A lack of transparency in the federal government’s plans to build the 1,500-kilometer Maya Train through indigenous communities, world heritage sites and biosphere reserves in Mexico’s southeastern states has fuelled criticism that the views of the affected communities are being disregarded.

The government is under fire from academics, civil society and international organizations including human rights experts at the United Nations over its implementation of the project. The issues stem from a lack of information, leading to questions about whether or not due diligence has been carried out and why the findings are not being openly shared.

The government has claimed that the train will bring increased tourism, economic development and job opportunities and relieve pressure on crowded roads while offering a cheaper transportation option for commuters and businesses.

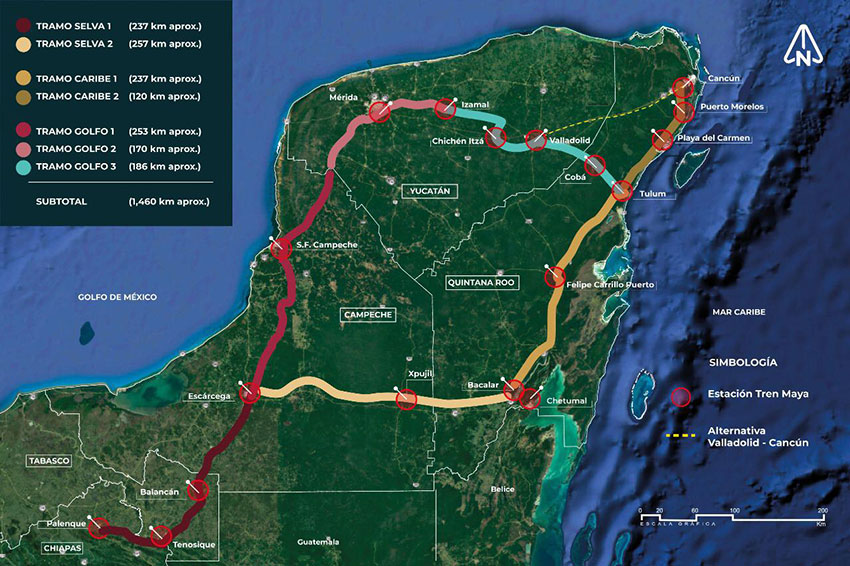

The train’s route runs through Chiapas, Yucatán, Quintana Roo, Campeche and Tabasco, all of which have many towns in need of investment after years of neglect by government. The project includes 18 stations and 12 development zones.

However, Giovanna Gasparello, a researcher at the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) and contributing author of a study on the social and territorial impact of the Maya Train, is concerned that there are no studies to show a link between the project and the development that has been forecast.

She rejects the government’s “neo-liberal argument that the free market will automatically bring benefits to the community,” suggesting instead that it should take responsibility for investment in the southeastern states instead of leaving it to market forces.

Back in November 2018, hundreds of academics wrote an open letter to President López Obrador (known colloquially as AMLO) to request detailed impact studies.

However, David Ordaz, media director at the National Tourism Promotion Fund (Fonatur), confirmed in December that no impact studies had been carried out for the project and the track that already exists [between Palenque and Valladolid] does not require one.

Gasparello disagrees with that position. She says the existing tracks are currently used by trains traveling at around 50 km/h to carry freight whereas the proposed passenger trains will travel at 160 km/h, and “therefore should be treated as a new project and analyzed in full.”

The government has commissioned some basic engineering studies, but it has not released the findings. On December 13, the day before consultation meetings began with indigenous communities, Fonatur held a press conference and announced that it had received the studies, but did not share their contents. It did not respond to repeated requests by Mexico News Daily to see a copy of the full report.

Meetings between the government and the academic community have not yielded any further information either. The National Institute of Anthropology and History invited Fonatur to a forum called “Maya Train: Realities and Myths” in the hope of opening a dialogue with the government. But the tourism development agency declined to disclose any additional studies or information, confirmed INAH’s Gasparello.

Furthermore, INAH’s requests for information from Infomex, the federal government’s transparency platform, have been denied on the grounds that the requested information has been classified for six years.

Where information is not regarded as classified, a review of the Infomex responses to Maya Train information requests shows a standard response: “After a detailed search in line with legal requirements, no documents were found.” This response was also given in December to a request for “any documents relating to the economic, technical, social, environmental and market aspects of the project or investment and finance reports.”

