One of the lesser-known benefits of cave exploring in Mexico is the occasional natural wonder you stumble upon while beating the bush in search of a cavern.

On many an occasion, that elusive cueva (cave) turns out to be a mere socavón, just another hole in the ground that no self-respecting bat would ever deign to live in. Ah, but that natural wonder discovered along the way could be anything from a dazzling waterfall to a stupendous mirador or lookout point: a veritable jewel that only the folks in the local ranchos know anything about.

One of the best examples is what I call the Hot Pool of Paradise.

Many years ago, I was examining the topographic map for Ceboruco Volcano in Nayarit and spotted a place called Las Cuevas not far from the little town of Verde Valle.

On one fine day off, we went to Verde Valle, where a local beekeeper confirmed that we would indeed find caves at Las Cuevas and told us how to get there:

“Just follow the railroad tracks and turn right after four kilometers,” he said.

This we did, and nailed to a tree at that exact spot we found a sign for Balneario Los Cocos, a name indicating that we had encountered a natural spa. Caray, we thought: a noisy water park here in the middle of nowhere? ¡No es posible!

But for the sake of those marvelous caves we were after, we continued right on. The road turned out to be so rough that our worries about finding taco stands at the end of it soon vanished.

For 2.5 kilometers, we bounced along that poor excuse for a road until, on our left, we spotted the shelter cave — about 15 meters long and 10 meters deep, offering fine protection from the elements.

Its well-blackened, slanted ceiling suggested that people had been using it for this purpose for many, many years. This place, to our surprise, was “furnished” with tables, chairs and a stove, all made of flat rocks; it even included an old grave.

A horseman then came by and told us that the cave was being used every year as a temporary home for workers during the harvest season.

“This cueva,” he told us, “used to be very deep and long, but the passage leading to the rest of it has been sealed off because vampire bats would come out of it every night and scare people. It doesn’t look like it, but this cave goes all the way through the hill. If you go around to the back of it, you will find the other entrance.”

Just past the cave, we came to a nice-looking lagoon, which was actually a dam. The water was lukewarm, and we could see fish jumping in it. Here we parked and began walking around to find a good camping spot.

“How about under that fig tree?” I suggested.

To our great amazement, the moment we stepped beneath the tree’s spreading branches, it began to rain; the moment we stepped away from it, the rain stopped. Among us was naturalist Jesus “Chuy” Moreno, to whom we immediately turned for an explanation. Chuy climbed up onto a low branch and came back down with a bug in his hand. It somewhat resembled a grasshopper, but it was gray and fuzzy.

“This,” he announced,” is what’s causing the ‘rain.’ But it isn’t rain at all: these insects are peeing on us!”

There was a brook (the source of the lagoon) flowing next to the fig tree, and we followed it upstream to its origin, a hot spring bubbling up in the middle of a shallow, natural pool with a sandy bottom. Somebody had conveniently channeled its outflow into two artificial swimming pools, giving us three different bathing temperatures to choose from. It seemed that we had found Balneario el Coco but without the crowd and the noise!

This was obviously the ideal place for us to camp. We immediately got busy cooking supper.

“For dessert,” I announced, “We’re going to have cajeta [caramel] which I am going to produce by simply heating this ordinary can of sweetened condensed milk.”

I was about to open the can when Chuy stopped me.

“No, don’t open it,” he insisted. “My mother makes this all the time, and you shouldn’t open the can.”

“Okay,” I said. “Mom knows best.” And so I placed the can on top of some hot coals in the campfire.

Something then distracted me, and I completely forgot about my cajeta delight until we all heard a tremendous bang.

A great white cloud shot straight up into the air above the campfire.

“The cajeta!” I cried as white rain fell back down, coating every one of us with sugary goo. Only later did we learn that the unopened can should be placed inside a pot of boiling water, not directly over a flame.

Fortunately, the hot spring was right at hand for removing that sticky residue. When night fell, steamy vapors began to rise from the shallow pool, which was surrounded by exotic plants that look like wild pineapples festooned with yellow ping-pong balls. The water was crystalline, amazingly transparent, and its temperature was 38 C — perfect for a soothing hot bath on a cold winter’s night. In that delicious hot pool, we lay on our backs on its sandy bottom, staring up at the stars, hunting for meteorites, while we were serenaded by a big brown owl hooting from a branch far above us.

“This,” we decided, “may be as close to paradise as we’ll ever get.” And the name stuck.

We spent the next day hunting for a cave entrance on the other side of the hill.

“Look for a clearing,” our informant had told us, “with a cabra tree in the middle of it.”

Now, we had never heard of a cabra tree, but we were told that its fruit comes in pairs “that look like large hog’s balls,” just the sort of thing we were sure we couldn’t miss.

As we beat about the bush (with nary a clearing to be seen anywhere), we spotted iguanas, squirrels and lots of birds, such as motmots, orioles, hawks and sleek wild turkeys. We also came upon some impressively spiked pochote (silk cotton) trees, one of which was home to a mysterious great black ball on its trunk, which turned out to be hundreds of daddy longlegs all huddled together in a quivering black mass. We even came upon a few of those hog’s-ball trees.

