Long ago we heard rumors that the petroglyphs of Altavista — located 50 kilometers north of Puerto Vallarta as the macaw flies — were a sight we had to see.

Finally, one day in March, we decided to go visit the place, figuring that this time of year the humidity and the gnat count would be low while the temperature would be pleasant by day and cool at night: perfect ingredients for camping on the beach at the nearby pueblito of Chacala.

We left Guadalajara at 10:00 a.m. and by 1:30 p.m. we were pitching our tents in a most unusual setting: the ruins of the ancient munitions armory of the port of Chacala, one of the deepest natural harbors of the Pacific Coast and for many years a favorite hangout for pirates.

At a little table dwarfed by huge stone columns long ago overrun by strangler figs, we shared a bottle of wine with the owner of this ruin, now converted into a hotel and mini-campsite. “My name is Om,” she told us, “and I love Chacala so much, I spent nine years here living in a tree.”

The next day, we couldn’t resist hiking down the beach to see Om’s tree house (the rope ladder is still dangling from the branches) and to visit a volcanic crater which overlooks the gorgeous little beach of Las Cuevas, and — well, there was so much to see, our visit to the rock art of Altavista got pushed off to the last day. But we finally managed to get there and discovered that this out-of-the-way spot is well worth the effort required to reach it.

Because we could see no signs indicating where to go, it took us two attempts to find the place. The road to the town of Altavista is just off Highway 200 to Puerto Vallarta. Before reaching the town, we turned left onto a dirt road which was in quite good condition, but only for 875 meters. At this point, deep and ugly ruts could be seen just ahead, so here we parked and started walking.

On our right was a huge grove of flowering mango trees and on our left we came upon a farmer spraying his rather sad-looking trees with sulfur. We figured this must be an insecticide, but he told us the treatment was meant to “estresar los árboles” (to make the trees feel stressed out) so they would flower. It looks like there’s no escape from the pressures of modern life, even for trees!

Soon the narrow dirt road turned right (and shady, and flat). Our 1.7-kilometer walk took 45 minutes and ended at a gate where we found big INAH (National Institute for Anthropology and History) signs listing numerous things we were not allowed to do (including applying chalk to the grooves of the rock art). We also found a guard who charged us 20 pesos each to enter the fenced-in zone.

We were now on a trail paralleling Las Piletas Creek, which — because it was the dry season — contained only occasional puddles of water. Every few steps we came upon large, hand-lettered signs in English and Spanish telling us all about the native people who once lived here and who created the petroglyphs. Most of this information originated with west-Mexico archaeologist Joseph Mountjoy and was truly fascinating.

These Indians turned out to be members of a tribe I had never heard of: the Tecoxquin, whose favorite sport, according to the signs, was cutting off the heads of their captives for ritual sacrifice. It is said that the Tecoxquin inhabited the area as far back as 2300 BC and were wiped out during the Conquest by a combination of European disease and the Tecoxquins’ refusal to become slaves.

Soon the trail was winding between and over large boulders: not the sort of place you could push a baby buggy or hobble along with a bad leg. Scattered among the rocks, however, were a variety of quite curious petroglyphs: several boxy, cartoon-like shapes sporting a dozen or so “legs,” a number of elaborately carved crosses, and a humanoid figure who seemed to have a graceful tree growing out of his head. One of the designs cleverly used deep pockmarks as shading and to me (and no one else!) resembled a rabbit-like creature with whiskers.

It seems around 2,000 petroglyphs have been registered along el Arroyo de Las Piletas, of which 56 can be seen in the area reserved for visitors. Archaeologists think these images represent a kind of prayer to the Tecoxquin gods, begging them for rain, good crops, good weather, etc.

Of course there are spirals at Altavista, as there are at just about every petroglyph site I’ve ever seen. As for their meaning, a sign at Altavista mentions that spirals “have been interpreted as the sun, rainstorms, the wind, coiled snakes or as a symbol of the natural rainy and dry cycle.” Other sources say they may represent water sources, the solstice, migrations, whirlwinds, snails, growth, energy and lots of other things, all of which seem to leave the door to interpretation wide open.

Historical records dating back to 1612 note the Spaniards’ surprise at finding numerous crosses among these petroglyphs. Some of these resemble a cross potent or Maltese Cross and helped give rise to legends about the apostle Saint Matthew having set foot in these parts. Easier to believe is the most common interpretation, that the crosses represent the five directions: north, south, east, west and “right here where you are now.”

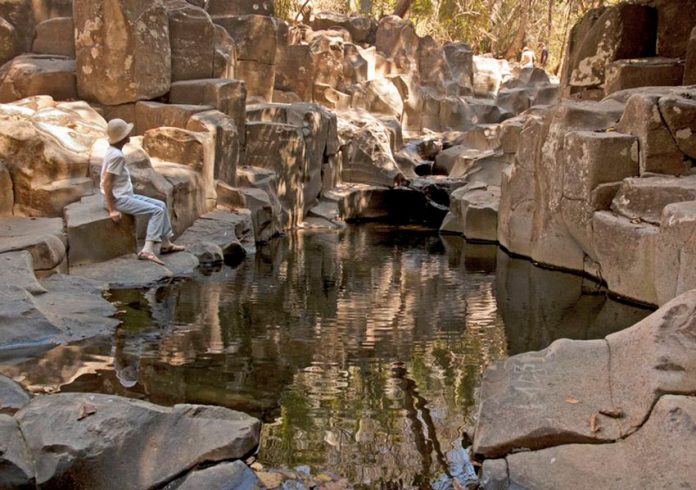

Although the petroglyphs are most interesting, to me the most impressive attraction of this site is the so-called Pila del Rey, the Bathtub of the King: a pool of icy cold water, fed by a spring even in the dry season and surrounded by huge rectangular rocks, probably columnar basalt. This place looks like something straight out of a fantasy novel and will no doubt one day appear in some Hollywood extravaganza.

I asked Dr. Mountjoy who the “King” might have been, but he suggested the name Pila del Rey had more to do with tourist appeal than historical fact. Nevertheless, this must have been an awe-inspiring place 2,000 years ago and it remains so today.

The petroglyphs are located about 10 kilometers south of Las Varas, Nayarit. The park entrance is at N21.09201 W105.16624. Because it’s a tricky place to find, you may want to ask a touring company like Mexitreks to get you there.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id="102535"]