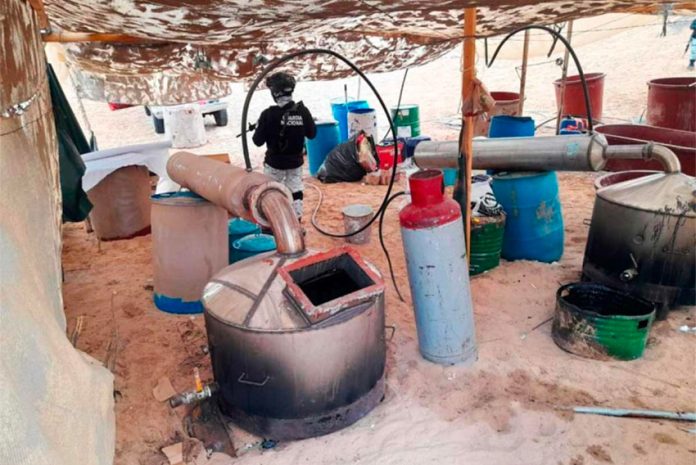

The Mexican marines carefully stacked the plastic drums one by one, dressed head to toe in white hazmat suits with gas masks tightly fastened around their faces to shield themselves from any toxic fumes.

Deep in the sierra of the state of Sinaloa, long the cradle of the country’s drug trade, authorities counted the solid crystal and liquid methamphetamine, precursor chemicals and equipment found at the clandestine lab.

On that Friday, August 17, 2018, security units in the air and on the ground had flanked the town of Alcoyonqui, nested into the surrounding mountains less than an hour east of the bustling state capital, Culiacán. Beneath the main production site, the mega-lab was outfitted with two underground warehouses to store some of the partially processed liquid methamphetamine.

In total, authorities seized at least 50 tonnes of methamphetamine and precursor chemicals used to produce the synthetic drug. It was the largest such seizure in the country’s history, evidence of just how much organized crime groups — in this case the Sinaloa Cartel — had ramped up production to feed growing demand for the drug in the United States.

The seizure was another sign of the spectacular rise of illegal synthetic drugs, in particular the stimulant methamphetamine and the synthetic opioid fentanyl. The spike in production in Mexico and use in the United States has coincided with a similar spike in Mexican use, particularly of methamphetamine.

Mass production has led to drastically lower prices in both countries, and methamphetamine use now rivals other commonly consumed drugs in Mexico like marijuana.

From US to Mexico production

It wasn’t always this way. Until the early 2000s, most of the methamphetamine consumed in the United States was produced in domestic laboratories, either tucked away in quiet suburbs outside of major cities or in rural communities. But by the 1990s and 2000s, mounting concerns regarding the dangers of the drug pushed lawmakers and law enforcement officials into action.

In 2004, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) recorded almost 24,000 domestic methamphetamine incidents, which included seizures of labs, dumpsites and chemical or glass equipment. Something had to be done. In 2005, U.S. lawmakers passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act which, among other things, sought to limit access to over-the-counter cold medicines that contain ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, key precursor ingredients for methamphetamine production.

The United States pushed for similar legislation in other countries, including Mexico, which adopted stricter drug controls starting in mid-2007.

At the same time, Mexican criminal organizations were evolving, developing increasingly sophisticated means of mass-producing methamphetamine and distributing it in vibrant U.S. drug markets. The Mexico-produced methamphetamine was both higher in purity and lower in price, and when the new controls on precursors began, the Mexican groups simply shifted gears, moving to more accessible and harder to control precursors. The U.S.-based producers could not compete.

![]()

The combination of the U.S. crackdown and the flood of Mexico methamphetamine gutted the U.S. production market. In 2019, the DEA recorded just 890 domestic methamphetamine incidents.

Now, Mexican organized crime groups are the “primary producers and suppliers of low cost, high purity methamphetamine” sent to U.S. consumers, leading to “significant supply” of the synthetic drug in the U.S. market, according to the DEA.

The rise of methamphetamine in Mexico

As production ramped up, public health officials in Mexico started to notice the emerging threat methamphetamine posed amid a rise in addiction around 2009 or 2010. A decade later, the civil society-led Youth Integration Centers (CIJ), which work with the state’s health sector to combat drug use among youth, reported that methamphetamine use was rising exponentially, becoming the drug most reported by users seeking treatment in their facilities nationwide.

