“If our main objective was to only serve the Jewish community of Mexico City we would have chosen a different location for the center.”

The words are those of Enrique Chmelnik, director of the new Centro de Documentación e Investigación Judío de México (the Center for Jewish Documentation and Research in Mexico) in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma.

“There have always been these windows through which the Jewish community looked out at Mexico and Mexico looked back in at the community. We see this center as a grand doorway between the two.”

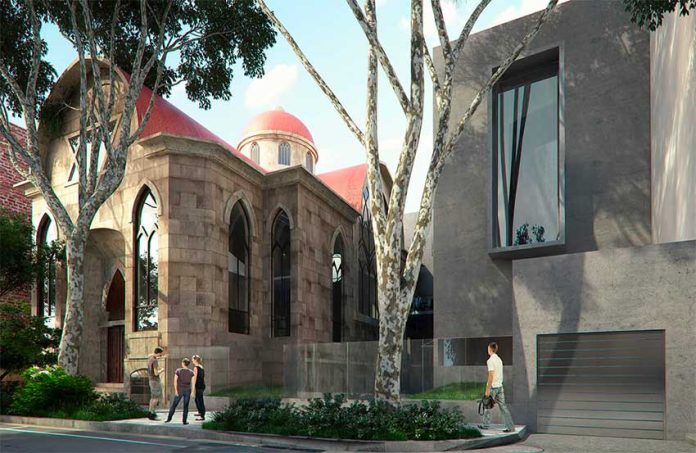

We are seated in the center’s sleek and modern glass-walled conference room that looks down over one of Mexico City’s oldest synagogues. Sunshine shimmers through Star of David windows, casting red, blue and yellow shadows on the synagogue’s central atrium, now a library housing hundreds of donated books.

In 1938 this synagogue was the home of the Maguen David Jewish community, the place where their children married, where prayers were recited, and home of the city’s oldest mikveh, or ritual bathtub. As tiny specks of dust glitter among the silent chandeliers, the echoes of the community still vibrate in the walls.

Jewish history in Mexico City is complicated, explains Chmelnik. Despite the fact that most Jews live in similar neighborhoods and are surprisingly unified as a community within Mexican society, the community itself is fractured into several groups.

There have been Jews in Mexico since the country’s colonialization, he says, but an established community that identified strongly with its Jewish heritage really didn’t appear until beginning of the 20th century.

The majority of Jews that immigrated to Mexico came from Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, some seeking religious freedom, others refuge from persecution; some looking for economic opportunities and others, including artists, poets and scholars, encouraged by the Mexican government for their European influence.

In 1912 the inaugural Jewish community was founded here, Sociedad de Beneficencia Alianza Monte Sinai, but 10 years later the first schism erupted when Ashkenazi Jews separated from Monte Sinai to form their own community. Two years later, Jewish immigrants from Mediterranean countries formed the Sephardi community, and in 1938 Syrian Jews from Allepo decided to separate from Syrian Jews from Damascus and form the community Maguen David.

According to Chmelnik, these divisions were incited by arguments over religious practices, hierarchies within the Monte Sinai community and the major cultural differences among the groups. They came from different countries, with different experiences and many different languages. While their religious traditions were similar, there were certain details that the groups felt they couldn’t overlook.

Today, few Mexico City Jews speak Arabic, or Polish or Yiddish and many aren’t religious enough for different prayers to make much of a difference. That’s why the center, which is trying to create a cross-community Jewish archive, thinks it has a good chance at success.

“Every day we are getting closer to unifying,” says Chmelnik, “and each year there are more cross-community organizations like this one. And I’ll tell you one thing that will definitely put an end the separation at some point in the near future: 70% to 80% of all Jewish marriages in Mexico City are among members of different communities.”

The roots of the archive go back to the 1990s when the Mexico City Ashkenazi Community was celebrating its 70th anniversary as a community. In the process of creating a commemorative book for the event, historians filtered through hundreds of documents and items in the basement of Acapulco #70, an important center for Ashkenazi Jews in Mexico City. What was there was in poor condition and an idea was hatched to preserve the historic documents in an official archive.

In time, the growing collection was added to UNESCO’s World Memory Program and talks began among the various communities to expand the archive’s breadth to not only include documents from the Ashkenazi community, but each of the others as well.

