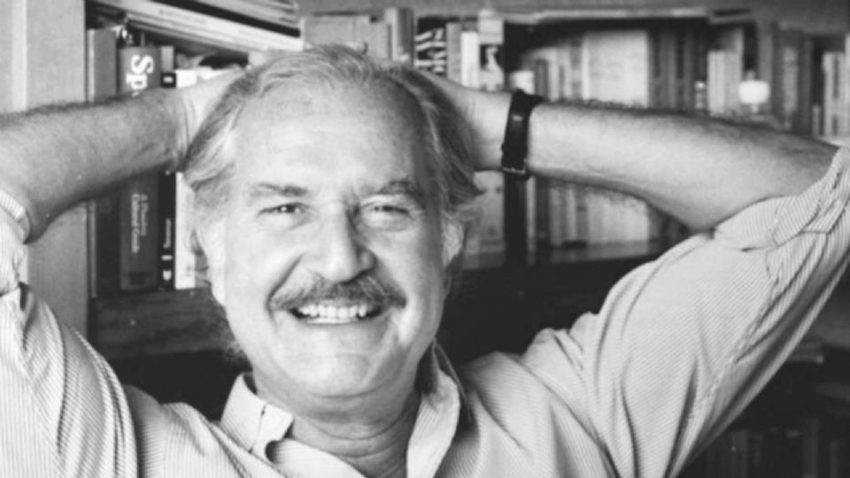

Mexican author Carlos Fuentes entered my life with the soft insistence of a truth you

recognize before you can name it. In a house where books functioned as liturgy and

political arguments were my family’s daily prayer, politics and fiction braided until

nationhood itself could only be discussed through story. Friends learned to avoid politics

and religion in polite conversation. But at our table, it was compulsory.

Encountering Fuentes

Between my mother’s journalistic and analytic perception and my father’s artistic view of the world, I first encountered Fuentes. It was an introduction that felt less like discovery than initiation. I first found “The Death of Artemio Cruz” rummaging through my parents’ bookshelves as a teenager, that furtive, holy act of taking what the house has to offer. The book is a slow, terrible confession. It follows a revolutionary soldier who becomes a wealthy

businessman and, on his deathbed, confronts the compromises that made his life

possible.

I asked my father if I might read it. He agreed with the tolerant risk of someone

who knows the power of literature. I was too young to understand everything — too

young for many of the dates and alliances and the dense historical scaffolding — but not

too young for the voices. The blunt honesty of Fuentes’s interlocutors cut into me. Their

phrases echoed family stories, private grievances and the way a father’s silence sometimes

explained more than his sermons. I went to sleep that night with the book heavy under

my pillow, feeling the first tremor of an allegiance.

Fuentes liked to say that the Latin American novel rescues what official history neglects.

It is an attractive aphorism: literature as a salvage operation, novels as lifeboats ferrying

the lives, rumors and embarrassments that governments prefer to let sink. But his claim

is more than rhetoric. Read Fuentes and you find not an inventory of facts but a map of

forces — the informal routines, petty calculations and generational betrayals — through which Mexican politics actually works. He is not interested in vindicating every detail of the

public record. He excavates the subterranean arithmetic of power. The small acts and

grand illusions that produce regimes.

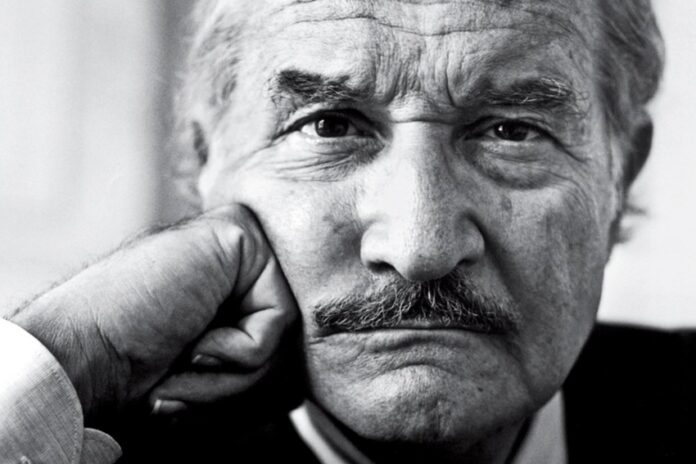

A gypsy in a black tie

If Fuentes’s vantage feels panoramic, it is because it was cultivated that way. Born in

1928 in Panama to a cultured, liberal diplomatic family, he spent his early years amid

the humid expanses of Montevideo and Rio de Janeiro. Those tropical afternoons — book-lined, humid and full of foreign tongues — were where Fuentes first fell in love with literature. Alfonso Reyes, the Mexican humanist and a central pillar of the country’s intellectual life, became an early mentor who guided him through the literary world. The young Fuentes absorbed European and Latin American canons with equal appetite, continued his journey to Washington with his family. They stayed eight years in the American capital amid tense Mexico–U.S. relations following President Lázaro Cárdenas’s 1938 nationalizations.

