Drug cartels are collectively one of the largest employers in Mexico, employing more people than the ubiquitous Oxxo convenience store chain and the state oil company Pemex, according to a research article published in the journal Science on Thursday.

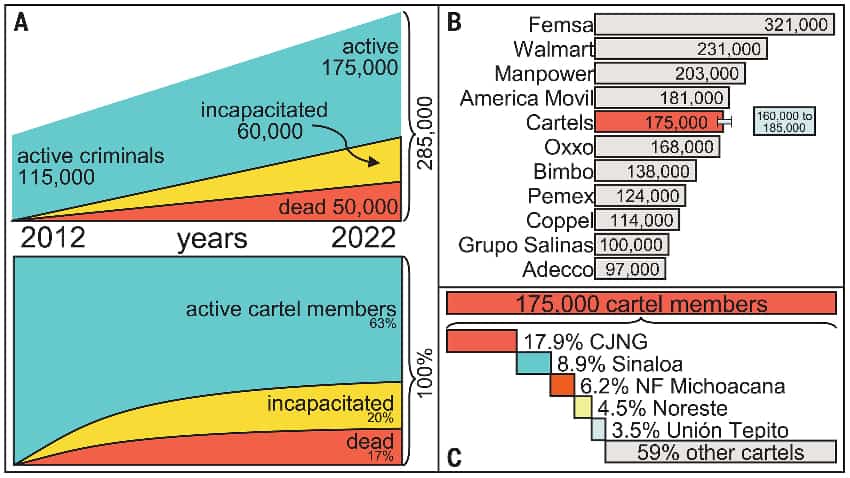

Using a mathematical model that takes things such as cartel recruitment, homicides and incapacitation of members due to imprisonment into account, the authors of the article calculated that cartels employed between 160,000 and 185,000 people in Mexico in 2022.

“To construct our model, we gauge data on 150 cartels active in Mexico in 2020, including information on their alliances and rivalries and data corresponding to homicides, missing persons, and incarcerations,” the authors said.

With an estimated 175,000 people on their payroll, organized crime groups including the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) and the Sinaloa Cartel are Mexico’s fifth largest employer, the researchers concluded.

Only Femsa, a beverage and retail company and Coca-Cola bottler, Walmart, staffing firm Manpower and telecommunications corporation América Móvil have more employees in Mexico, according to the study.

Cartels’ employees include producers of drugs such as methamphetamine and fentanyl, smugglers, sicarios or hitmen, hawks or lookouts, recruiters, accountants and money launderers. Police or politicians who receive payments from cartels could also be considered employees.

Published under the headline “Reducing cartel recruitment is the only way to lower violence in Mexico,” the article – after citing data and mathematical calculations – said that “despite efforts from the state to hinder their power, cartels have increased their size by 60,000 members in a decade” between 2012 and 2022.

“Incarcerating nearly 6000 cartel members each year has not prevented them from growing into larger organizations,” the three authors said.

Why? Cartel recruitment, as the research article explains.

“Between January and December of 2021, cartels recruited 19,300 individuals, losing 6500 members as a result of conflict with other cartels and 5700 members as a result of incapacitation, which resulted in a net gain of roughly 7000 members during that year…A similar estimate is observed for each year between 2012 and 2022,” the authors said.

“Unless all cartels combined recruit between 350 and 370 people per week, they would have collapsed as a result of conflict, incapacitation, and saturation combined,” they added.

The article explains that “saturation” is indicative of “internal instability and dropouts, which lead to organizational fragmentation.”

The authors – Rafael Prieto Curiel, Gian Maria Campedelli and the recently deceased security analyst Alejandro Hope – calculated that the “10 largest cartels in Mexico have more than 50% of the active affiliates in the country.”

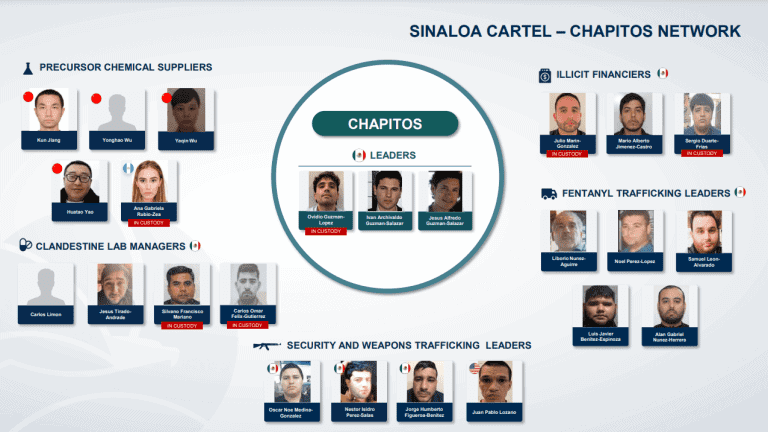

Of the estimated 175,000 cartel affiliates (or employees), 17.9% work for the CJNG and 8.9% are on the Sinaloa Cartel payroll, the researchers calculated. The Nueva Familia Michoacana, the Northeast Cartel and the Unión Tepito were identified as the next biggest criminal employers.

