President López Obrador offered an apology on Monday for a 1911 massacre in which more than 300 Chinese people were murdered by revolutionary troops and local residents in Torreón, Coahuila.

Speaking at a ceremony in the northern city, López Obrador said the objective of apologizing was to ensure “that this never, ever happens again.”

Accompanied by Chinese Ambassador Zhu Qingqiao, the president noted that the Torreón residents were brutally murdered during a period of anti-Chinese sentiment in Mexico. Their bodies were mutilated or hung from telegraph poles in some cases, he said.

Discrimination against Chinese people was based on “the most vile and offensive” stereotypes. “These stupid ideas were transferred to Mexico, where extermination was added to exclusion and mistreatment.”

Coahuila Governor Miguel Ángel Riquelme said racist ideas were “twisted into genocidal killings” during what he described as a “convulsive” time of history.

The president’s apology came two weeks after he apologized to the Maya people of Mexico for what he described as five centuries of abuse committed by foreign and Mexican authorities and longstanding discrimination that continues to the present day.

As part of a year-long series of events to commemorate and apologize for past injustices, López Obrador said he also intends to make an apology to the indigenous Yaqui people of Sonora, who have long been victims of government abuse and discrimination.

His apology for the Torreón massacre, in which 303 Chinese men, women and children were killed, came just over 110 years after it occurred.

On May 13, 1911, revolutionary troops overran Torreón — then a booming railway town with lines running north to the United States — after outnumbered federal forces abandoned their positions following clashes on the town’s outskirts.

The revolutionary soldiers proceeded to indiscriminately murder Torreón’s Chinese residents during an occupation that sealed the fate of then president Porfirio Díaz: the long-serving dictator resigned shortly after the takeover and went into exile.

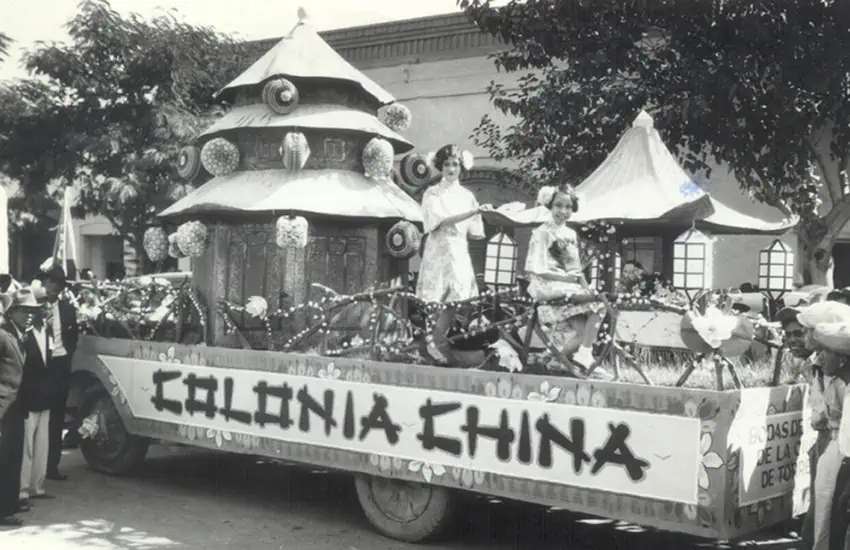

Many Chinese people came to Mexico in the 1800s to laborers, many working on projects to expand the country’s railroads. In Torreón, Chinese immigrants set up businesses and farms, opened a bank and built a tram line to the nearby city of Gómez Palacio, Durango.

As the troops entered the city, the revolutionary forces were joined by thousands of local residents who were opposed to the presence of Chinese people, believing that they were taking jobs from Mexicans and keeping wages low. Some Mexicans were also jealous of the Chinese community’s economic success, according to the Associated Press.

An article by the newspaper The Guardian told of a herb seller who was said to have clutched a Mexican flag and yelled, “Let’s kill the Chinese!” shortly after the revolutionary troops arrived in Torreón. A commander of the revolutionary forces, Benjamín Argumedo, is believed to have given the order to kill residents of Chinese ethnicity.

“Over the next 10 hours, the mob sacked Chinese-owned businesses, looted the Chinese bank and dragged their Chinese neighbors by their distinctive braids, trampling them to death with horses,” The Guardian said.

The bodies of the dead were taken out of the city in horse-drawn carts and buried in mass graves. Like most racial killings, the Associated Press reported, the massacre was fueled by suspicion, hatred, fear, envy and lies.

A significant portion of Torreón’s Chinese community was killed, although some were able to hide or were protected by sympathetic Mexicans. A local lumberyard owner provided shelter to some residents, The Guardian said.

The revolutionary government of Francisco Madero, who became president in late 1911, agreed to pay compensation for the massacre — one of the most vicious manifestations of the wave of anti-Chinese racism that swept across North America in the 19th and early 20th century — but Madero was ousted and killed in 1913, and the reparations were never paid.

Nobody was held accountable for the massacre, and today there are no monuments commemorating the tragedy.

“A commemorative plaque was swiftly stolen. A statue erected in a public park in 2007 was vandalized and later removed but will be restored to a public plaza,” The Guardian reported.

Historian Monica Cinco Basurto told the Associated Press that there were many other acts of violence toward Chinese people in Mexico. She said that the looting of Chinese-owned businesses continued into the 1930s in northern Mexico and many Chinese people were expelled from the country even though some had Mexican citizenship, Mexican wives and Mexican-born children.

More than a century after the massacre, Torreón today has a Chinese population of about 1,000 people, and there are also Chinese communities in many other parts of Mexico. Many survivors of the 1911 violence fled Torreón, but some later returned to the city.

The killings and mistreatment of Chinese people in Mexico caused anger in China, but the relations between Beijing and Mexico City are cordial today. The two countries have in fact grown closer as the result of the assistance China has provided Mexico during the coronavirus pandemic.

At yesterday’s event, Ambassador Zhu said the shipments of more than 10 million Covid-19 vaccines and medical equipment China has sent to Mexico “have left a strong imprint on the history of relations between our two countries.”

For his part, López Obrador said that Mexico “will never forget the brotherhood of the Chinese during the bitter and anguishing months of the pandemic.”

Source: AP (en), The Guardian (en)