Distance sharpened his sense of Mexico as a nation, and of his identity as Mexican in a

foreign country, as he turned into a schoolyard enemy thanks to the “Tata Lázaro” initiative. Watching his country from abroad, he did not simply miss home. He began to interrogate it. He traced a family history animated by wider European convulsions — ancestors who fled Germany and Spain and settled in Veracruz, establishing a coffee hacienda, and he learned how much a personal identity could be a palimpsest of political choices and historical happenstance. Then a pivotal evening at a New York cinema, where he watched “Citizen Kane” with his father, supplied a kind of formal revelation: narrative could reveal the way private lives braided into public histories. He decided then to write within those intersections.

The acquisition of a global perspective

Fuentes’s early reading list — Stevenson, Dumas, Miguel Zévaco, Jules Verne — reads

less like a curriculum than a confession. He wanted plot and spectacle, but with an eye

to the moral and historical sediment underneath. A teenage posting in Chile broadened

that sensibility further. Latin American politics did not respect borders. The authoritarian

and reformist rhythms he observed in Chile and Argentina taught him that patterns

reverberated across the continent, that the fate of one republic often presaged the

anxieties of another.

He returned to Mexico, weary of the peripatetic diplomat’s life — the “gypsy in a black tie as he called it — and enrolled at UNAM to study law at Alfonso Reyes’s encouragement.

The law sharpened him. Fuentes would later borrow Stendhal’s praise for the

Napoleonic civil code — “clear, concise and effective” — and insist that legal training gave

a novelist a discipline of clarity. Yet his impulse was to use that clarity to break forms with

novels that could capture the messy simultaneity of Latin American time.

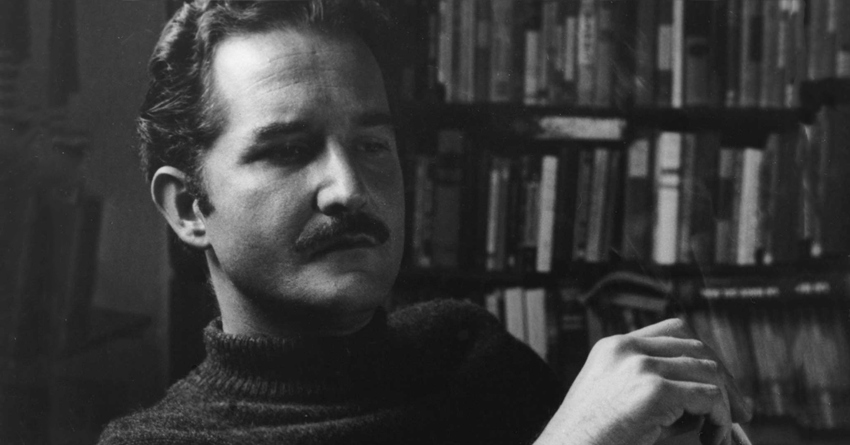

At age 26, he published his first book, “Los Días Enmascarados” (1954), a collection

where myth and the fantastic meet a restless modernity. His true breakthrough came

with “La Región Más Transparente” (1958), a book that announced, with a kind of civic

thunder, a new way of seeing Mexico City. From that moment, he was no longer an

apprentice. He was a national habit.

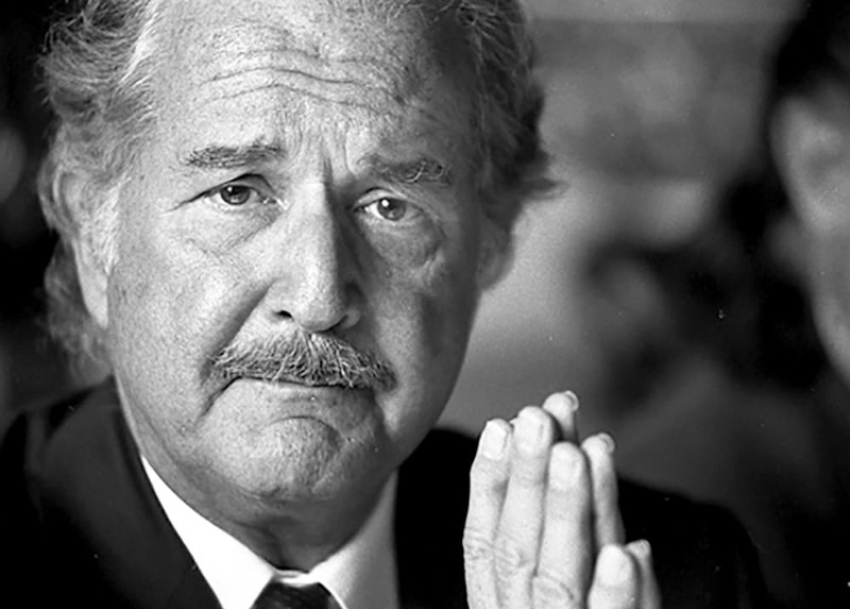

A life stranger than fiction

Fuentes’s public life was as complicated as his fiction. His unique voice made him

central to Mexican culture to the point where presidents listened carefully to what Fuentes

and other Mexican intellectuals had to say about their regimes. Later, he accepted the ambassadorship to France (1975–1977), a decision tied to a friendship with President Luis Echeverría that earned both praise and censure. When the following president, Gustavo Díaz Ordáz, took office, he resigned from his role as ambassador in protest to the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968, an act that marked him among writers who believed conscience could not be compartmentalized.

