Standing before an onshore oil well in his home state of Tabasco last March, President López Obrador made familiar promises to halt the privatization of energy in Mexico and save the country’s oil industry for the people.

“We’re rescuing Pemex and we’re rescuing the nation,” he said, nodding to the national oil and gas company.

His state-led vision for the country’s energy policy and Pemex celebrates the past. But it is threatened by a more 21st century concern: the lack of a concrete environmental, social and governance (ESG) strategy as its peers pivot towards a greener future.

This could become a problem for Pemex, which is fully state-owned but has debt pile of more than US $100 billion, as debt investors are increasingly screening out companies that perform badly on ESG metrics, bondholders have said.

Greenhouse gas emissions at the oil behemoth, which was created in 1938 after Mexico expropriated U.S. and U.K. oil assets, rose in 2019 and 2020. In 2020, greenhouse gas emissions in extraction and production were 31.6 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per thousand barrels. That is more than one-third above that year’s target of 23.34 tonnes per thousand barrels.

Most oil and gas majors are not achieving overall emission reductions, but many are improving on carbon intensity and have longer-dated targets than Pemex, said Jonathon Smith, manager for oil and gas research at Sustainalytics, a unit of Morningstar.

Sustainalytics placed Pemex 253rd out of 261 in a ranking of how well oil and gas producers are managing ESG risks. The ratings and data provider judged Pemex’s exposure to risks associated with emissions and worker safety as “severe.”

Recent results from ExxonMobil, Chevron and others show that despite promises of a greener future decades down the line, betting on oil can still be highly profitable for investors when prices rise.

Part of the attraction of Pemex is the higher return on offer in comparison with the Mexican government or its peers. Pemex’s latest 10-year bond, which it sold in December, offers a yield of more than 7%, while a 12-year dollar-denominated sovereign bond issued in January pays a yield of around 4%.

While investors such as Fidelity, Capital Group and BlackRock all hold north of $1 billion in Pemex debt, a clearer ESG plan is regarded as crucial to luring in more investors that might push up prices and help reduce the company’s borrowing costs.

“The incremental spread you get on their bonds is multiples higher than any other quasi-government oil company . . . the ESG overhang is adding to the pain,” said Akbar Causer, emerging markets portfolio manager at Eaton Vance. “As more managers have ESG restrictions, more managers aren’t able to hold Pemex’s debt in their portfolios.”

Although Latin America is home to some of the energy industry’s last fossil fuel holdouts, analysts agree that Pemex lags behind other regional national oil companies such as Brazil’s Petrobras and Colombia’s Ecopetrol on ESG matters. Despite some scepticism, it is also starkly at odds with plans by large groups such as Shell, BP and Total that have all set net zero emissions targets and are investing in renewables as they manage the energy transition.

“If they [Pemex] want to remain a viable company for the medium to long term they have to implement ESG,” said Aaron Gifford, emerging markets sovereign analyst at T Rowe Price, one of the largest holders of Pemex bonds.

Although Pemex’s emissions targets are not well publicized, Gifford and others have seen some signs of improvement in the last couple of years. The group has started to mention ESG briefly in quarterly reports such as including an indicator on natural gas flaring, is engaging privately with investors and said in its most recent quarterly earnings that it had identified 209 environmental risks, although it provided little detail.

“It is clear that they’re coming around to the fact that this is an urgent matter . . . for now we are all just kind of waiting for actual measures and longer-dated targets,” Gifford said.

Alex Collins, an emerging markets corporate analyst at Pemex bondholder BlueBay Asset Management, said he had been engaging with the group for 18 months on ESG. He said he thought they did want to do more, but had a long list of other priorities. “They do care, they’re just doing a 4D Sudoku,” he said, referring to the puzzle game.

Neither fund manager has plans to divest, but BlueBay warned that their clients increasingly ask them to screen out poor performance on ESG. Pemex’s primary ESG issues are around emissions and the environment as well as its record on accidents and worker safety, analysts said.

Pemex did not respond to a request for comment.

