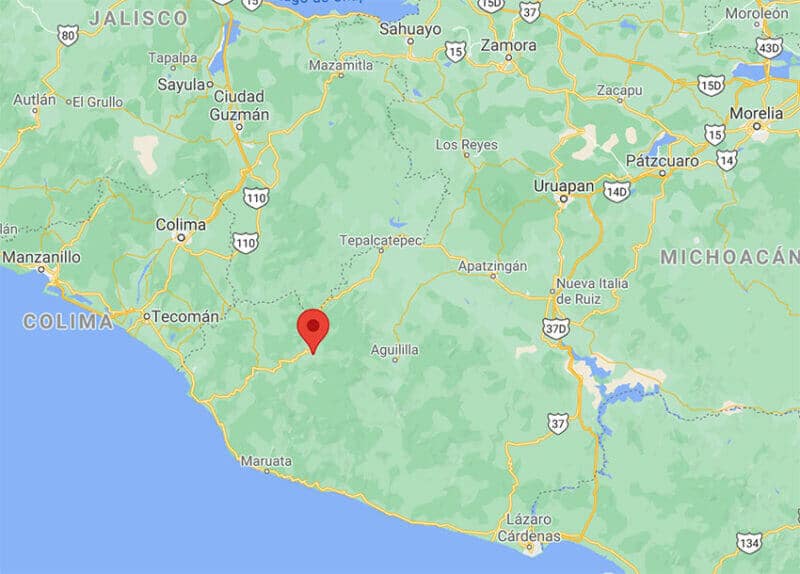

Hundreds of families — and counting — in the Michoacán community of Coalcomán have been displaced by narco violence in the past week as cartels continue fighting for territory in the Tierra Caliente region.

Local and religious authorities say the number of refugees has grown exponentially in recent days, and social media posts have shown entire families leaving their homes on foot with nothing but a few suitcases.

Authorities estimate that around 600 families, or 3,000 people, have been displaced from rural areas of the municipality in recent days. About 120 are currently lodged in the municipal capital in a small auditorium that has been converted to a shelter.

Local officials fear that the density of people will lead to violence or Covid outbreaks, but see no other option for housing the displaced. Other refugees have found shelter with family members and still others are on the street. The local government asked state authorities to allow them to use certain buildings as shelters, but were denied.

People are fleeing not just because of the armed confrontations between cartels, but also due to the scarcity that the violence has caused. Electricity, water, phone and internet services have all been compromised and food is running short, since armed groups have blocked the roads into and out of the area.

Some residents have been directly threatened and told to leave.

“The armed men threw family members out of their homes and ranches and now have also taken their livestock and their land, so they don’t have anything left,” said one Coalcomán resident who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Residents of nearby municipalities like Tepalcatepec, Apatzingán and Chinicuila have gathered donations to provide food and clothing to the displaced people, even as they themselves are caught in the crossfire of cartel violence.

Local Catholic priest Jorge Luis Martínez Chávez said Coalcomán was formerly a calm, prosperous area. The population of roughly 12,000 people worked in agriculture, ranching, forestry and business. But now, he said, “they have stolen our peace.”

“We have been dragged into the war between cartels; we live in a situation similar to that of Aguililla. The people live with the uncertainty of violence … burned cars, blocked highways, assassinations everywhere, forced exile, the destruction of the road … the destruction of telephone lines, little internet access and surrounded by armed people who defend their own interests,” Martínez said.

Residents have gone to the local military base for help, but were told that the armed forces could do nothing without orders from above, Martínez said, describing the refusal to help as “incredible.” As for the state police, they declined to interfere in a federal matter.

“We beg that the authorities help us… we do not want the luck of Aguililla, but we’re close to that point,” Martínez said.

With reports from El Universal