La Catrina, the grinning skeleton with the elegant, floppy chapeau is, without a doubt, the most famous creation of Mexican cartoonist, illustrator, artist and satirist, José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913), whose work was so prolific that even today, no one knows exactly how many obras (works) he produced.

But if you’d like an overview of his work — and at the same time an insight into life in Mexico during the tumultuous days of the Revolution — the place you should not fail to visit is the José Guadalupe Posada Museum in Aguascalientes.

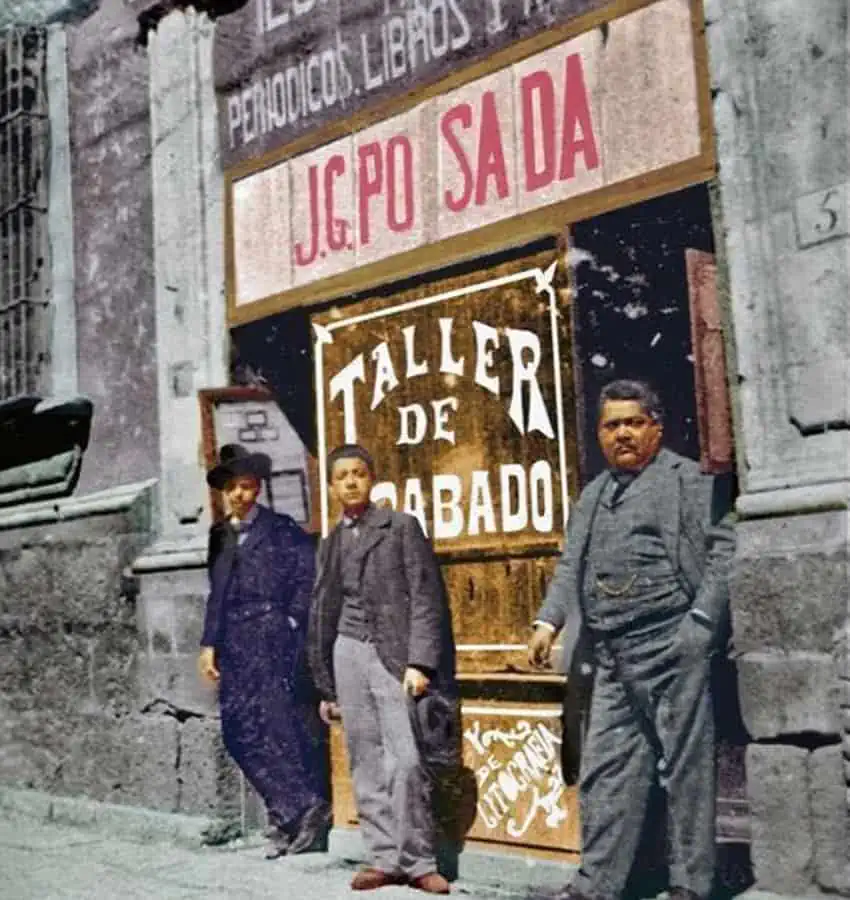

Posada was born in the city of Aguascalientes and began his career as a teenage cartoonist for a local newspaper. Unfortunately, the paper was forced to close after 11 issues, supposedly because one of Posada’s cartoons had offended a powerful local politician. He then moved to León, Guanajuato, where he started a printing shop that flourished until 1888, when a disastrous flood hit the city.

