The federal government said Thursday that it has definitively established the whereabouts of 15% of more than 110,000 people who were listed on its missing persons register in late August.

At President López Obrador’s regular press conference on Thursday, Interior Minister Luisa María Alcalde announced the results of a “massive” nationwide search for missing persons that was carried out as part of the government’s “National Generalized Search Strategy for Missing Persons,” which is commonly referred to as a missing persons “census.”

She explained that “search brigades” were formed in all 32 of Mexico’s federal entities, and that their almost 5,000 members completed over 111,000 visits to homes where it was believed missing people might be living based on information derived from numerous government databases.

In addition to visiting homes, search brigade members made over 86,000 telephone calls to inquire about the whereabouts of missing people, the interior minister said.

“What are the results of this effort? The location of 16,681 people. In other words, in these 16,681 [missing person cases] we are certain of their whereabouts,” Alcalde said.

She said that 3,945 people registered as missing were located in their homes, while 4,134 were found to have died. Alcalde said that 197 people registered as missing were found in prisons across Mexico, while local authorities informed the federal government that 8,405 people had already been located.

The combined total of 16,681 located persons represents 15% of the 110,964 people who were registered as missing on Aug. 22.

The interior minister said that the government had managed to “place” an additional 17,843 people registered as missing, but hasn’t been able to locate them. That figure represents 16% of the total number of registered missing persons in late August.

“We’ve found [those people] in databases, but we don’t yet have proof of life because we haven’t been able to find them face to face,” Alcalde said.

She gave an example of the kind of thing she was talking about.

“Nayeli” was reported as missing in February 2014 when she was 13 years old, “but we’ve found her in more than seven databases,” Alcalde said.

She said it was detected that the young woman became a beneficiary of the government’s Liconsa milk distribution scheme in 2019 and enrolled in an adult education program the same year.

In 2020, “she entered the Quintana Roo health system,” while in 2021 she “obtained a middle school certificate,” Alcalde said, adding that the government had also found that Nayeli had been vaccinated against COVID, found employment in the Youths Building the Future apprenticeship scheme and, in 2022, updated her registration with the SAT tax authority.

“We’ve tried to find her, we visited her [supposed] address in Quintana Roo, then in Campeche, but we haven’t had success,” said the interior minister, who didn’t mention the possibility that another person, or other people, had used Nayeli’s name and other personal details.

The interior minister outlined a similar scenario involving a man who disappeared at the age of 25 in 2013.

Alcalde also spoke about cases involving supposedly missing people who had been definitively located by the search brigades. Among them was a woman who the interior minister said was kidnapped in 2019 but released the next day.

“We found her in her home in Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua,” Alcalde said.

“… We have other cases … [of people] we found in penitentiaries,” she said before citing former cartel leader Miguel “Z-40” Treviño Morales as an example.

“Z-40 was in the databases as missing, but we all know that this person is shut away in one of the high-security prisons,” Alcalde said.

López Obrador has previously asserted that Mexico’s missing persons register isn’t accurate, and advocated a new count.

He said in August that Karla Quintana’s resignation as head of Mexico’s National Search Commission (CNB) may have been “because of the census,” which has been conducted by so-called “servants of the nation” – government officials who have mainly aided the implementation of social programs – and others.

After presenting data on the people that have been found and “placed” by the search brigades, Alcalde told the president’s press conference that there was “insufficient data to identify” 24% of the people registered as missing in late August. An additional 32% of people officially classified as missing – some of whom disappeared decades ago – are identified, “but we don’t have enough clues to be able to do some kind of search,” she said.

“Finally, 12,377 [people], which is 11% [of the register], are confirmed as missing,” Alcalde said.

She added that there were 1,951 “duplicate registrations” on the government register,

Quintana, who became CNB chief shortly after López Obrador took office in late 2018, claimed in November that the aim of the missing persons census was to reduce the number of people listed as such across Mexico, and especially in states governed by the ruling Morena party.

Non-government organization, search collectives and academics have also been critical of the census, warning that the government could be seeking to reduce the number of people officially listed as missing for electoral purposes.

However, the number of people on the register has actually increased since the national search strategy, or census, began. On Thursday, 113,322 people were classified as missing, according to a register dashboard on a Ministry of the Interior/CNB website. That indicates that people are disappearing and thus being added to the missing persons register at a faster rate than they are being located and removed.

Alcalde said Thursday that there has been a “campaign with lies” in which government critics have asserted that it was seeking to “remove missing people” from the register.

“We are not eliminating missing people” from the register, she asserted, adding that the government has been focused on searching and locating such people.

While Alcalde portrayed the government’s search strategy as a success, the El País newspaper reported last week that “a missing person was three times more likely to be found” before the new federal plan took effect in May.

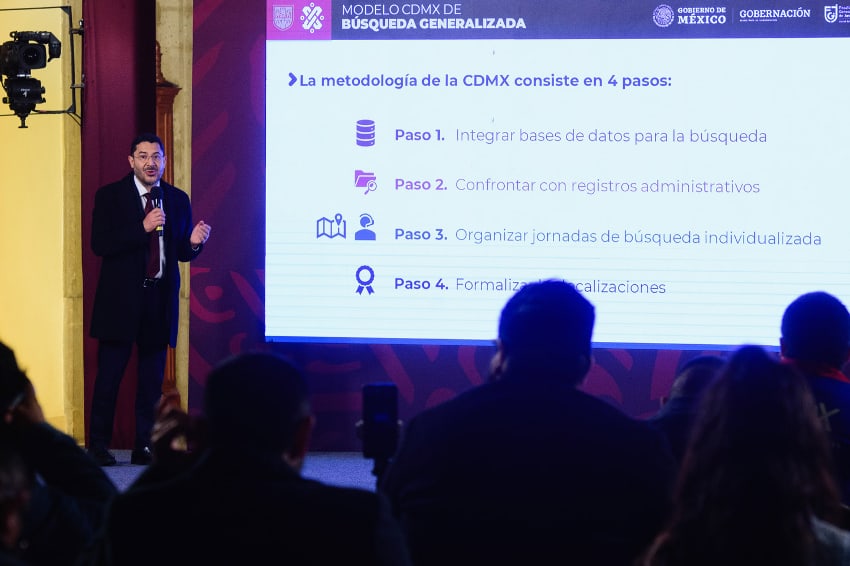

Kidnapping has been, and remains, a problem in Mexico, but data presented by Mexico City Mayor Martí Batres at Thursday’s presidential press conference showed that abduction – which in some cases precedes murder – and other crimes were only responsible for 6.8% of “historical” disappearances in the capital.

“Voluntary absence” and “voluntary absence due to personal problems” were the causes of disappearance in over 80% of missing person cases, while mental illness and accidents were factors in 7.8% and 3.1% of cases, respectively, according to the Mexico City data presented by the mayor.

With reports from Aristegui Noticias