I’ve kissed thousands of cheeks since I moved to Mexico 13 years ago. I’ve also had more than one disaster.

Working in a small, rural community outside San Miguel de Allende, I once watched a weathered farmer eye me with horror as I went in for it. I’ve brushed lips with strangers and colleagues alike in blundered attempts to hug and not kiss, or kiss and not hug.

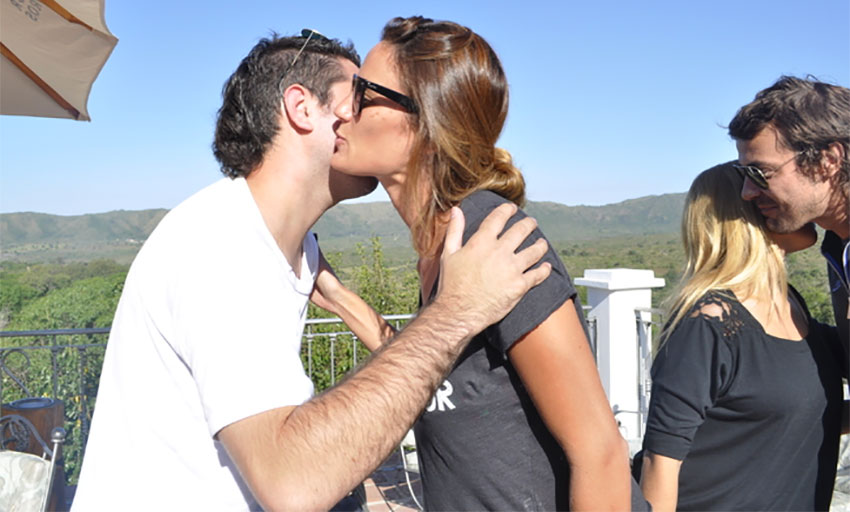

More than once a little extra lip pressure from an attractive friend of a friend at the bar made my inebriated mind run wild with visions of our future passion.

And the obligation of it all! Everyone in the room has to be kissed hello and kissed goodbye. It’s often made me wish that I could just scrap the cheek kiss altogether. Despite my love for Mexico City’s touchy-feely freedom — metro make-outs, spontaneous dirty dancing, park bench snuggling — the cheek kiss has never been something I waxed nostalgic about.

But recently, the enforced social distancing put in place to deal with the Covid virus has elicited a strange response in my body. Upon seeing people I know I find I take an instinctive lunge forward, my hands starting to rise to mid-bicep, my head inclining forward, lips poised for a brush on the cheek.

I stop myself, as the responsibly paranoid citizen I’ve become in the past five months, but an odd feeling lingers. Something unsaid, something undone. Conversations have no beginning and no end, deep within I’m uncomfortable, itchy. After almost a decade and a half this particular habit has become so ingrained in my social interactions that my body responds without guidance; I guess you’d call it natural.

They say that the cheek kiss started with the Romans, a passionate bunch that not surprisingly spread the salutation wherever they went. While it might seem like a perfunctory gesture, search the internet and you will find hundreds of articles named things like “To Kiss or not to Kiss,” with charts explaining each kissing country’s specific kissing parameters.

There have been entire books written on the history, meaning, and tradition of the cheek kiss. Its appropriate delivery can make or break first dates and business deals. The 14th-century plague reportedly put a pause on kissing for a while, but it came back with a vengeance after the First World War and has been going strong since. So while U.S. writers are ready to dig the handshake’s grave, I ask myself, is it really possible that the cheek kiss will be so easily banished?

The fear of losing this and other intimacies is very much alive in my neighborhood. Every Saturday in front of my apartment in Mexico City the local soccer team drinks themselves happy at the convenience store. Handfuls of guys in gym shorts and long socks sip beers, make jokes, and even sing opera from time to time. I can hear the timbre of their laughter and the thud of palms against backs from my upstairs window.

I admit I don’t always share the joy of their weekly sidewalk party, but most of the time their presence is soothing. People are on the street, life is happening. These past Saturdays have been silent, the taco stand next door that houses half of the group at a time has been closed for months. Many are likely kept home by wise wives. Their missing presence in the soundscape feels ominous.

That goes for the coffee shop kids too, who a few storefronts down huddle around cold brews and Japanese siphons, telling high-decibel stories to hide the insecurity of their gangly bodies and over-caffeinated hands. They are gone too, replaced by a single nerdy barista serving coffee to go from behind a wooden barrier. The street that used to be so lively is as quiet as a three-day weekend.

In Mexico life is lived in the street. As one friend puts it, “we were taught to live outside, not inside.” And the country’s publicness – kissing in the park, eating on the street, and sitting down beside a neighbor to share a smoke or gossip – doesn’t exactly fit with the new restrictions in our lives. How does a city of more than 28 million people socially distance from one another? Do we even want to?

Life on the street keeps you informed about what is happening, who’s sick, who has a new baby. Plenty of the neighbors don’t even know each other’s names but we recognize each other by face, and now even that is harder to do. “I don’t want to live in a world where I can’t see people smile,” one of my neighbors tells me on a recent morning.

Mexico’s president got a lot of negative press at the beginning of the pandemic for hugging and kissing his supporters at public events. He said he wanted to put them at ease, let them know that everything was fine, but honestly, I think maybe he just couldn’t help himself. Our everyday norms are just powerful.

So while we’ve nothing to do but move forward, with our ghost gestures, like ghost limbs, haunting us in conversations, we wonder will the little intimacies of our lives return once the pandemic has passed? Or will we know them simply as things from the time before?

I think we are all envisioning a day when we will be able look at each other without cloth barriers, and astonishingly enough, I’m even hoping for a return of the cheek kiss.

Lydia Carey is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.