He was the only Latin American to execute a military raid on the United States.

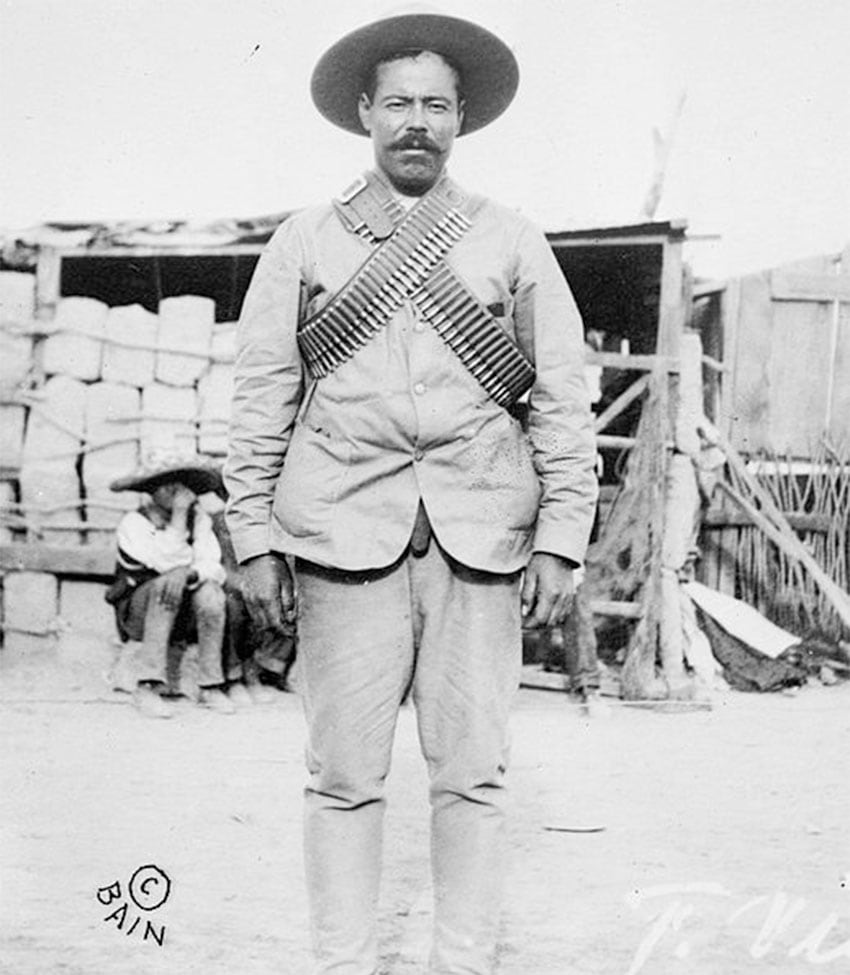

Best known as Pancho Villa, the Mexican Revolution general was born Doroteo Arango in 1878 in Durango. His life of violence and flight began early, after killing an hacienda owner who had assaulted his sister.

Villa joined the fledgling Mexican Revolution in 1910. Well-known in the mountain backcountry of Durango and Chihuahua, he recruited rebels and formed his own army, the División del Norte, which rose to national prominence, allied with other revolutionaries such as Emilio Zapata, Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón against the Victoriano Huerta regime in 1913.

But the alliance quickly split into two factions, with Villa and Zapata pitted against Carranza and Obregon. At one point, Villa and Zapata took Mexico City.

But in 1915, Carranza pushed the two out of the capital, beginning a long retreat northwest for Villa. This pushed him out of the national spotlight, but he remained a major force to contend with in the north.

Carranza painted Villa as a violent, crazy bandit in both Mexico and the U.S. — with some basis in reality when it came to highway robbery and cattle rustling. The depiction was one reason why U.S. president Woodrow Wilson decided to back Carranza and deny arms and other support to Villa.

This shift of allegiance by Wilson was the reason behind Villa’s actions against the United States. They were not the acts of a madman; Villa’s aim was to draw the U.S. into the civil war that had engulfed Mexico post-Revolution, and make the Mexican people think of Carranza as a U.S. puppet.