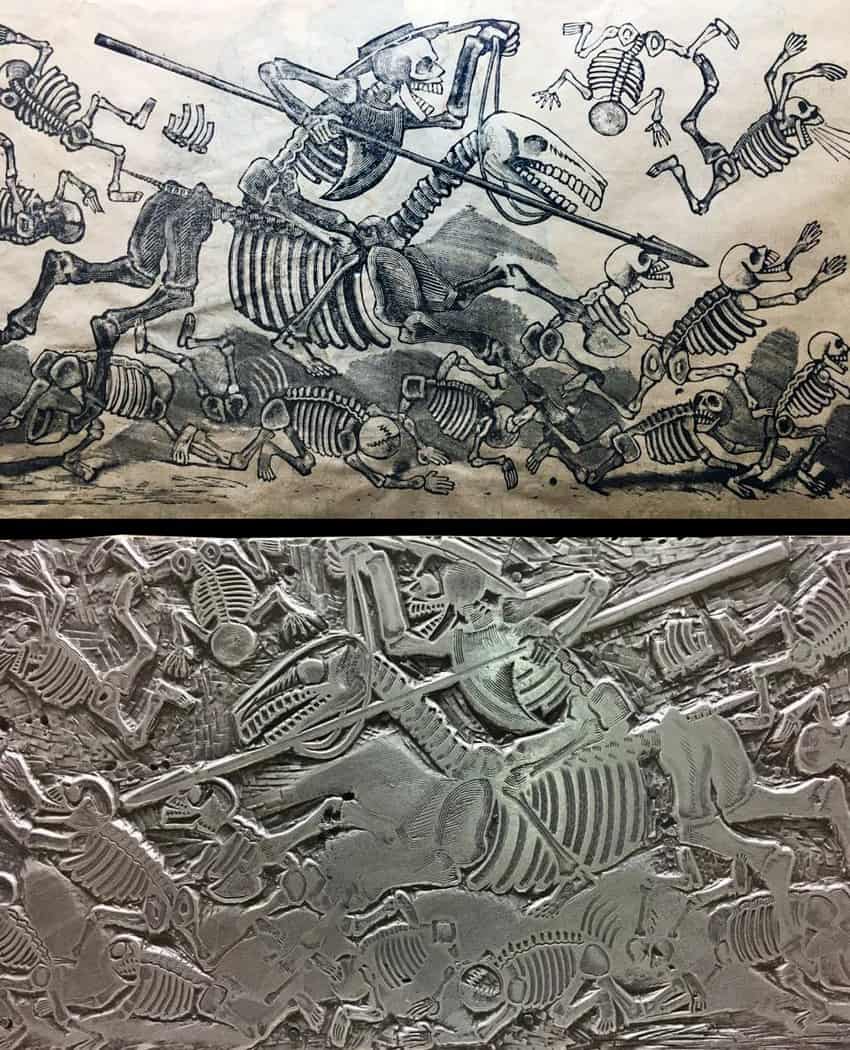

Posada then moved to Mexico City, where he collaborated with the newspaper La Patria Ilustrada and the Revista de México. For years, he had been doing his engravings on wood, but in 1895, he began experimenting with techniques of etching on blocks of zinc.

Mostly he did cartoons that were accompanied by verses or popular news items. The papers he worked for were penny publications, the precursors of today’s supermarket tabloids, and he illustrated countless tales of murder and mayhem as well as graphic reports of catastrophes and dire predictions of cataclysms.

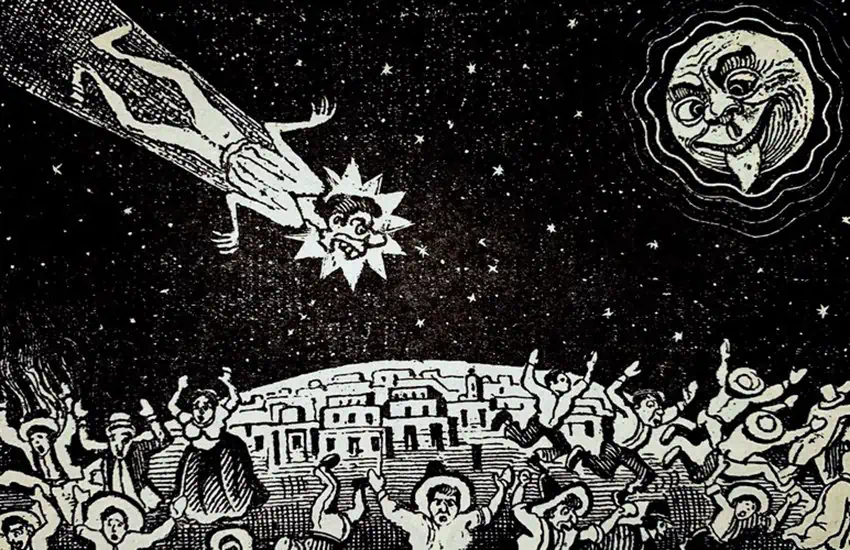

As for cataclysms, surely the most awful one predicted during Posada’s entire lifetime was Halley’s comet, which was expected to arrive in 1910. Well in advance of the comet’s arrival, famed French astronomer Camille Flammarion announced that the deadly gas cyanogen had been detected in Halley’s tail.