“The idea was to have the entire history of Jews in Mexico under one roof,” says Chmelnik.

By 2015 a communal archive was already in the works, with representatives of each community signing on to the project. Then the September 2017 earthquake hit and Acapulco #70 was damaged beyond repair, but volunteers and members of the community were able to rescue the archive.

Its new building at Cordoba #238 was already in the works and so plans were sped up to move the offices there as quickly as possible.

The new center opened in January of this year, its priority to collect each community’s archives, according to the inter-community agreement, and build the most important Jewish studies center in the country.

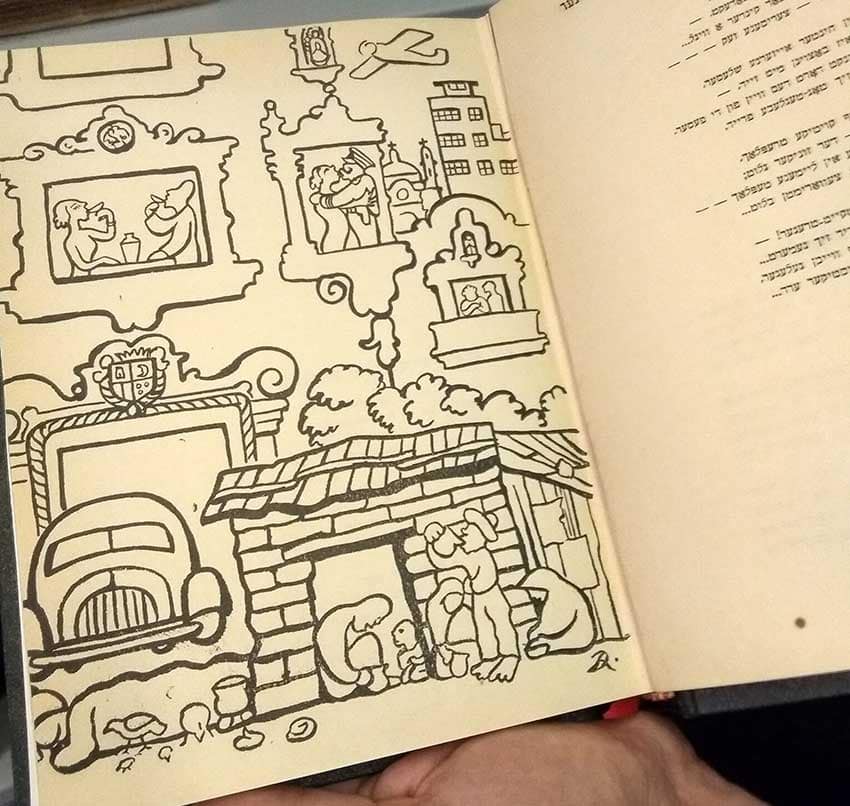

“This is a book by Yiddish poet Issac Berliner,” says Chmelnik opening the pages from right to left and landing on an illustration that looks vaguely familiar. “He was a good friend of Diego Rivera and so Rivera illustrated his book for him.”

We are standing among the metal bookshelves within the synagogue’s basement. There’s a chill in the air, which is not just the humidity-controlling air conditioning unit.

Tomes from a Nazi library in Berlin are among some of the archive’s oldest items. The Third Reich’s confiscated books were supposed to “prove” the dangers of Judaism, and therefore justify its eradication.

By the time the allied forces found this stash, most of the books’ owners had been killed. So they sent books, a bundle at a time, to Jewish communities across the globe, including 1,000 to the Ashkenazi community of Mexico City.

Posters protesting World War II are carefully preserved in thick plastic, signs defaming Jews are there along with them. Shelves stacked with photos and marriage certificates tell the history of the communities through the eyes of their members, the unofficial story as Chmelnik likes to say, the one you don’t find in newspapers and meeting minutes.

There are menorahs and mezuzahs of every shape and size, handwritten letters, journal entries – all once belonging to someone who is no longer here to tell their own story.

Authors researching books, community members researching family lineages and students searching for primary sources all find their way to the archive. While a long string of cultural activities fills the center’s docket, research here and in their library is by far their most important service offered to the public.

And while for the time being Mexico City’s Jewish community may remain segmented, this archive will serve as a safe home for the remnants of each of their separate histories, which is the legacy of them all.

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer based in Mexico City.