Authorities have stressed that the project will only go ahead if the people want it to: the consultation documents say “we decide together.” Government representatives at consultation meetings repeated the message, stating that the government will consider “second best options” in the event that a consensus cannot be reached.

But in September López Obrador declared that “come rain, thunder or lightning, the Maya Train will go ahead.”

For that reason some participants at the consultation meetings considered it a done deal.

Oscar Alarcha of the Miguel Allende ejido in Champotón, Campeche, said he “would not oppose the consultation as it would go ahead in any event, with or without the consent of the people.”

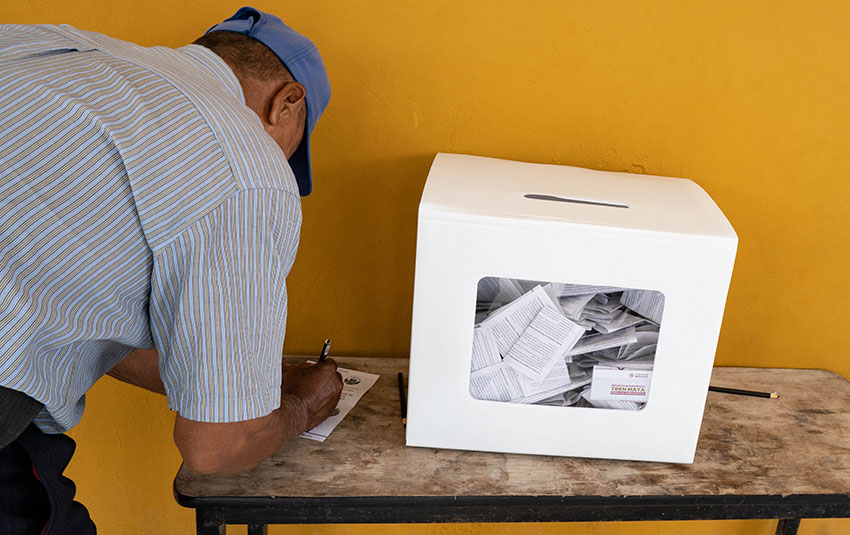

The consent was given regardless: the vote conducted following the consultations recorded a solid 92% in favor.

But the process has been criticized by numerous organizations, such as the Mexican Civil Council for Sustainable Forestry, for being an empty gesture with insufficient information and time to enable effective decision-making.

Gasparello’s research has shown that different communities received different levels of information throughout 2019. Nevertheless, the formal information stage of the consultation was not held until November with the consultation meetings in mid-December, leaving only two weeks to make a decision or raise objections.

The consultation was organized by the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI), a federal government agency. Spokeswoman Maritza Licona said information had been widely disseminated by way of the indigenous language radio stations, leaflets in various languages, meetings with community leaders and information meetings held at the end of November. Mexico News Daily requested a copy of those leaflets but INPI was unable to source a Spanish-language version.

Opponent Pedro Uc, who claims he received a death threat for his position on the train, considers the consultation meetings to be a government “trick” that only involved a selected part of the community.

Because the route passes through indigenous communities, the consultation process must satisfy the requirements of the International Labor Organization’s convention on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.

The Mexico office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (ONU-DH) has criticized the consultation process, saying it fell short of those international standards. The UN’s statement triggered an angry response by the Mexican government, which not only formally denied the accusation but also criticized the office for having “prejudiced any future relations, caused a climate of uncertainty and show[n] a lack of respect for the legitimate voluntary opinions expressed by the indigenous community.”

Despite the lack of detailed information, most of the participants in the consultation meetings were enthusiastic about the project’s possibilities, albeit without any evidence that the advantages would actually materialize.

A representative from Santa Cruz, Campeche, was excited about the potential for the train to “put my small community on the map.” He hopes the train will bring tourists to create a market for artisans’ handcrafts and “relieve the strain on the fishing industry” on which his people currently rely.

But another speaker questioned the government’s spending priorities. Oscar Alarcha of the Miguel Allende ejido asked that the government address healthcare, charging that services are expensive and people have to travel far to receive decent care. Local care is provided by “inexperienced” personnel, he said, and is not available seven days a week.

While opinion on the Maya Train is polarized, what is not in dispute is the need for investment in the southeastern states.

But the current practice of arbitrarily disseminating information to the media and local communities is only fuelling public cynicism and criticism rather than enabling a detailed and balanced consideration of the project.

Mexico News Daily