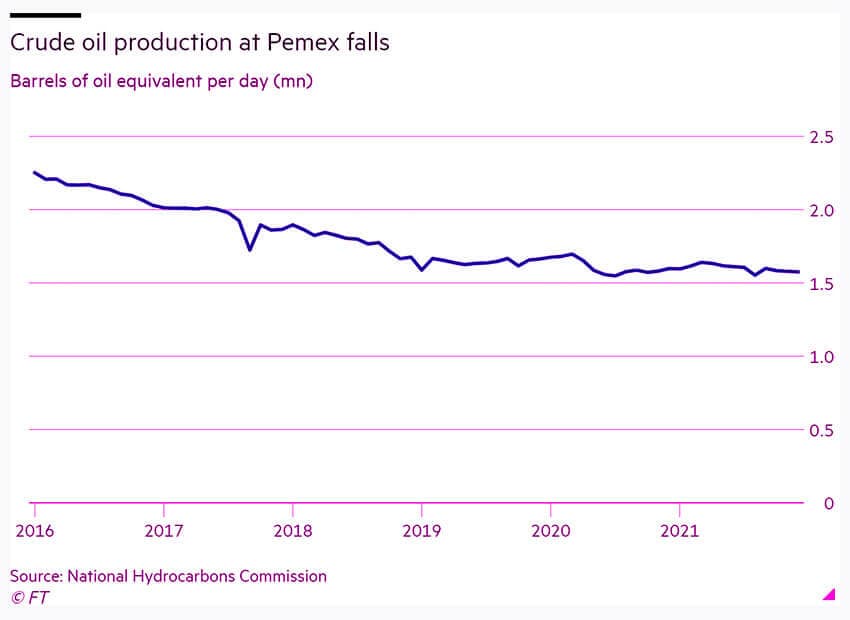

Now, the president’s nationalist vision is making it even harder to allocate the focus and capital for a climate-focused transition. After he was elected in 2018, López Obrador inherited Pemex with a huge debt pile built up over years of declining production and bad investments. It also had massive quarterly losses and was in the throes of a major reform instigated by a previous administration that opened it up to private competition for the first time in its history.

Many analysts believe the best business strategy would be for the company to focus on its more profitable exploration and production arm, while making a credible plan to address ESG.

But López Obrador has instead prioritized the downstream business in his quest to make the country energy “self-sufficient.” He wants to stop exporting crude and importing petroleum products and instead extract, refine and use them locally.

The government has been criticized for its doubling down on fossil fuels, including trying to pass a constitutional reform to guarantee more than half the electricity market to state company CFE. Critics have said the reform would make electricity more expensive and halt private investment in renewables.

“It’s a strange bet to say the least,” said Carlos Elizondo Mayer-Serra, a professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey university and a former Pemex board member. “It’s a president and a team that don’t really understand the implications of developed countries’ fight against climate change.”

At the end of last year, Pemex said it would effectively stop crude exports by 2023. “The doubling down of Pemex’s strategic shift towards lossmaking downstream activities underlines how ideological considerations continue to eclipse commercial logic,” Nicholas Watson, managing director at Teneo, said after the announcement. “The plan is unrealistic and is unlikely to develop in the official timeframe.”

Pemex chief executive Octavio Romero Oropeza offers little challenge to the administration. An agronomist with no prior oil sector experience, he is a longtime collaborator of López Obrador.

The president has followed through on pledges to financially support the company, something bond investors have long paid keen attention to. The government cut a key tax rate Pemex pays to 40% in 2022, down from more than 65% in 2019. It also recently agreed to buy back some bonds and swap others to the tune of more than $3 billion.

“The financing side is where they focused the most this year . . . I would say there they’ve made very good progress,” said Simon Waever, a strategist at Morgan Stanley. “On fundamentals, it’s a bit more challenging . . . clearly the biggest challenge is getting production up in line with their plans but for now capex just isn’t enough.”

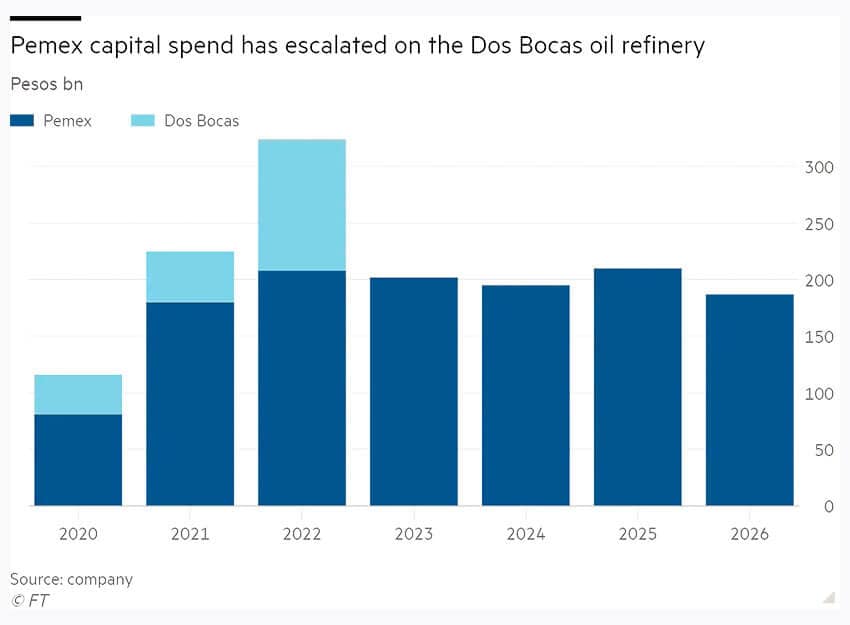

Around one-third of the company’s capex this year will go into the new refinery at Dos Bocas in Tabasco, according to an investor presentation from June. Last year, it bought out partner Shell’s stake in their Texas Deer Park refinery.

The former is a flagship project in the president’s native state that is officially due to open in the summer, but analysts doubt it will be ready to produce before 2023. An activist has filed a legal challenge against the project, claiming it was built on environmentally protected land.

In tandem with the financial support, the finance ministry promised a reformulated business plan for the company, but it faces a tall order to placate investors and analysts who want to see progress both on ESG and the fundamental strategy.

“It’s going to be interesting to see what exactly this whole . . . plan really entails,” said John Padilla, a partner at Latin America-based energy consultancy IPD. “If it doesn’t address ESG, if it doesn’t address the refining dynamic, if it doesn’t address the fundamental issues that you’ve got with production then it’s just more window dressing.”

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.