For some indigenous children in Oaxaca, lack of a television or internet is not the only barrier to learning: language is as well.

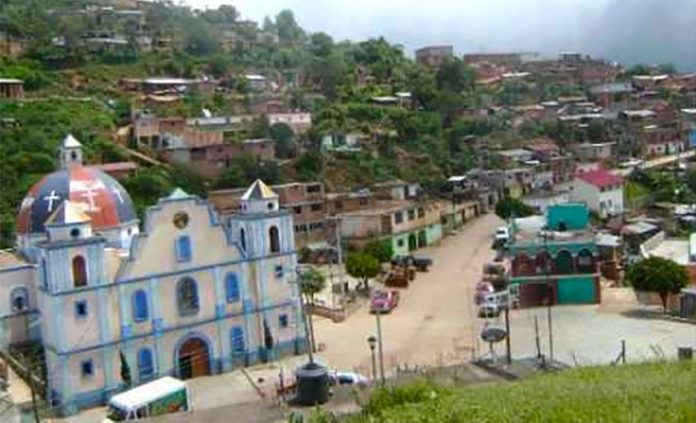

Rosalva Sánchez Soriano teaches at a school in San Juan Quiahije, where most residents speak Chatino rather than Spanish. This includes the 22 students in her care this school year who are learning Spanish as well as adapting to distance learning in a community where most don’t own a television, much less have access to a computer or an internet connection.

In order to meet her students’ needs, Sánchez has adopted a different strategy than that which the federal government has put forward.

Instead of starting the school year on August 24, her students will begin classes on September 7, and they won’t be doing so in front of a television or computer monitor.

Instead, Sánchez will print out lessons in the Chatino language each week and leave the booklets for students to pick up at the town’s only cybercafe.

The Ministry of Public Education’s (SEP) solution to the coronavirus pandemic is simply not viable for many students in poor, mainly indigenous communities, she says.

“Yesterday I was watching a transmission and the truth is that it is difficult for children in primary school and rural areas, who speak 80% in their mother tongue and 20% in Spanish, to understand,” Sánchez explained. She doesn’t fault the federal government’s distance learning plan given the circumstances created by the pandemic, but it is not going to help students like hers get an effective education.

The SEP says there are 1.2 million indigenous students in Mexico, mainly in Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla and Veracruz. The most widely spoken languages are Náhuatl, Mayan and Tzeltal.

An estimated 45,000 people in southern Oaxaca speak Chatino, and although the federal government has translated lessons into 24 different indigenous languages of the 68 spoken in Mexico, Chatino is not one of them.

Source: Reforma (sp)