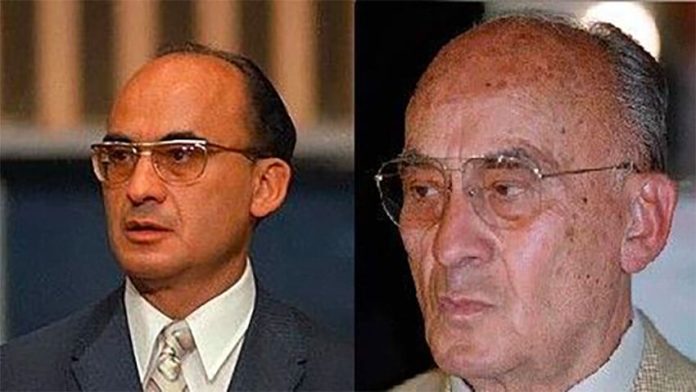

Luis Echeverría, a controversial and widely-despised president who ruled Mexico during the country’s “dirty war,” turns 100 on Monday, becoming the first Mexican president to reach triple figures.

President for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) from 1970 to 1976 and interior minister for seven years before that, Echeverría was born in Mexico City on January 17, 1922.

The bespectacled former leader, who now lives in Cuernavaca, planned to mark Monday’s milestone with a celebration on video conferencing platform Zoom with approximately 30 friends, family members and former collaborators, the newspaper Reforma reported.

Echeverría, born less than two years after the end of the Mexican Revolution, studied law at university and started working for the PRI – Mexico’s once omnipotent party – in 1946. He was a deputy interior minister by the late 1950s and became interior minister at the tail end of Adolfo López Mateos’ 1958-64 presidency.

Echeverría stayed on as interior minister when Gustavo Díaz Ordaz assumed the presidency in late 1964 and remained in the position until November 1969.

His position in the Díaz government – interior minister is generally considered Mexico’s second highest office – implicated him in the 1968 massacre of students in the Mexico City neighborhood of Tlatelolco, perpetrated by the armed forces just 10 days before the start of the Summer Olympics in the Mexican capital.

The massacre, in which an estimated 350 to 400 students were killed, is considered part of the Mexican Dirty War, an internal conflict from the 1960s to the 1980s in which successive PRI governments violently repressed left-wing student and guerrilla groups.

State-sponsored violence continued with Echeverría at the helm of the federal government, most notably with the 1971 Corpus Christi massacre in Mexico City, briefly depicted in the award-winning 2018 film Roma.

An estimated 100 to 200 students, some in their early teens, were killed in the massacre known as El Halconazo, or the Hawk Strike, because it was perpetrated by a government-trained paramilitary group called Los Halcones.

Echeverría attempted to distance himself from the violence and enforced disappearances that marked both Díaz’s government and his own administration, but he was unable to escape the attention of a special prosecutor’s office established during the 2000-2006 Vicente Fox presidency to investigate violence perpetrated by the state in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

The ex-president was summoned to give evidence in 2002, formally accused of genocide and a warrant for his arrest was issued.

But Echeverría obtained an injunction against the arrest order and was never taken into custody. He did, however, spend a period under house arrest before being exonerated of genocide charges related to the Tlatelolco massacre in 2009.

Despite his advanced age, activists are still seeking to hold the ex-president to account for his alleged crimes against humanity.

The centenarian, who served as ambassador to Australia in the late 1970s, was last seen in public last year when he was taken in a wheelchair to the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City to get a COVID-19 vaccine shot.

As president, he ruled Mexico with a style of populism similar to that employed by Lázaro Cárdenas, Alexander Aviña, a historian, told the newspaper El País.

Cárdenas, president from 1934 to 1940, is best remembered for nationalizing Mexico’s oil industry and, unlike Echeverría, a beloved Mexican president.

During the campaign leading up to the 1970 presidential election, Echeverría “traveled the whole country to meet different communities wearing his guayabera [shirt],” said Aviña, a historian of Mexico and Latin America at Arizona State University.

“When he attained the presidency he formulated a populism of the Cárdenas style. He knew there were various crises. He had been interior minister and he tried to operate with a populist profile in the domestic sphere,” he said.

One of Echeverría’s central objectives, the newspaper El Financiero reported, was the equitable distribution of wealth.

As part of his governance model, he increased spending on infrastructure, created dozens of public trusts and state-owned companies, expanded agricultural and fishing subsidies and provided additional support for the nation’s poor, the newspaper said.

Echeverría also styled himself as a leader of the third world, championing the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, which was approved by the United Nations General Assembly in 1974.

Diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China were formalized during his presidency and he strengthened ties with Chile, which was led by leftist Salvador Allende during the first half of his six-year term. After Allende was ousted in a military coup and replaced by Augusto Pinochet in 1973, Echevarría opened Mexico’s doors to Chileans persecuted by the Pinochet regime, even as he persecuted Mexican leftists at home.

Echeverría ran into economic problems such as high inflation and growing foreign debt in the second half of his six-year term, and reforms he pursued didn’t endear him to the population as much as he had hoped.

Meanwhile, his government’s authoritarian tendencies meant he was public enemy No. 1 for some sectors of the population, especially students for whom the Tlatelolco and Corpus Christi massacres were recent memories or even lived experiences. The business community dubbed him a communist for his wealth redistribution efforts and largesse toward the poor.

More than 45 years after he left office, Echeverría remains a controversial and much-loathed figure. Few Mexicans were game to publicly congratulate him on reaching the august age of 100. Many, however, took to social media to condemn the erstwhile president.

Aviña, the historian, denounced the ex-ruler in a Twitter post. “Former Mexican president and butcher of popular movements Luis Echeverría turns 100 today, free and still enjoying the impunity that shields him from prosecution,” he wrote.

“… He’s the world’s oldest genocide perpetrator and a living nightmare for his victims,” said Adela Cedillo, a University of Houston historian. “… His legacy of violence and corruption has marked all of us,” she wrote on Twitter.

“There are many contemporary problems that began in Echeverría’s six-year term but without a doubt his most lasting legacy is state violence,” Cedillo told the news agency EFE.

With reports from El País, El Financiero, Aristegui Noticias and Reforma