The first curious thing about Obsidian Island is that it is surrounded by great stretches of farmland and is not an island at all. The second curious thing about it is that it has no natural deposits of obsidian whatsoever.

After that, the list of the mysteries of Atitlán — as it was called in ancient times — only grows longer.

Today this ex-island is called El Cerro de las Cuevas (The Hill of the Caves). It’s located next to the little town of San Juanito Escobedo in the state of Jalisco, 60 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara.

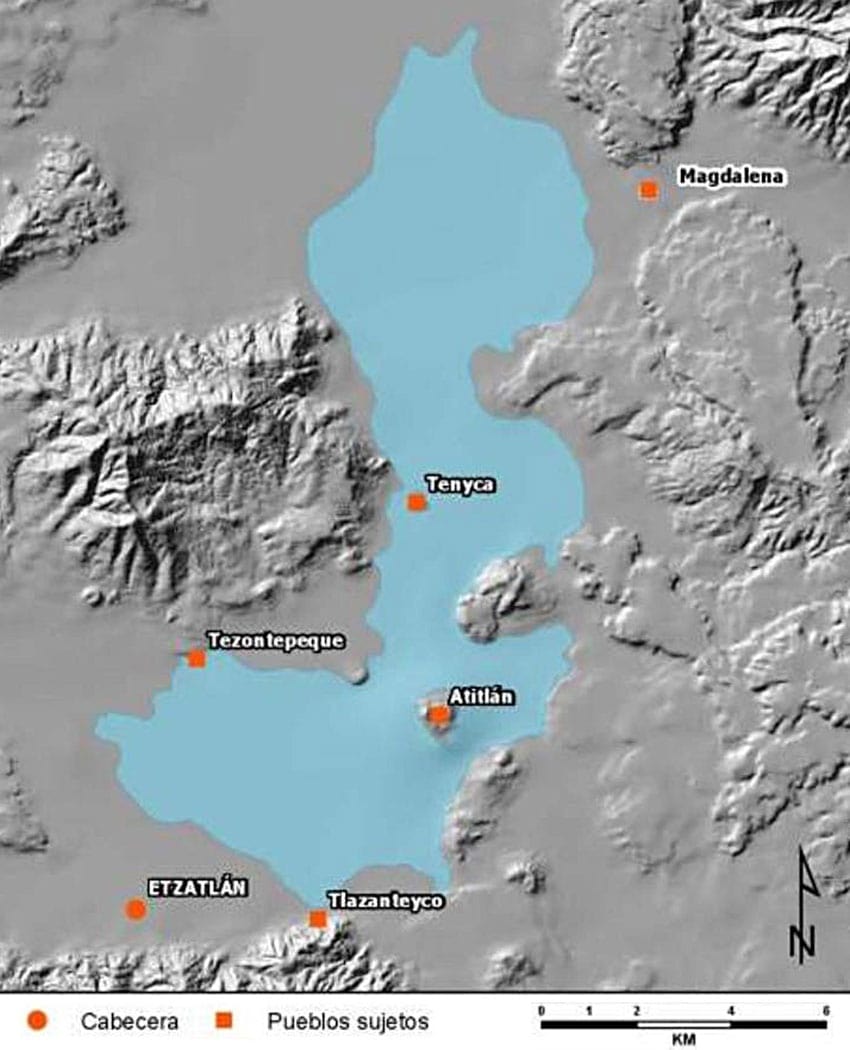

I was first introduced to the place by archaeologist and obsidian specialist Rodrigo Esparza. As we approached San Juanito, Esparza explained that the farmland we were driving through was once covered by the Laguna de Magdalena, a lake more than 70 square kilometers in size that had been a major feature of the Jalisco landscape until, in 1930, the Mexican government decided to dry it up, said Esparza, “in order to create more cane fields.”

A narrow dirt road skirts the west side of the Cerro de las Cuevas, and here we passed several dark openings: artificial caves, hand-carved in the soft jal or volcanic tuff.

We stopped in front of Esparza’s favorite cave. “From here,” said the archaeologist, “it is possible that people carried out ceremonies while contemplating the lake, whose shore was about 40 meters from the cave.”

After exploring some of the other cuevas (caves), we headed up the hillside on foot, our pants and shoes collecting great numbers of huizapoles (burrs) along the way. We soon came to a hole about two meters deep. This had been dug by tomb robbers, and its walls gave us a good look at what had been going on at this site for hundreds of years.

“As you can see, the ground beneath our feet is a two-meter-thick layer of dirt filled with discarded fragments of obsidian tools,” Esparza explained. “This is by far the largest obsidian workshop I have ever seen.”

Geologist Chris Lloyd then jumped down into the pit and began pulling pieces of obsidian out of one wall. There were broken arrowheads, flat blades with sharp edges and bits of other artifacts.

“All of these are the throwaways,” said Esparza, “and the pieces down at the very bottom of the wall may be 2,000 or 3,000 years old.”

We were amazed to learn that none of these obsidian artifacts was native to the island itself.