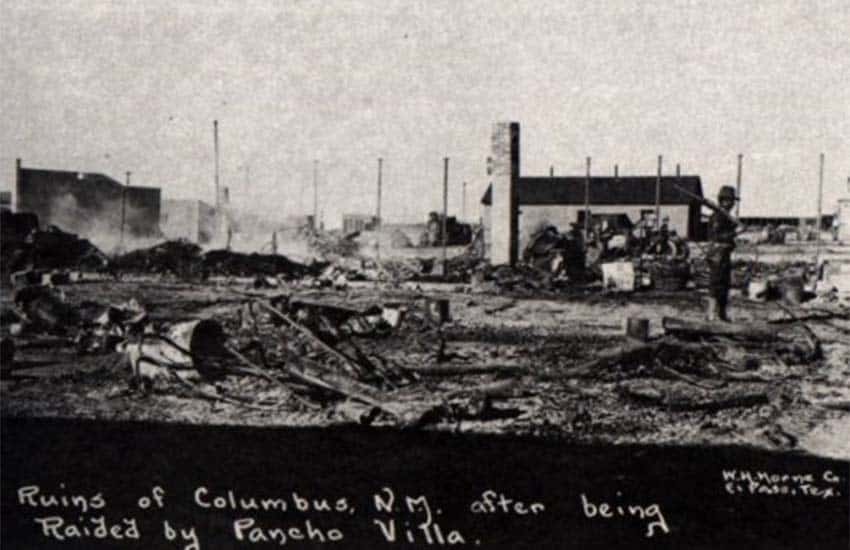

Villa’s plan began with an attack on a train in northern Mexico in January 1916, executing 16 U.S. businessmen onboard. It ended with small raids on the Texas towns of Glen Springs and Boquillas in May. But it was his attack on Columbus, New Mexico in that same year that would cement him in U.S. consciousness.

In this attack on March 9, more than 600 soldiers entered the border town, killing dozens of Americans and setting the town on fire. The actions had the desired effect: widespread anger in the U.S, even calls for another wholesale invasion of Mexico.

Wilson’s answer was the Punitive Expedition, two waves of forces under General Pershing that spent 11 months scouring northern Mexico to capture Villa.

But no one knew the backcountry of northwest Mexico like Villa did, plus the people of the region were solidly behind him and hostile to the foreigners. While Carranza had given reluctant permission for the Punitive Expedition, he refused to help them, although he definitely wanted Villa out of the picture.

The Punitive Expedition put both Carranza and Wilson in a bind, especially as it wore on with no results except for a few skirmishes. Eventually Pershing was recalled in January 1916, with Villa still at large.

Villa turned to guerrilla tactics, harassing the federal government for as long as his enemy Carranza remained in power. Neither he nor Zapata became president, like many other generals of the revolution did, but their constituencies could not be ignored. Many of the social reforms in Mexico’s constitution, drawn up in 1917, are due to their influence.

More than 100 years before the term was coined, information warfare played an important role in Villa’s rise and fall, as well as his legacy after the war.

Newspapers on both sides of the border alternatingly painted Villa as a violent madman or a Robin Hood figure. Newsreels had recently become available to the general public and were often faked for propaganda purposes, or simply for increased dramatic effect. Villa himself worked with camera crews from the U.S. on several occasions, even wearing uniforms provided to him. He may have also recreated images of fighting for the cameras.

In Mexico, Villa’s military fall gave him a lower status in the country’s history, but he remains extremely popular in the north, especially in Chihuahua and Durango. His popularity there is not only because he is their native son but also because norteño culture is more affected by Mexico-U.S. relations. He is a hero in part because he challenged the mighty United States and kept his life.

Villa is one of few Mexican historical figures known to many in the U.S. Despite their country’s involvement in WWI, citizens of the time were fascinated by the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. This fascination sparked a demand for cinematic and other depictions that remains to this day. Villa himself appeared in various U.S. films from 1912 to 1916 and has been portrayed by many Mexican and American actors since.

Despite his wild and brash reputation, Villa ended his animosity against Mexico City with a negotiated settlement that had him “retire” from politics on a large hacienda in Canutillo, Durango. That retirement lasted only three years, however, before he was assassinated in Parral, Chihuahua — not by anyone from the U.S. government but rather domestic political enemies.

It is worthwhile to note that Columbus, New Mexico, has a Cabalgata Binacional (Binational Horse Riding Event) each year on the anniversary of the attack on its city. Perhaps one reason why Villa’s story resonates on the U.S. side of the border is begrudging respect for a man willing to grab the tiger by the tail.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.