Because Earth was surely going to pass through that tail, Falmmarion predicted that the atmosphere would be impregnated with cyanogen and all life on Earth might possibly be snuffed out.

This prognostication produced panic all over the planet as people rushed to buy gas masks and phony “anti-comet pills” or “anti-comet umbrellas.” In Mexico, many churches were filled as the dread day approached and, in true Mexican style, fiestas were held “para despedirse de la Tierra,” to bid goodbye to Earth.

On May 19, Earth did actually pass through the tail of the comet, which put on a spectacular show, exciting stargazers and killing no one.

Posada’s cartoon pooh-poohed the calamitous predictions of doom.

José Guadalupe Posada’s first well-known representation of people portrayed as skeletons was his etching of a bony Don Quixote, published in 1905. From then on, the calavera became his trademark.

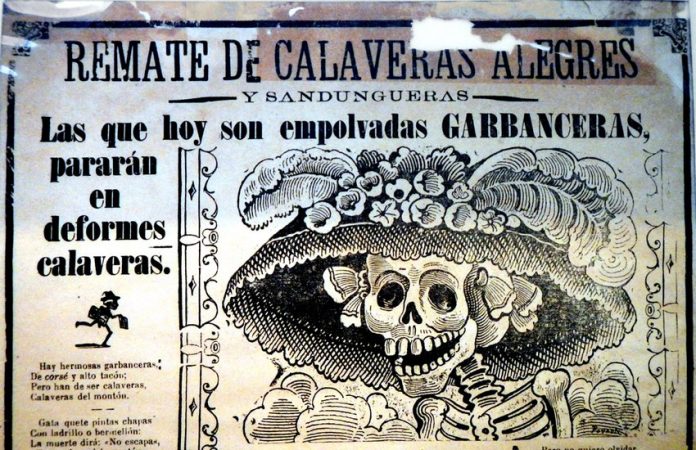

Calavera literally means “skull,” but in most cases, his calaveras were complete skeletons. In 1912, near the end of his career, Posada drew his most famous calavera, La Catrina.

Guides at the Posada Museum take pains to point out that, originally, Catrina was in no way related to the Day of the Dead, nor a mystical symbol of the inevitability of death, so predominant in pre-Hispanic Mexico.