He would reflect on this episode as a reminder that the line between cultural influence and political entanglement is rarely neat. Fuentes moved within the circles of power even as he remained a most acute critic.

The restless writer

He was, by any measure, prolific, writing more than seventy books — including novels, essays, short stories, scripts and plays — along with a steady stream of articles across the Americas. Critics who catalog his work point to recurring obsessions: the mestizo nature of

Mexican identity, the ways power shifts under pressure, and, when left to its own inertia, the precariousness of state narratives that tidy over contradictions.

But to reduce Fuentes to a set of themes is to miss his artistry, which is the ability to render political life in the language of human habit: betrayal as domestic pattern, corruption as genealogy, revolution as a choreography of broken promises. If a reader wants a beginning, here are five texts that make his method and moral

urgency plain.

1. ‘La Región Más Transparente’ (‘The Most Transparent Region’), 1958

A portrait of Mexico City through a chorus of characters — peasants, intellectuals,

opportunists, dreamers — this novel critiques a hopeful bourgeoisie who believes

concentrated wealth will somehow be redistributed by fate. The city is staged as

myth and machinery, a place where pre-Hispanic ghosts brush against neon and

where national identity is debated in salons and tenements alike. Fuentes

anticipates the rupture generation’s disillusionments, sketching a metropolis both

magnet and mirror.

2. ‘La Silla del Águila’ (‘The Eagle’s Throne’), 2003

Set, proleptically, in 2020, told through letters after a communications collapse, it narrates a corrupt election, the corrosive compromises of those who seek higher office, and the blunt interventions of foreign powers — most pointedly the United States. It is less a

speculative thriller than a study in how institutions erode when informal networks

take precedence over civic duty.

3. ‘Tiempo Mexicano’ (‘Mexican Time’), 1971

An essayistic meditation on temporality and national memory. Fuentes argues that Mexican time is not linear but circular and overlapping. Epochs coexist and narrate one another. He examines who is given the right to remember and how state and culture conspire to shape

collective consciousness. Here, his faith in youth and his hope that new generations

could craft a more democratic nation glimmer most clearly.

4. ‘Nuevo Tiempo Mexicano’ (‘New Mexican Time’), 1994

Written in the wake of 1994’s ruptures — the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas and the peso’s collapse — this book is more sober. Where earlier essays were buoyed by the possibility of reform, “Nuevo Tiempo Mexicano” reflects on the hard limits of institution-building amid enduring inequality and the new economic realities shaped by NAFTA.

5. ‘El Espejo Enterrado’ (‘The Buried Mirror’), 1992

Perhaps my favorite, a sweeping cultural history that traces five centuries of Hispanic America. Fuentes is at once historian and storyteller. He narrates the persistence of colonial and Indigenous legacies as the subterranean currents of identity. The book is elegiac and

exuberant, a reminder that culture is not a surface polish but an accumulated

architecture.

Why read Fuentes?

Because he converts complexity into clearness without flattening it. He is not a historian

in the archival sense. Dates and citations are subordinated to moral geometry. But he

is remarkably precise in diagnosing how power, memory and myth conspire to produce

national life. His prose wants to unsettle complacency. He hoped readers would argue

with his books, not to annul them but to enlarge the conversation.

Fuentes belonged to an erudite generation that could look at Mexico from both inside

and outside. The diplomat’s gaze that knows protocol and the exile’s view that knows

perspective. He understood how the Mexican Revolution’s promise had been

domesticated: the postrevolutionary bourgeoisie reproducing pre-revolutionary

hierarchies, the PRI’s transformation from PRM into an apparatus that welded party to

state and how industrial growth often masked social exclusion.

Clarity and cultural insight

But perhaps his clearest insight is cultural. The Revolution’s deepest achievement was not the redistribution of land or the construction of institutions alone, but the knitting together of a fragmented populace so disparate communities could finally perceive one another.

To read Fuentes is to feel history as a kind of weather: sudden, changeable and always

shaping the small gestures of private life. His novels let you listen to Mexico’s

interiors — the whispered bargains, the private prayers and public betrayals. They teach

patience. Political truths are rarely delivered in headlines. They arrive through

accumulations of habit and choice, through the intimate narratives that novels can, more

truthfully than manifestos, deliver.

If you find a copy of his work, take it. Fuentes will not hand you a neat syllabus of

reform. Instead, he will offer scenes and voices that make the stakes of politics

unavoidable. His writing insists upon engagement. Not mere consumption, but

conversation – argument, indignation, laughter and, sometimes, renewal. In that

stubborn insistence lies his lasting invitation: to read Mexico not as a place to be

explained, but as a country alive with stories that refine what we think we know.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.