The Mexican army has dismantled one of the largest synthetic drug laboratories yet seen in the country in the municipality of Culiacán, Sinaloa.

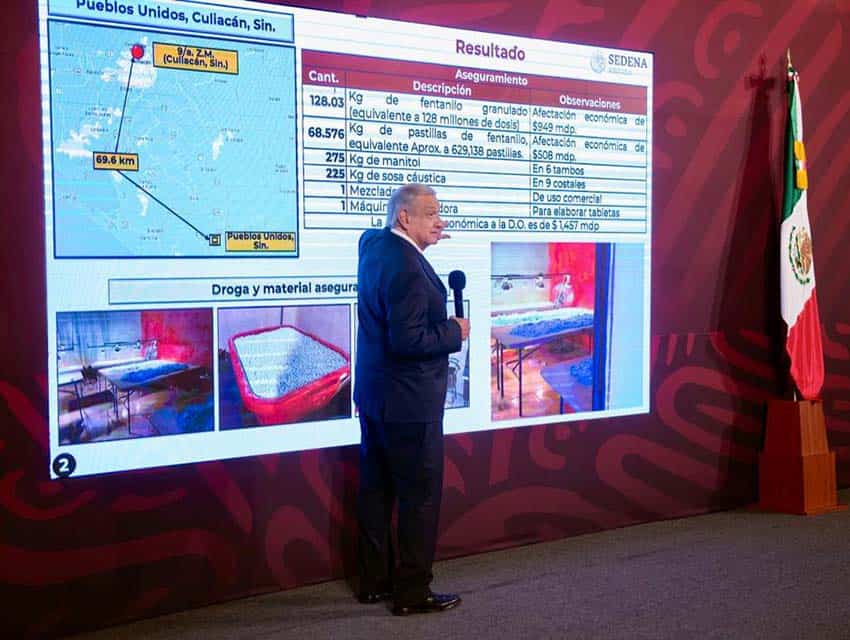

The operation took place on Feb. 14 near the village of Pueblos Unidos. Soldiers found a building used as a fentanyl pill production center, where they seized nearly 630,000 fentanyl pills, 128 kilograms of loose fentanyl and 100 kilograms of methamphetamine.

They also found a laboratory on a nearby plot of land, which contained more than a metric ton of precursor chemicals and 28 organic synthesis reactors used to produce the drugs.

A statement by the Defense Ministry (Sedena) said: “Due to the number of reactors, the laboratory has the greatest synthetic drug production capacity that has been recorded historically and during the present administration.”

In a security meeting on Wednesday, President López Obrador showed two videos of the facilities and said their destruction would have cost their criminal owners more than 12 billion pesos (US $665 million).

“If necessary, I’m going to be talking about this daily,” he said. “This [drug] is the most harmful, destructive thing there can be, this completely alters any organism.”

AMLO is under growing pressure from the United States to tackle the fentanyl trade. The U.S. counted more than 108,000 opioid deaths during 2021, the last year on record. This was largely due to the rise of the highly potent heroin substitute fentanyl, which is mostly produced in Mexico.

“We believe Mexico needs to do more to stop the damage this is causing,” Anne Milgram, head of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) told the U.S. Senate on Wednesday.

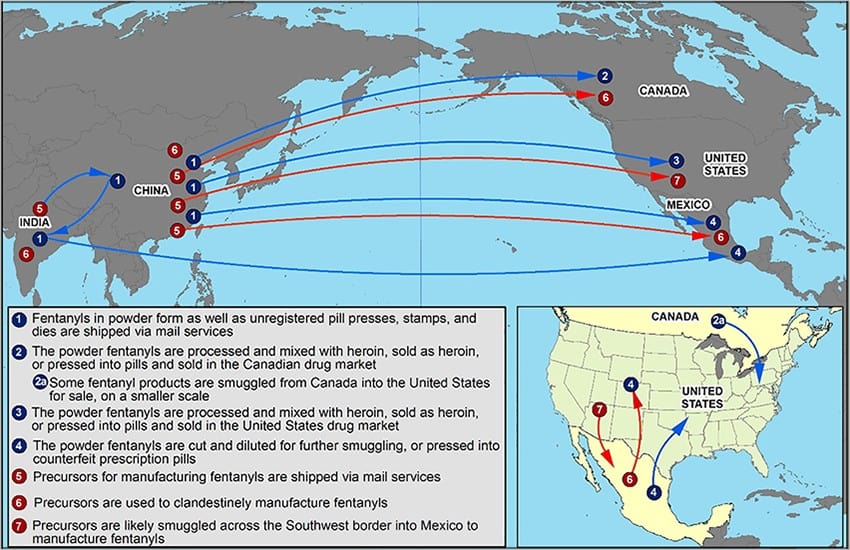

She said Mexico’s two largest criminal organizations – the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation cartel (CJNG) – dominate the fentanyl trade. They import precursor chemicals from China and set up clandestine laboratories to produce the drug, which is often sold in the U.S. in the form of fake prescription pills such as OxyContin or Percocet.

Milgram criticized Mexico for the rapid growth of this trade, arguing that Mexican authorities must do more to share information with their U.S. counterparts, dismantle drug labs and extradite accused drug traffickers to the U.S.

Several Republican and Democratic senators agreed with Milgram, although Todd Robinson, undersecretary of the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, was more restrained.

“I would say that in the conversations we have had, Mexico is willing to do more,” he said.

AMLO was elected on a promise of a “hugs, not bullets,” policy toward crime and the problem of Mexico’s cartels, meaning that he would prioritize social investment in poor areas over drug war policies. However, rising violence and the opioid crisis have pushed him toward a more hardline stance.

During the North American Leaders Summit in January, Defense Minister Luis Cresencio Sandoval told the leaders of the U.S. and Canada that fentanyl seizures had increased by more than 1000% during AMLO’s administration, and meth seizures by 93%.

With reports from La Jornada Maya, Diario de México and El País