The streets of the market in the Mexico City pueblo of San Gregorio Atlapulco, normally filled with street vendors and people selling produce from wheelbarrows and small stands, are now empty after the Xochimilco government shut them down until at least August 2.

The small fruit and vegetable stores remain open but no baskets filled with produce sit in the streets like they usually do; everything has been pulled inside. The market itself, usually bustling, is eerily empty. The building’s walls are now plastered with posters, some warning about the dangers of the coronavirus, others encouraging people to wear masks and keep a safe distance.

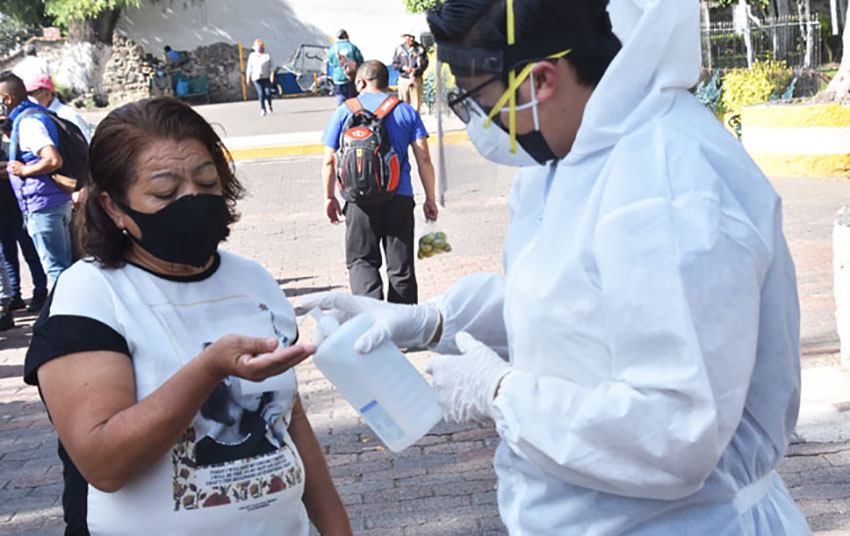

Last week, Xochimilco healthcare workers arrived. They’ve been walking through the market wearing white protective suits and armed with antibacterial gel to spray on people’s hands and others were spraying disinfectant on sidewalks and buildings. They’ve set up a tent behind the church to test people for the virus.

The federal government uses a stoplight system to indicate areas with high numbers of infections with red being the worst. If there were another color to indicate an even worse situation, San Gregorio might warrant it. That’s because the pueblo, with a population of about 30,000, has the highest number of infections out of 1,812 colonias, pueblos and barrios in Mexico City.

“We are handing out information,” said medical services assistant director Marisol Olivares. “We want to tell people what is happening.”

It’s good to finally get attention — and some action — from the municipal government. But sadly it has the feeling of too little, too late.

Back in March, when the pandemic was just getting underway, thousands of people crammed into the pueblo for the Fiesta de San Gregorio, a 10-day event marking the death of the pueblo’s patron saint. Streets in the center were lined with vendors, there were concerts every night and a huge fireworks display on the last night. Everything was well attended.

I photographed the the first day of the event — from a safe distance — and over the course of several days interviewed people about the pandemic. What I was almost always told was, “No pasa nada.” Nothing will happen.

Some people claimed it was because Chicuarotes (which is what people living here call themselves; it’s a local chile) are stronger than other people. Others said — only half jokingly — it was because Mexicans drink a lot of tequila.

No one wore a mask at the festival; no one practiced safe distancing. That attitude continued for months and we’re now paying the price.

One of the people I interviewed in March was Ábel Cortina, who owns a small store near the center of the pueblo. He was one of those who believed nothing would happen, that the pandemic was simply a rumor. He’s changed his opinion.

“I was wrong back in March,” he said. “We did not see the danger. We had our fiestas, we did not keep distance, we carried our saints in processions. We were wrong.” He now wears a mask and keeps a bottle of antibacterial gel on the store’s front counter.

At one of the last Catholic Masses in late March, before all church activity was suspended and the church locked up, Padre Arturo, the parish priest, told his parishioners that they would be protected by the pueblo’s patron saint. Legend has it that in 590, San Gregorio stopped another plague by organizing prayer vigils and processions.

“[Padre Arturo] said we must entrust ourselves to San Gregorio,” Octavio Flores said in early April when I spoke to him, “In the same way that he saved his people from the plague he will save us from the coronavirus.”

The 15-year-old Flores is a member of “Los Varones,” an organization of 14 young men who dedicate a year or more to serving the church. “I believe San Gregorio will protect us, certainly,” he said at that time. “I do not use a mask or gloves because my faith will protect me.”

It’s anyone’s guess how many people fell ill because of their faith in the saint but Flores is healthy and now wears a mask when he goes out. “The hope that San Gregorio would protect us from the pandemic has failed.” He said his faith is still strong but “Now we have to protect ourselves.”

Unfortunately, not everyone has caught onto that.

Until the municipal government banned street vendors, Nazario Fernández Landero sold pots and pans on Calle Insurgentes. The day I met him, he wasn’t wearing a mask. “I was in a rush this morning,” he said, “and forgot it.” When asked if he was afraid to be without a mask, he pointed one finger to the sky. “I am not afraid,” he said. “If God says he will take me, he will take me.”

He’s not the only one who believes this and, for whatever reason, there are still people congregating without masks.

Mexico City’s Central de Abasto is the world’s largest market and it’s estimated that between 300,000 and 400,000 people pass through there in a single day. So it’s no surprise that it’s a major center for the viral outbreak. Many Chicuarotes sell their produce in the market or work there and it’s believed that they were among those who brought the virus to the pueblo. In fact, many people who work there have become sick and some have died.

Juan Serralde grows vegetables in the agricultural area known as the chinampería and every Sunday delivers his produce to the Central de Abasto. “I do not sell there, only deliver five or six boxes,” he said. He takes many precautions, including wearing a mask, gloves and spraying himself with disinfectant. He’s still afraid but feels he has no choice. “I go to the city for necessity, to provide for my family. We have to keep working because there is nothing else.”

The Clinica Médica Isabel is a tiny clinic in the pueblo that can’t treat people with Covid-19 symptoms. When someone arrives with symptoms, they’re sent to a hospital but some refuse to go. “People are afraid to go to the hospital,” said Domingo García Flores, the clinic’s administrator. “In fact, they believe that doctors want to kill them.” So they quarantine at home, putting others at risk.

There’s no doubt that, in some ways, things have improved. The majority of people are wearing masks, fist bumps and elbow taps have replaced handshakes and hugs, most stores have antibacterial gel available. But there are those who are out and about without masks and social distancing in the market, despite there being fewer people, is still not practiced.

Olivares, the assistant director of medical services, said healthcare workers will be coming to the pueblo daily for at least another two weeks. “We are bringing doctors and nurses. We are trying to educate people,” she said.

But, she added, “People still do not listen.”

Joseph Sorrentino lives in San Gregorio Atlapulco and is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.