As anyone who has visited or lived in Mexico knows, Mexicans tend to be a little — well, let’s say imprecise when it comes to time.

When someone tells you when they’ll meet you or when something will start, take the time given as a fairly broad approximation. If you’re lucky, it’ll take place within an hour of the advertised time.

If you’re unlucky, as I’ve been on any number of occasions, it will be more like a couple of hours. No explanation is usually ever given, and I’ve never had anyone apologize for being late. The most I’ve ever gotten is a small smile and a shrug. It’s just the way things are in Mexico.

But in addition to imprecision, there are certain words pertaining to time that can lead to misunderstandings for the non-Mexican. I hope the explanations below will clear up some confusion.

Ratito

First, let me make it immediately clear that “ratito” doesn’t mean “little rat.” That would be ratita. I don’t want any unnecessary confusion because, when it comes to time, there’s confusion enough in Mexico.

I first heard ratito on an early trip here. Back then, as far as I could tell, it meant “in a little while.” So if I asked someone, “When are we leaving?” and they answered, “En un ratito” it meant we would be leaving in a little while — or what the person believed qualified as a little while.

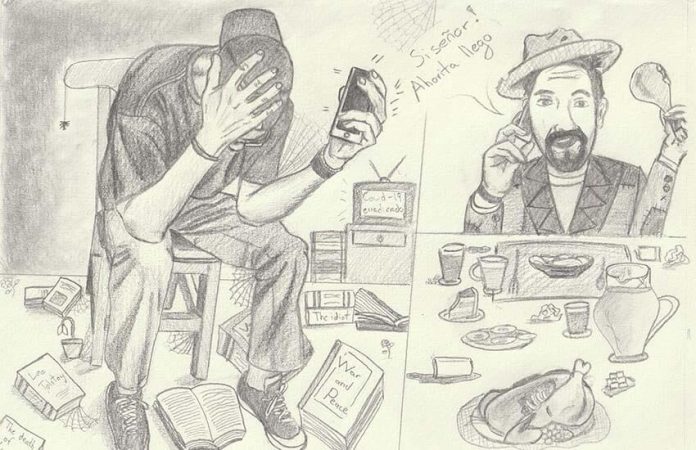

This has been as short as 15 minutes, but they’re typically longer — a lot longer. I’ve learned to bring something to read whenever I have a meeting in Mexico; Russian novels are best.

The longest wait I’ve had after hearing en un ratito was in the small pueblo of Las Margaritas, Chiapas. I showed up on time at a park to meet a contact for a project I was doing and waited; then I waited some more.

After about 30 minutes, I called the person and was told “en un ratito.” I think I called every 30 minutes or so and was told the same thing. The person finally showed up three hours later.

Hoy

Hoy means “today.” Pretty straightforward, right? And it is, except that when someone tells me that something is going to happen hoy or they invite me to do something hoy, I like to know when exactly (or, being in Mexico, approximately).

Many a time has a friend has invited me to dinner hoy. I want to narrow it down a bit, so I’ll ask, “When?” Nine times out of 10, the answer is a simple “hoy.”

Call me silly, but if we’re talking about an invitation to dinner, an approximate time’s greatly appreciated. But if I ask, “What time?” The answer is almost always, “Whatever time you want.”

I remember telling a friend I’d stop by at 6 p.m. and being told that was fine. Sure enough, I show up on time to find I’m about two hours early. Dinner prep hadn’t even started.

Mediodía

This is another one of my favorites because it’s so ambiguous. Technically, it means “midday” which, for me, means noon. Not necessarily so in Mexico.

I’ve been told many times that something is going to happen at mediodía, and it can mean from noon to sometime in the afternoon. Or evening. It’s never clear, and pressing someone for an exact time usually results in a look of confusion and a one-word answer: mediodía.

After that, I suggest they give me a specific time and sometimes get an answer. I’ll then show up, a Russian novel stashed in my backpack.

Ahorita

I don’t know if ahorita has evolved to mean a few different things since I first heard it or if I didn’t initially know that it means a few different things. It’s derived from ahora, which means “now.”

When I first heard ahorita, it meant “right now,” as in, “We are leaving ahorita — which, like ratito, could mean pretty much anything from “immediately” to “sometime today.” But, as I’ve learned, it has more than one meaning.

For example, I’ve been with Mexican friends at fiestas and watched as they’re offered something to eat or drink. If they answer, ahorita, it could mean, “Yes, I’d like some of that right now.” It could also mean they’d like some of that in a little while. Or, when accompanied by a raised hand along with ahorita, it apparently means “no.”

So, if you offer someone something to eat or drink and they say, ahorita, it’s probably best to get clarification. Which, of course, you may or may not get. But, hey, it’s worth a shot.

Mañana

OK, sure. Everyone knows that mañana means “tomorrow.” The confusion comes when a Mexican friend invites you to do something mañana. A typical conversation will go like this:

“Want to have dinner with me mañana?”

“Sure. When?”

“Mañana.”

“When mañana?

“Pues [well], mañana.”

This could go on for several minutes without any clarification.

What I’ve finally learned when invited to do something mañana is to ask, “What time tomorrow?” That generally elicits a more precise response, but if the answer continues to be mañana I ask no further questions and just show up sometime in the afternoon with Tolstoy.

Where I’m from, the United States, it’s considered rude if someone shows up late. Events tend to start on time there, and it’s what I was accustomed to. In general, that’s not the way it is in Mexico. I do have Mexican friends — and a Mexican girlfriend — who do show up on time. But those are exceptions to the rule. The best thing to do when you’re here is to be flexible and, most importantly, understanding.

So, I’ll admit that, at first, it bothered me a lot when I’d show up on time for a meeting only to twiddle my thumbs for half an hour or more. But I’ve come to accept the fact that I’m in a different country and culture and that I’m the one who must make adjustments. I don’t get upset anymore when someone’s late. Life’s too short to be bothered by such things.

I’ve developed a lot more patience — and a great appreciation for Russian novels.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.