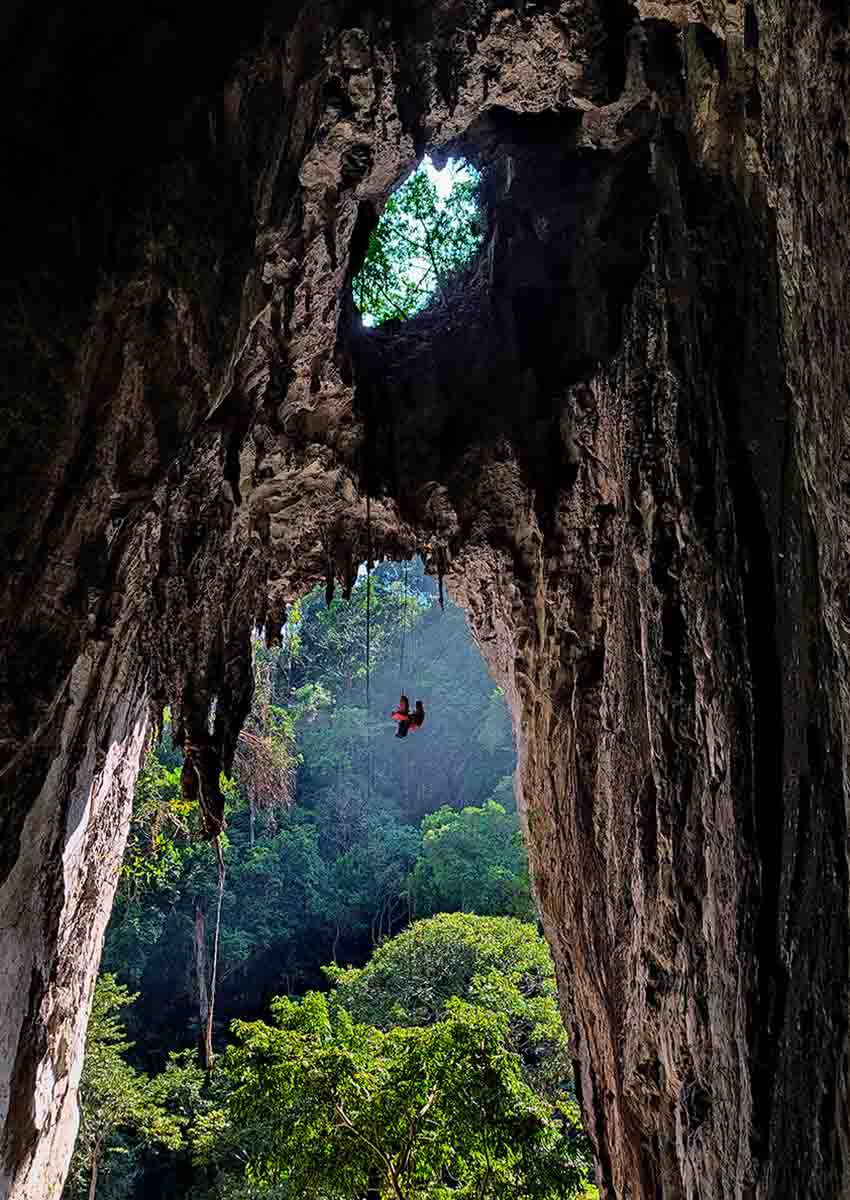

“It was sometime after that rescue that friends invited me to a famous cave in Zongolica, Veracruz, called el Sótano de Popocatl, which means “the Pit of the Smoking Water,’ Cruz said. “The entrance is a big vertical drop 45 meters wide, and into it pours a gorgeous waterfall to a depth of 70 meters.”

Cruz felt it was a place everyone should see.

“So when I had my first chance to go back there, I told my brother, ‘I want to paint that waterfall, but I have to do it suspended in the air, in the middle of the entrance pit.’ And all the other cavers said, ‘Claro que sí, we will help you work out how to do it.’ And all together, we designed something I call my speleo easel.”

While Cruz succeeded in painting the Popocatl waterfall from the end of a rope, it wasn’t without problems.

“Everything was moving!” he said. “I was like a piñata, swinging back and forth, in and out of the spray from the waterfall, and all the paint on my canvas was running!”

In time, he learned how to stabilize himself in midair and to design a lightweight easel with a kind of drawer to hold paints, rags and even a fruit snack. It had special holders where the brushes fit snugly. These days, he also has a comfortable seat that holds his weight while painting.

Cruz uses acrylics and paints on a canvas measuring 50 centimeters by 60 or 70 centimeters. He started out using three ropes to hold himself and his gear but now needs only two.

Cruz soon discovered that painting en pleine caverne was not exactly like en plein air.

“A big lesson I learned was that my canvas would look like one thing inside the cave, lit by my headlamp, but when I took it out in the daylight, the colors might look completely different!” he said.

“It’s like what cave vandals discover: the stalactite that looks unbelievably beautiful in the cave doesn’t look the same once it’s been snapped off and carried away. Outside the cave, it looks dead. So I would have to retouch my paintings once I looked at them back home.”

Could he possibly take painting in a cave to yet another level? Cruz tinkered with the idea.

“Mexican cenotes are filled with water,” he said, “which led me to think about painting underwater.”

Cruz investigated the work and techniques of Denis Lotarev, a Russian artist who paints while diving in the Red and Black Seas.

“I decided to give it a try, not in Yucatán but at the bottom of an incredible water-filled pit they have in Nuevo León called El Pozo Gavilán. There I discovered that the techniques of our compañero Denis work quite well … but it’s pretty tricky, perhaps even more challenging than painting while hanging from a rope.”

“With all this,” says Cruz, “I hope I can inspire the new generation to believe in their projects, not to be afraid of criticism but to consider everything as part of the learning process. If you never try, you’re a loser for sure, but if you do try, you just might succeed!”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.