It’s a 15-hour drive from the Pacific coast port city of Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán, to the northern border city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas.

The former city – along with other Pacific coast ports such as Manzanillo, Colima, and Acapulco, Guerrero – serves as a gateway for the importation of drugs such as methamphetamine and the synthetic opioid fentanyl from Asian countries, especially China.

Reynosa, like other northern border cities, lies on the brink of the world’s largest drug market, the United States.

That makes the route between the two of major importance to criminal organizations such as the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), easily the most dominant such organization in the Pacific coast port cities of Lázaro Cárdenas, Manzanillo and Acapulco.

It operates in almost every state in Mexico, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, but while it completely controls criminal activities in some states, it doesn’t have the same dominance in the north of the country.

The Sinaloa Cartel, once led by imprisoned notorious kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, dominates in much of the border region between Tijuana, Baja California, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, while the CJNG wields substantial, although not uncontested, influence in Tamaulipas, the border state where Reynosa is located.

Therefore, moving drugs from the Pacific coast to the United States via Reynosa has two advantages: it saves the CJNG time because it is the shortest route to the northern border, and smuggling efforts into the U.S. are more likely to succeed because of its established – and significant – presence in Tamaulipas.

But there’s a catch. Getting from Lázaro Cardenas, or Manzanillo, to Reynosa in 15 hours entails going through Guanajuato, a state that the CJNG would like to control, criminally speaking, but doesn’t – at least for now.

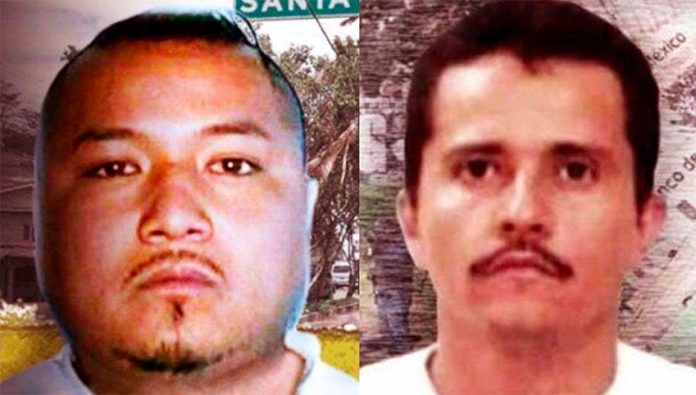

In addition to the possibility that cartel operatives could run afoul of government security forces, hindering a smooth run from the glistening waters of the Pacific to Texas’ doorstep is the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel, a Guanajuato-based fuel theft, drug trafficking and extortion gang headed by one of Mexico’s most wanted men, José Antonio “El Marro” Yépez.

In that context, according to a report published by the newspaper Milenio, CJNG leader Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes – a man with a US $10-million price on his head in the United States – sent one of his nephews to Guanajuato in January 2017 to negotiate with the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel with the aim of securing a safe passage through the state.

Yépez and his cartel henchmen, Milenio reported, were offered the opportunity to form a loose alliance with the CJNG. In exchange for accepting the offer, El Mencho and his men would stay out of the Santa Rosa gang’s lucrative fuel theft activities in Guanajuato, home to one of Pemex’s six refineries and hence several petroleum pipelines ripe for illegal tapping.

However, the conversation with Oseguera’s nephew didn’t go well, Milenio said. El Marro wasn’t interested in striking a deal with – or serving – anyone and was apparently sufficiently offended to have his sicarios, or hitmen, murder the CJNG envoy at an Irapuato coffee shop where the meeting took place.

Rejecting Oseguera’s offer, and having his nephew killed, made El Marro enemy No. 1 of El Mencho, an animosity that endures to this day and which has made Guanajuato the most violent state in the country.

Instead of leaving the Bajío region state as the criminal domain of the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel, and using it solely as a piece in the drug smuggling puzzle between the Pacific and the Mexico-United States border, the CJNG moved into Guanajuato and launched a full-blown turf war against El Marro and his co-conspirators.

And thus two underworld kings, El Mencho, rey de metanfetamina (meth king) and El Marro, rey de huachicol (fuel theft king), have turned once-peaceful Guanajuato into a blood-soaked battlefield in a near-incessant war that both men are loathe to lose.

There were more than 3,500 homicide victims in Guanajuato last year – with a significant proportion of the murders attributed to the turf war – and the state has hung on to the unwanted title of Mexico’s most violent in the first five months of 2020.

The third participant in the dispute is, of course, the Mexican state but neither federal security authorities, nor their state counterparts, have succeeded in quelling the violence in Guanajuato – the killing just goes on and on.

Authorities have thus far also failed in their attempts to apprehend El Mencho and El Marro, although members of both men’s families have been detained.

However, keeping the men’s family members in prison has proven to be a challenge: Oseguera’s wife, an alleged CJNG financial operator, was released on bail in September 2018, while Yépez’s wife, mother, father, sister, cousin and niece, among other relatives, have all been arrested only to be later set free.

While El Mencho and El Marro remain at large, the demand for drugs in the United States stays high and authorities’ apparent incapacity to combat the two cartels continues, the violence in Guanajuato appears set to persist.

A truce between the two criminal “kings” could perhaps put an end to the bloodshed but given their history, that scenario seems about as likely as President López Obrador’s non-confrontational “hugs, not bullets” security strategy ending all violence in the country tomorrow.

Mexico News Daily