The federal government’s non-confrontational security strategy that purports to address the root causes of violence through the delivery of social programs is a failure and a “tremendous, historic error,” according to a former vice president of Colombia.

Francisco Santos Calderón, a journalist, former ambassador to the United States and vice president during the 2002-10 government led by conservative president Álvaro Uribe, has been in Mexico for the past month and spoke with the newspaper El Universal.

Asked how he would describe President López Obrador’s so-called abrazos, no balazos (hugs, not bullets) security strategy, Santos responded:

“As a failure and a tremendous error – a historic error that Mexico will pay for during many decades … [with] many more deaths, a greater penetration of drug trafficking in society and political power, and a much more narcotized society.”

Santos, cousin and outspoken critic of former Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos, asserted that the federal government’s security strategy has already caused homicide numbers to increase.

(López Obrador’s first full year in office – 2019 – was the most violent year on record, but homicides declined slightly in 2020 and were down 3.8% in the first 11 months of 2021 compared to the same period of the previous year.)

“What abrazos, no balazos does is encourage crime [groups] to be much more aggressive. Small crime groups and medium-sized crime groups grow, and they’re the ones that generate large amounts of violence, … they’re hyper-violent … because they have to face up to large organized crime [groups]. This is the worst policy that one could establish and you are living it,” the ex-vice president said.

Santos also said that Mexican cartels are now working much more closely with Colombian cartels than was previously the case.

However, he opined that the former are “much more powerful” than the latter and are consequently able to exert influence over them. “[Mexican cartels] are the main buyers of their product [cocaine] and work hand in hand with them,” Santos said.

Drawing on his knowledge of the situation in Colombia, he charged that rebuilding “combat structures” dismantled by the current Mexican government will be extremely difficult, although López Obrador has continued to use the armed forces for public security tasks.

Juan Manuel Santos dismantled “the entire apparatus” for fighting drug cartels during his 2010-18 presidency and current President Iván Duque hasn’t been able to rebuild it since he took office in August 2018, Santos said.

“… Rebuilding an entire apparatus has been tremendously difficult because the mafias tend to consolidate, they become much more powerful. … For the state to build an apparatus capable of … neutralizing these organizations takes a lot of time, and I say it from the experience I’ve seen in Colombia between 2018 and 2022,” he said.

Asked whether using the armed forces to combat organized crime was a good thing, Santos responded:

“No, the armed forces are for territorial control … It must be trained police forces … with a lot of internal control, a lot of counter-intelligence. The fight against criminality is a police, intelligence and justice issue. Using military force in that is a mistake.”

Members of Mexico’s municipal and state police forces are generally poorly trained and badly paid, making them more likely to collude with organized crime. The federal government disbanded the Federal Police and created a new, quasi-militarized police force, the National Guard, but it has failed to reduce violence by any significant amount.

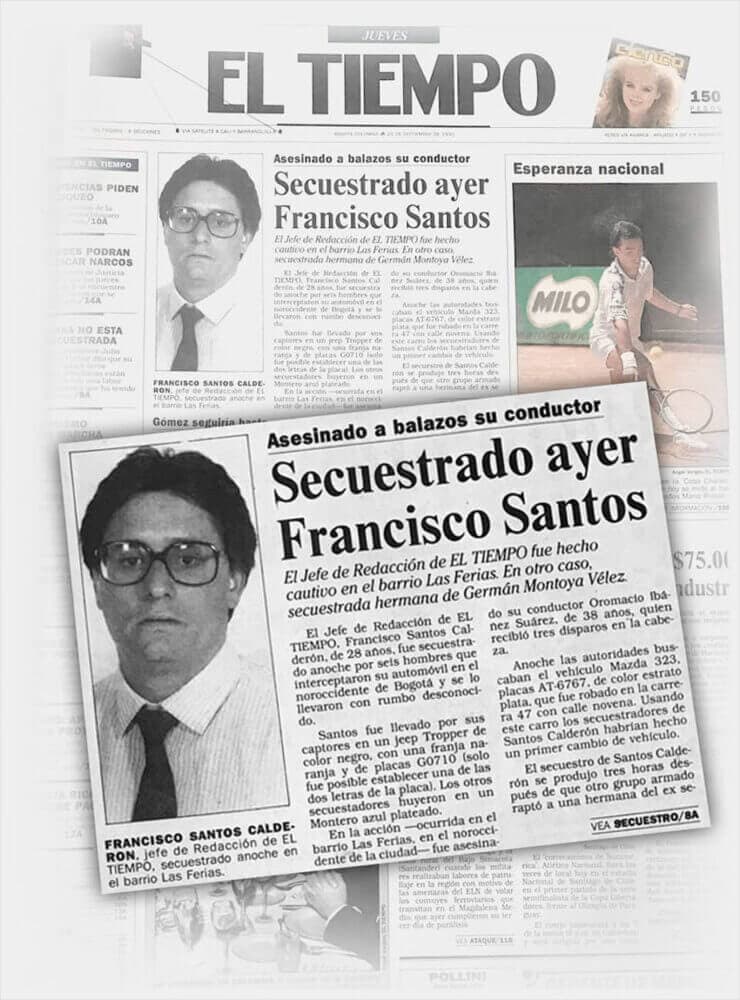

Santos, who was kidnapped by the Medellín Cartel when he was working as a newspaper editor in 1990, also criticized López Obrador for not being a greater defender of democratic values in Latin America, where Russia “is more active … than during the Cold War” and China is starting to exert its “economic power and political power of interference.”

“[Mexico] should be the great leader in the defense of democracy, it should be the great leader of … [democratic] values, but it’s not doing it precisely because in Mexico at this time there is a president who is very inward-looking and whose values are … [aligned] with leftist totalitarian values, … freedoms are not part of his values, and Mexico is missing out on the great opportunity it could have to become the icon of freedoms in the continent,” he said.

“Andrés Manuel López Obrador isn’t interested in that,” Santos said before asserting that the Mexican president is a fan of current and past leftist Latin America leaders such as Hugo Chávez, Daniel Ortega and Evo Morales.

“… It should be the opposite, [Mexico] should become an epicenter of … policy in defense of freedom and democracy in Latin America,” he said.

With reports from El Universal