“All of this obsidian originally came from a nearby deposit known as la Joya, located six kilometers northeast of here,” Esparza said. “We proved this through neutron activation analysis. Exactly why they brought the obsidian here to this island to work on it is a mystery that needs to be investigated.”

Next, we headed further up El Cerro de las Cuevas, naturally acquiring plenty of new huizapoles. At last, we came to a flat spot, where we gazed upon blocks of stone covered with weeds, all that’s left of the first Christian chapel in this part of Mexico, built by the Franciscans sometime in the 1530s.

This building measured about 8 by 12 meters and was probably quite magnificent in order to impress the locals. Apparently, however, the locals were not terribly impressed because it’s documented that one day they rose up and killed all the friars (six of whom are now considered saints by the Catholic Church).

After this history lesson, we hiked to the very top of the cerro, acquiring yet more burrs, as well as numerous scratches from thorns, plus a few punctures from agave spikes. At last, we stood upon a lookout point from which we could clearly see kilometers of cane fields all around us, making it easy to imagine the impressive extent of La Laguna de Magdalena back when the Spaniards first arrived here.

All the researchers who have visited Atitlan seem to agree that something important had been going on there. In 1896, British Explorer Adela Breton included Obsidian Island among the places she visited during her hunt for archaeological ruins in Jalisco.

In modern times, newspapers have claimed that it is home to a pyramid, a ball court, numerous tombs and an ancient harbor, but no one, it seems, ever documented such findings, nor has any serious research been carried out to discover just what it was that puts Atitlán in the running for the biggest and longest-lasting obsidian workshop in Mexico, and perhaps the world.

All this changed in 2010 when Jalisco archaeologists asked the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) to launch a proper research project to look into the mysteries of Obsidian Island.

“We are presently in the second stage of a program for studying this former island,” says researcher and project director Ericka Sofía Blanco.

Blanco served as director of the Phil Weigand Interpretive Museum at Teuchitlán, Jalisco, for five years and now directs the project to investigate the long history of Atitlán.

“The first stage involved a detailed study of previous research and historical documents related to both the island and to the Laguna de Magdalena. Next, we will be carrying out excavations and doing lab analyses.”

Before its draining in 1930, Blanco told me, the Magdalena Lagoon played an important role in the economy of the populations located along its shore. Just one example, she said, was the petate (a sleeping mat made of reeds) industry, which was vital for the people of San Juanito Escobedo before the lake disappeared.

“If the lake was important to the modern-day economy,” she added, “it was even more important to the pre-Hispanic economy.”

As for the extensive working of obsidian on the island, Blanco discussed an important obsidian workshop discovered in the 1980s by archaeologist Phil Weigand.

“As we begin to dig in various parts of Atitlán, we see that this wasn’t a normal obsidian workshop, but it seems the artisans were manufacturing tools for use right here on the island, for some industry or activity related to the Lake of Magdalena, to the economy of the island.”

Blanco noted that all the knives and scrapers they have dug up have scratches, both visible and microscopic, indicating that they were used to cut and scrape something.

“We see these wear marks as well as vestiges of so-far unidentified vegetable material, telling us that there was some sort of important industry operating on this island. It looks like they were supplying something important to all the communities surrounding the lake. Whatever it was, it had to be important because this was a macro-operation, spread out over a space of three hectares. It was impressive!

“We should always bear in mind that water was the most convenient medium for travel in pre-Hispanic times. Atitlán Island was strategically located to serve a huge area, all points of which could be reached easily and quickly by boat. We still don’t know exactly what they were up to on that island, but we are constantly finding more clues, and we are making progress.”

The UNAM team has found indications of habitation of Obsidian Island from at least the year A.D. 400 right up to the arrival of the Spaniards — and there are strata below this level that they haven’t even looked at.

“We have also uncovered the remains of a rectangular platform,” says Blanco, “a public meeting place in the style of the El Grillo Phase (A.D. 500–900).”

UNAM’s multidisciplinary team working at Atitlán collaborates with many other institutions and this year received financial support from the municipality of San Juanito Escobedo.

“We also got assistance from Diputado Eduardo Ron and many local shopkeepers who help us out with supplies,” says Blanco.

I asked her how she became interested in archaeology, and she mentioned Raiders of the Lost Ark.

“As a young girl,” she replied, “I was enchanted by the romantic Indiana Jones concept of the intrepid archaeologist, but then my family asked, ‘How will you ever make a living with that?’ So I ended up studying business at the Autonomous University of Guadalajara (UAG). Well, at one point, we had to do a dissertation related to some field totally unrelated to business, and I decided to investigate and describe the Wixárikas, the indigenous people who live in the Sierra Occidental.”

She enjoyed the process, and her advisors liked her work, she said.

“… so I went home and said, “Mamá, I’m really sorry, but I can’t dedicate my life to something I don’t love; I want to be an anthropologist.’ Fortunately, it turned out the UAG was offering this career, and now here I am!”

We look forward to receiving more news from her as the UNAM team unravels the story of mysterious Obsidian Island.

[soliloquy id="135585"]

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.