I went to the south of Mexico to meet migrants and cover their struggles on their northward journeys, but I never envisioned I’d become one.

Traveling back from a town to Tapachula, Chiapas, on October 3, the minibus I was in was stopped by immigration officials at a checkpoint. I soon realized the highway was littered with such checkpoints, stationed with heavily armed soldiers.

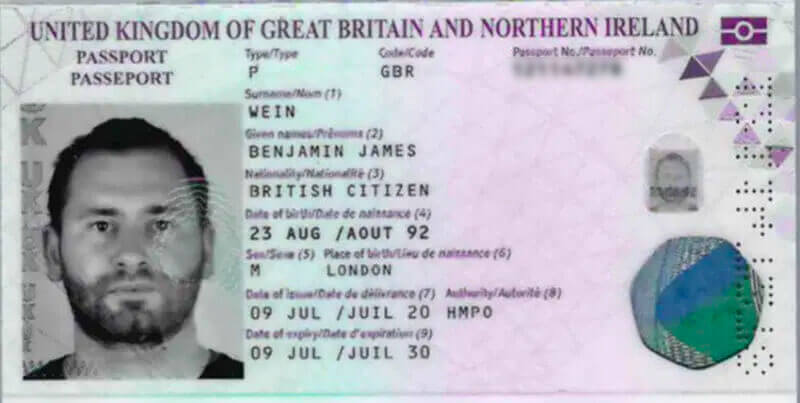

An immigration official asked to see my passport. I didn’t have it, but offered a UK driving license. Insufficient.

I would be taken to the immigration office in Tapachula where my legal status in the country would be verified, the officials said.

Before long, myself and a Honduran migrant, Marlon, were loaded onto a bus with about 30 Haitian migrants. We arrived at the “21st Century” migrant detention center nervous and confused. What happened next offered no remedy.

Belts off, shoelaces off, was the order. That was the moment it dawned on me where I really was. Amid a heavy police presence our phones and money were confiscated.

We were led into a section full of what can only be described as inmates and told to pick up a mattress and find some space on the floor. A heavy metal door with a small barred window was locked behind us. Federal police officers guarded the door in case anyone thought of escaping.

Tensions were high: this wasn’t the kind of place where you wanted to be a newbie.

It had a strong smell of male sweat due to the presence of about 130 men who had bigger problems than personal hygiene. I was never told the maximum capacity of the hall, despite asking repeatedly, but would guess about 40.

There was barely space to move; the hallway was flooded with mattresses and defeated expressions. Our section of “21st Century” offered a mess hall, which we were told might be the best place to find a spot on the floor; showers; two televisions blasting out Mexican programming; non-flush toilets short of doors, and an exercise yard with a concrete football pitch and a police watchtower.

No food was available that night. I spoke with Marlon and two migrants from El Salvador before finding a safe looking space in the corner, and attempting sleep.

I woke to discover the exercise yard and wandered out to see something unexpected. An Indian boy, legs crossed, hands clasped, praying to the Hindu god Shiva. He was one of five Indians inside who had traveled to South America and trekked across the Darien Gap, an inhospitable and dangerous area where Colombia’s border meets Central America.

Some Venezuelan and Colombian inmates had crossed it too. Other African detainees from Ghana, Burkino Faso and Senegal also knew the Darien Gap first hand. Many of that African contingent could be seen engaged in Islamic prayer throughout the course of the day.

However, those nationalities were in a minority. A large proportion of the migrants were from Haiti, many of whom only spoke French Creole. A handful spoke Spanish, having lived in Chile, and some others spoke Portuguese due to their years in Brazil.

Central Americans were the other major population, from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua. A smattering of Cubans and a lone Peruvian completed the list.

Wherever they were from, when I explained my story and my nationality I was met with a mixture of bemusement and hilarity from police included, who found the situation hugely amusing. Sympathy was understandably in short supply, my case seemed resolvable. Some others had been inside for more than three months.

At one point I battled my way to make a phone call and rang the owner of my hotel in Tapachula to plead that she deliver my passport to the detention center. I presumed once I could present my passport entry stamp and immigration form I would be released. That turned out to be false.

My documents, I was told, would have to be verified in a laboratory in Mexico City. It was now apparently a question of proving my innocence rather than my guilt, contrary to basic legal principles. However, there was actually no legal complaint against me. Like the other immigrants I was in a legal black hole. We hadn’t been arrested. In fact, according to immigration officials and Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard, we had been “rescued.” In reality, we had been taken hostage.

The destination for everyone inside, except for myself, was the United States. Many were applying for refugee status in Mexico through the refugee agency Comar as a means to that end. They were detained, wrongly they believed, even after making their application. Others were released and ordered to leave the country by the nearest border within 20 days.

It turned out, however, that the American Dream was a hard one to extinguish, and almost all of the migrants, whatever their legal situation, were determined to make it to the U.S.A.

Rumours abounded that the U.S. government was paying Mexico per head for every would-be migrant it detained. I wondered if that price were per migrant, or per migrant per night, and if we were being kept in for long spells as a money-making exercise.

Sleep was scarce and nutrition was poor. Amid poor hygiene and the sheer quantity of people inside, diseases were spreading. More people were coughing each day. Immigration officials denied that the COVID-19 pandemic could breach the walls of the detention center: “There is no COVID,” one official told me.

I would repeatedly beat on the metal door demanding immigration officials attend to the section, provoking the police on the other side, while being wary not to push them too far. My assumption was that immigration officials were legally bound to be in attendance 24 hours a day, but we once went for 20 hours without as much as a visit.

The days passed waiting for meal times, feeling enraged and hearing tales of migration. That said, there was fun to be had too. The boisterousness of 130 guys who had lost all respect for authority made for some pleasing Tom and Jerry style runarounds.

What might surprise people is how little violence there was at “21st Century,” odd scuffles aside. Although there were certainly violent criminals among us — some admitted as much — no one wanted to land themselves in hot water. The police remained calm as a generality, and ignored provocations. The immigration officials were masters of disinterest. It was negligence more than anything, astounding in its plenty, that put inmates at risk.

Eventually, at about 11:00 p.m. on October 7, my name was read from a list. By that time I’d got to know almost everyone inside, and had become well liked. I felt sad to leave behind those in more desperate situations than mine.

What I didn’t know is that someone had been fighting for my freedom from outside. By her own intuition she had managed to get in touch with the head of immigration in Chiapas, which seems to have prompted my release.

I waved and shouted “good luck” to the inmates who were lying down for another night on the floor.

As I was led out of the facility and tasted fresh air, for the first time in my life I knew the value of freedom. I celebrated it with a whisky in the first bar I found.

Mexico News Daily