While over 50% of “active affiliates” work for the 10 biggest cartels, “the conflict between them only produces 15% of the fatalities [in Mexico], ” the article said before noting that the country’s most powerful criminal organizations often target small local ones in order to incorporate them into their own structures.

“… We estimate that more than half of the country’s casualties result from the fight between the smallest 140 and the largest 10 cartels,” Prieto, Campedelli and Hope said.

The authors outlined a concerning possible scenario for coming years based on the growth of cartels and the increase in homicide numbers seen over the past decade.

“On the basis of the size of cartels in 2022 and the trends observed in the past decade, we predict that the weekly number of casualties related to organized crime will keep increasing in the coming years,” they said.

“We estimate that if current trends continue, cartels will keep increasing their power, and we could observe 40% more casualties and 26% more cartel members by 2027.”

The key to avoiding that scenario, the authors argued, is reducing cartel recruitment rather than increasing arrests.

“Decreasing the cartel’s ability to recruit by half will reduce the weekly casualties by 2027 by 25% and cartel size by 11%,” they said.

The researchers also calculated that “even in the hypothetical scenario where recruitment drops to zero, it would take three years to return to the – already high – levels of violence observed in 2012.”

“This further calls for rapid and timely large-scale initiatives to reduce recruitment in the country,” they said.

Tackling recruitment, the authors said, “will have a triple effect in the future.”

“First, it will lower the number of cartel members, reducing the violence that it can create by having fewer killers. Second, it will lower the number of targets, so fewer people are vulnerable to suffering more violence. And third, it will reduce the cartel’s capacity for future recruitment,” they said.

Prieto, Campedelli and Hope said that “offering policy recommendations is beyond the scope of this work,” but argued that “reducing recruitment requires structural efforts at the state and local levels.”

“This especially applies to areas with high cartel support, where offering educational and professional opportunities that outweigh the short-term benefits offered by cartels represents a critical goal for the future of the country,” they wrote.

President López Obrador agrees. His government has implemented a so-called “hugs, not bullets” security strategy that seeks to address the root causes of crime by offering work and education opportunities to Mexicans, especially the nation’s youth.

The “hugs” part of the strategy includes the provision of educational scholarships and employment programs such as the Sowing Life reforestation scheme and the Youths Building the Future apprenticeship initiative.

Despite the government’s efforts to tackle crime and violence in those ways, homicide numbers have hit record high levels during López Obrador’s administration, although there was a decline of almost 10% in 2022 compared to the previous year. The president has repeatedly said that his security strategy will take time to “bear fruit.”

The publication of the cartel-focused research article in Science comes eight weeks after United States Drug Enforcement Administration chief Anne Milgram asserted that the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG have more than 40,000 operatives in over 100 countries around the world.

She says that those two cartels pose “the greatest criminal threat the United States has ever faced” given the large quantities of narcotics, including the powerful synthetic opiod fentanyl, they ship to the U.S.

Prieto, Campedelli and Hope said that their work, to the best of their knowledge, “represents the first scholarly attempt to mathematically quantify the size of the cartel population in Mexico.”

They acknowledged “some limitations,” saying that while “the lack of data on the size of cartels represents the inherent motivation of this work, it also represents a structural limitation because our estimates cannot be meaningfully validated with real-world information.”

Victoria Dittmar, a project manager at Insight Crime, a think tank and media organization that researches crime in the Americas, noted that she hadn’t seen any other estimates of cartel member numbers in Mexico.

Quoted in a report by The Guardian, Dittmar expressed some reservations about the study, commenting that “it can be very difficult to say who is a member of a criminal organization, and who isn’t.”

“What about a politician that receives money? Or someone who cooperates with the group just once?” she asked.

Ioan Grillo, a British journalist with vast experience reporting on cartels in Mexico and further afield, said in an article on his Substack site that he was “skeptical of seeing formulas and precise numbers” on cartel activities.

However, he also wrote that he “instinctively” agreed with its conclusions.

“Cartels do employ a hell of a lot of people, perhaps even more than the study finds, and it’s important to point out this colossal problem,” Grillo wrote.

“Preventing youths from joining them has to be key to finding a way out of this mess.”

Mexico News Daily