Yes, in the course of the morning we spotted everything but that cave, and we eventually came to the conclusion that the real treasure of Las Cuevas is its enchanting Pool of Paradise.

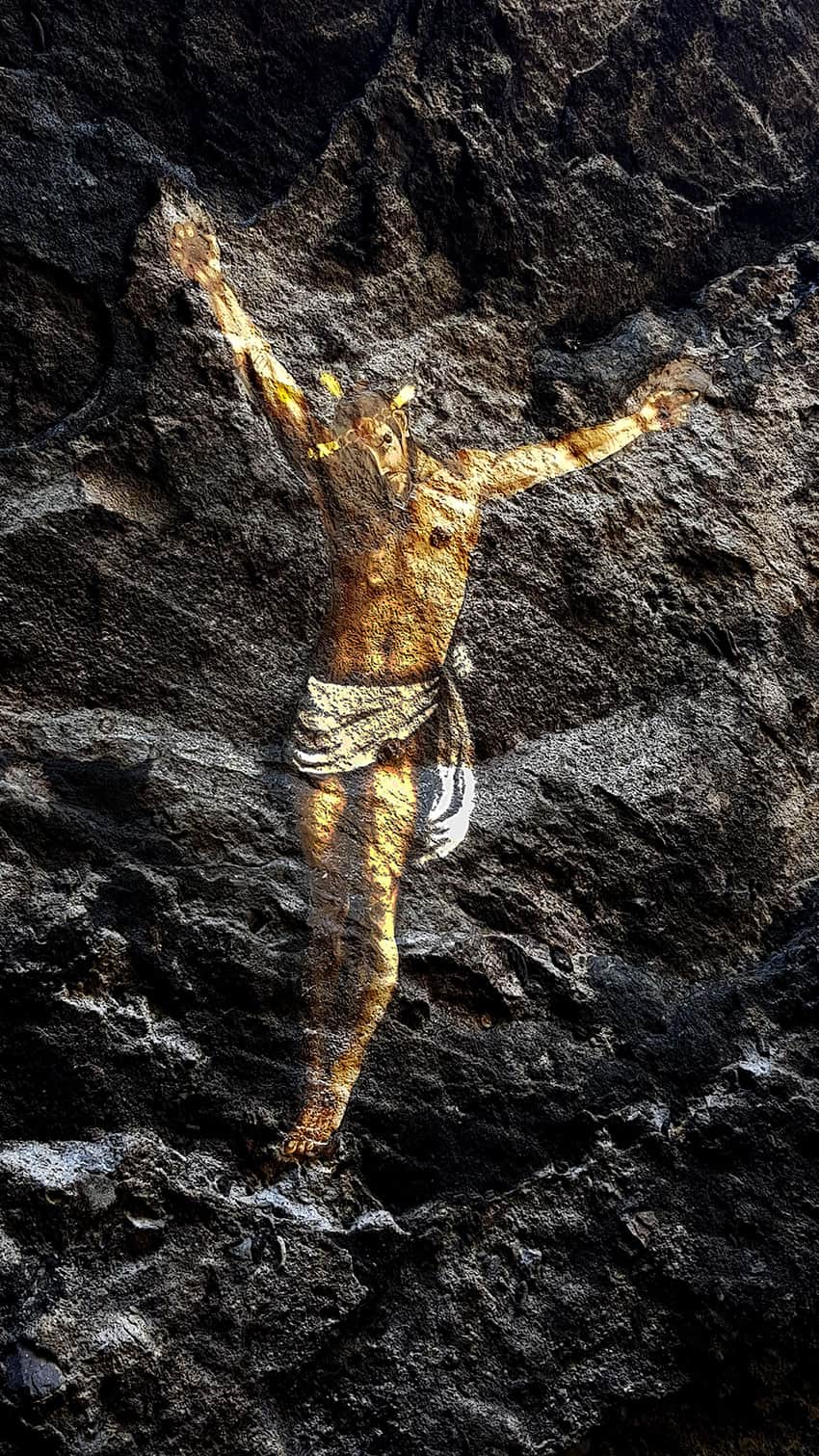

I returned there a few weeks ago, and I’m happy to report that the only development has been the transformation of the shelter cave into a kind of church. The hot spring, however, is just as rustic — and delicious — as ever. Should you go there on a weekday you will have “paradise” all to yourself, but on Sunday afternoons and evenings a lot of locals come here to picnic and bathe.

If you have a high-clearance vehicle and a weekday at your disposal, ask Google Maps to take you to “48HJ+7F Corral Falso, Nayarit.” This will get you to within two kilometers of the lagoon, cave and hot pool.

To cover the rest of the distance, switch to satellite view, and you can easily see how to get farther north to the lagoon, which is also very visible. The shelter cave is on the left side of the road, 200 meters south of the lagoon; the hot spring is 300 meters north of the lagoon. And now, Paradise is yours!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.