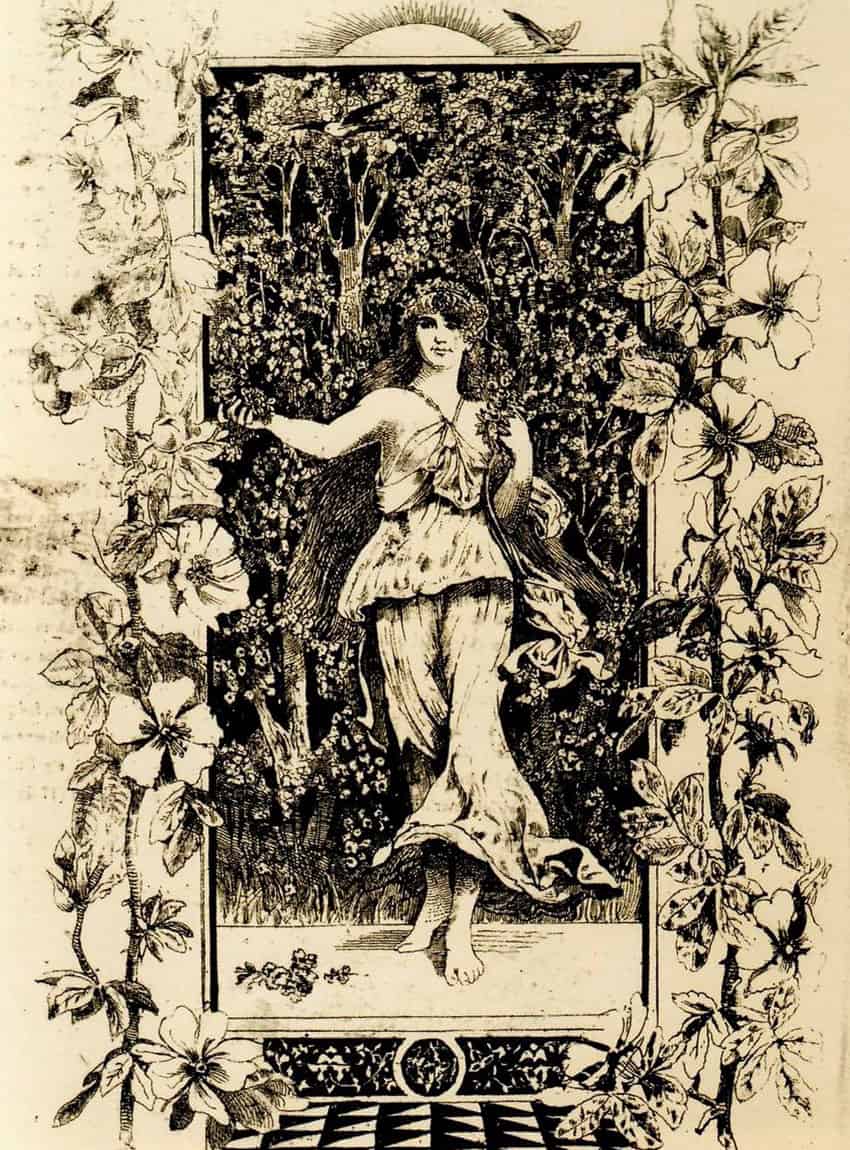

In reality, Posada’s Catrina poked fun at Mexico City’s high society during the Porfiriato — the period of Mexican history between 1876 and 1880 and 1884–1911 when Porfirio Díaz was president — when French fashions were all the rage.

Even servants and garbanceras (ladies selling chickpeas in the street) wanted to look catrín (fancy) and, one way or another, would borrow something French-looking to wear in public as well as whiten their dark skin with powder — in imitation of Porfirio Díaz himself, who went to lengths to hide his mestizo origins.

During all of his life, Posada worked for someone else, illustrating verses or stories written by other people.

“Posada does not want to reform or change society; he wants to depict it,” said Octavio Paz.

José Guadalupe Posada did such a good job at portraying things as they really are that the celebrated artist and husband of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, included him among the 150 most emblematic Mexicans in his 1948 mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda (Dreams of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park), which depicts 400 years of Mexican history.

In this 15-meter-long mural, Rivera painted a self-portrait of himself as a child, holding hands with Posada and La Catrina. He shows her wearing sophisticated clothing and an extravagant hat with feathers, thus creating the look that she is known for today.

The mural can be seen in the Diego Rivera Mural Museum in Mexico City.

Sad to say, José Guadalupe Posada died penniless in 1913 and, like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was buried in a dirt-cheap grave. Ironically, seven years later, the grave was dug up and Posada’s remains were thrown into the cemetery’s “calaveras del montón,” the very “heap of bones” which had appeared so often in his drawings.

Without a doubt, Diego Rivera would have agreed that the Posada Museum — with its collection of 3,000 pieces — is well worth a visit. It’s open Tuesday to Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. The entrance fee is 10 pesos general admission, and only five pesos for students and golden-agers.

You can reach them at (449) 915 4556 or via email or their Facebook page. The museum is free on Wednesdays and, yes, they have a Facebook page].

You can get there from Guadalajara in about three hours via very good toll roads, and it’s only a five-hour drive from Mexico City.

“Death is democratic, because in the end, everybody, whether light-skinned, dark-skinned, rich or poor, ends up as a calavera.”

— José Guadalupe Posada

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.