A recent study of ancient DNA from pre-Hispanic populations uncovered evidence that some Indigenous groups adapted to climate change-induced droughts, rather than migrating.

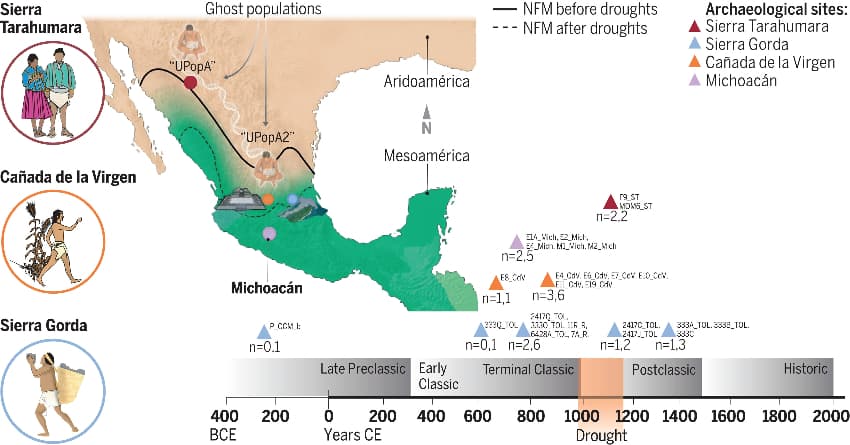

In a research article published Friday in Science, the authors explain that before the Spanish conquest, Mexico was divided into Aridoamerica in the north and Mesoamerica in the south. In Aridoamerica, pre-Hispanic groups subsisted on hunting and gathering, while agriculture was the primary subsistence activity in the south. The line dividing them, which shifted over time, has long been the subject of study.

The dominant theory, based on a series of anthropological studies, has been that Indigenous groups inhabiting the frontier of Mesoamerica were forced to migrate south due to drastic climate change events that occurred around 1,000 years ago, causing the border with Aridoamerica to shift south as the Mesoamerican population was replaced by hunter-gatherers from the north.

However, a study of ancient DNA carried out by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in conjunction with academic institutions in Europe and the U.S. contradicts these claims. New evidence suggests that some pre-Hispanic peoples did not move during the drought, but instead adapted to the lack of water and adopted new livelihoods.

The study is one of the largest ever of Mexico’s ancient Indigenous peoples.

The researchers analyzed 27 genetic samples from pre-Hispanic individuals, taken from eight archaeological sites in the Sierra Gorda region of central Mexico and the northern border of Mesoamerica. Their findings suggest that the population that inhabited the region did not migrate during the period of extreme drought that occurred between 900 and 1,300 A.D.

“Individuals from Sierra Gorda before and after the drought shared a greater genetic affinity with each other than with any other pre-Hispanic individual,” researchers said.

One of the researchers, María Ávila-Arcos, from UNAM, explained in an interview with newspaper El País that while droughts caused other populations to migrate, this does not appear to be the case for the groups that inhabited the Sierra Gorda.

“In the site we studied, population replacement did not occur. Continuity was reflected,” she said.

This genetic continuity extends to the modern Indigenous population, according to the study.

A possible explanation for this “is that the favorable climatic conditions in the north of Sierra Gorda have maintained higher humidity than other arid places on the northern border of Mesoamerica.”

Researchers also believe that the inhabitants of the Sierra Gorda survived due to their involvement in cinnabar mining as a primary subsistence activity, rather than a dependence on agriculture. Cinnabar is a mineral that had sacred value throughout pre-Hispanic times.

Still, the researchers acknowledge, there are also factors that suggest inhabitants could have indeed suffered a strong population decline due to climate change. The study ultimately demonstrates that the migratory movements of ancient Mexican civilizations were more complex than previously believed.

Their research also shows the degree to which DNA among Mesoamerican peoples was linked. Scientists found continuity between the Pericúes, an Indigenous group from the Baja California peninsula that disappeared in the 18th century, and the Pima people (also known as the Akimel O’odham), who currently live in Arizona, Sonora and Chihuahua.

The researchers also identified two unsampled ancient “ghost” populations that genetically contributed to pre-Hispanic populations in northern and central Mexico. This discovery raises questions about demographic events that may have given rise to the Aridoamerican and Mesoamerican populations.

“There are more questions than answers,” Ávila-Arcos said. “What [the study] does let us see is that the process behind the population of America was quite complex.”

With reports from El Pais and La Vanguardia