What’s more, the CIJ report found that through the first half of 2020, a growing number of people in their care — more than ever before — reported using methamphetamine at least once in their life. Methamphetamine just barely outpaced cocaine, and fell behind only alcohol, tobacco and marijuana, which may soon be completely legal in Mexico.

“We need to look at methamphetamine as the current substance that’s creating the most problems for people who use drugs in Mexico. We’ve seen an increase in consumption around the country and are suffering the unintended consequences of both preferences for substances and drug policy changes,” said Jaime Arredondo, a professor at the Drug Policy Program at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE) in Aguascalientes.

Methamphetamine is attractive for many reasons. It’s powerful, offers an intense high and is extremely cheap. A user in Mexico can buy one “rock” on the streets for 50 pesos, or around US $2 per dose. Combined with its easy accessibility and the fact that it can be produced in any climate, it comes as little surprise that methamphetamine has spread across the country as crime groups have boosted production to keep up with U.S. demand.

Indeed, in Baja California state, a key drug trafficking corridor home to the border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali, the CIJ reported that methamphetamine was the drug most cited by users in their care between the second half of 2015 and the end of 2018, exceeding all other drugs, including marijuana.

Last year in Tijuana, authorities seized 3,386 kilograms of methamphetamine, more than any other city and almost three times as much as Ensenada, which saw the second-highest rate of such seizures, according to government data compiled by the non-profit Mexico United Against Crime (MUCD).

However, local drug users likely aren’t getting the high-quality product that consumers are in the United States. North of the border, the potency and purity of seized methamphetamine averages more than 97%. The drug is also increasingly being marketed – often unbeknownst to users – as counterfeit Adderall pills in places like New England. In 2019, the DEA made 115 methamphetamine seizures in pill form in that region. Before that, between 2015 and 2018, there were only 13 such pill seizures.

But while headline-grabbing news reports in Mexico often showcase the famous blue pills, Arredondo, the CIDE professor, says it’s extremely rare to see the regular users he interacts with in Tijuana and Mexicali using methamphetamine in pill form.

“It could be that the best product just gets exported to its final destination in the United States, while users continue to use lower quality drugs here in Mexico,” Arredondo told InSight Crime.

Another side effect: violence

Given the rise of the market in the United States, securing safe transport of the high-quality product across the U.S.-Mexico border has become even more important, evidenced in the battles between drug trafficking groups and corrupt security officials operating along these routes. Baja California – just across the border from the San Ysidro port of entry, the busiest land border crossing in the Western Hemisphere – had the highest homicide rate of all of Mexico’s states in 2020, with nearly 80 per 100,000 citizens, more than double the national average.

Of the 34,515 homicides recorded nationwide in 2020, the border city of Tijuana accounted for more than 4,000, or about 12% of all killings, the most of any town.

That said, rates of violence are not tied solely to the drug trade. Local economic and political interests also influence how power brokers use violence as a resource to establish order and maintain power, or to set new rules and configurations.

Further complicating things is the increasingly atomized nature of Mexico’s criminal landscape. Producing methamphetamine takes no agricultural know-how, unlike cultivating poppy for heroin or coca for cocaine. Anyone with access to precursor chemicals, the right infrastructure and the ability to follow a recipe can do it. This low bar of entry allows smaller startup groups to carve out a place for their own operations, taking advantage of a massive market with rising demand and prices.

As things stand now, the lucrative trade shows no signs of slowing, and use of the drug in Mexico is likely to continue. In 2019, Mexico’s National Statistics and Geography Institute (Inegi) reported that the number of citizens addicted to amphetamines jumped 775% since 2000.

With use growing, the array of players is widening. Last month, a former mayor was arrested for his role in brokering a multimillion-dollar deal on behalf of the so-called Cárteles Unidos to deliver half a tonne of methamphetamine hidden in concrete tiles and house paint to south Florida by truck.

Not long after the arrest, members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) — one of the main producers of synthetic drugs like methamphetamine — reportedly stormed Aguililla, the town in Michoacán state the former official once presided over, in what was the start of just the latest power struggle to be waged.

This is the third and final part of a series (read chapters one and two) in which InSight Crime has explored changing drug consumption patterns in the region and its impact on criminal dynamics. Parker Asmann is a writer with InSight Crime, a foundation dedicated to the study of organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean.