Ranchers from Mexico’s eastern state of Veracruz know a way to buy cheap cattle: Drive to a remote part of the Chiapas-Guatemala border and purchase cows being brought illegally across. But behind the smugglers and the brokers, those who allow this thriving business to exist hide in the shadows.

Benemérito de las Américas may be one of the most isolated towns in Mexico. Sitting on a remote part of the Mexico-Guatemala border along the Usumacinta River, hundreds of kilometers away from the nearest city, the town has no customs presence and no formal border crossing. It has one gas station, one supermarket, one hotel and a few restaurants.

Yet it is a thriving hub for a growing transnational economy: cattle smuggling.

The river near Benemérito is crowded with a large number of boats carrying cattle and other types of contraband from Guatemala to collection points dotted along the Mexican side, usually at ranches. Dozens of tractor-trailers, loaded with cattle, wait to fuel up at the gas station or are parked outside the offices of the local cattle ranchers’ union.

One rancher, Eduardo, heard of the brisk cattle business in Benemérito and decided to travel there from his home in the south of Veracruz state. He wanted to see first-hand the level of competition he was up against.

“Buyers prefer to go there [to Benemérito] because it is cheaper. The cattle that come from Central America are not subject to the controls that we are forced to have,” he told InSight Crime.

Eduardo was in an ideal position to profit. As a member of Mexico’s National Confederation of Livestock Organizations he believed he had the contacts needed to get access to ranches in Guatemala where the cattle are collected before being moved to Mexico. The reality was a letdown. According to Eduardo, just before entering the center of Benemérito, a small road leads down to the Usumacinta River. Long, wooden canoes, carrying dozens of cows and calves, arrive there and unload their cargo. Eduardo appraised the cows as “old and rough.”

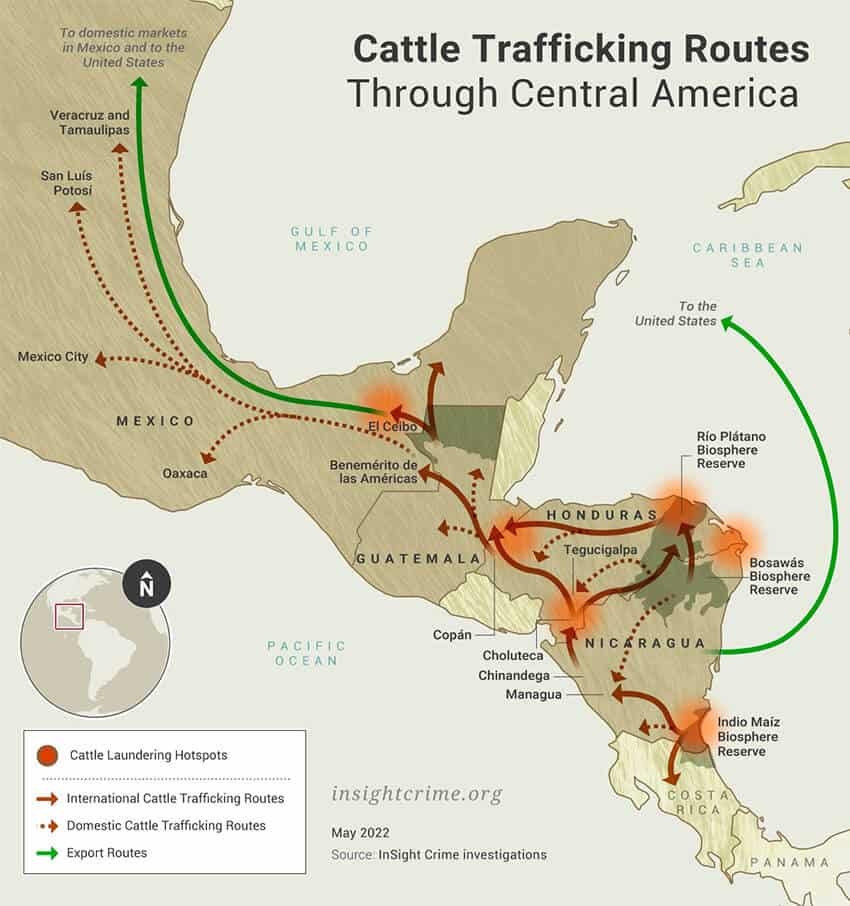

Crossing into Guatemala to inspect the cattle proved impossible. “The cattle come from Nicaragua and are gathered in Guatemala to bring them to Mexico,” he said, having learned this during his trip. “Armed people guard the transfer of cattle. They told us not to go any farther. Criminal groups are taking care of this business,” Eduardo added.

Another source from Veracruz, Gilberto, had been buying cattle in Benemérito for eight years. He was tasked with procuring cattle from Guatemala for a number of farms up the coast of Veracruz in eastern Mexico and delivering them to their buyer.

Gilbert told InSight Crime that ranchers seek to increase their production levels with cattle from Central America, since production in Mexico is low while demand is always increasing. “That area [Benemérito] is very tricky. You deal with bad, bad people. Many heads have fallen in this business. But if you show up and respect the deals, you won’t have a problem,” he told InSight Crime.

In all that time, Gilberto never met those who actually owned the cattle being sold. He only dealt with brokers. “It is very difficult to reach [the people who sell the cattle]. You will never talk to them, you will never know who they are,” said the rancher.

Gilberto never asked any questions. He bought the cattle and left.

The entire cattle trafficking industry is shrouded in secrecy. During field work in Benemérito, InSight Crime learned that the identities of those who own the ranches near the town are also hidden. “The town has no formal customs or tax office. But it has a different sort of ‘customs’ presence,” said one source in the town, who is connected to cattle trafficking but requested anonymity.

Several large properties along the river through which the cattle pass in both Mexico and Guatemala are owned by one person, referred to as La Aduana (Customs). “They call him Customs because his lands are half in Guatemala and half in Chiapas,” explained the source, who added that ranchers frequently quip that “they brought animals through Customs.”

The well-worn path

It is no coincidence that the ranchers InSight Crime spoke to were from Veracruz. This state, which takes up much of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, is a cattle powerhouse. One of the main beef-producing areas in the country, it is also a major corridor for the transport of cargo from southern Mexico to the United States.

And in August 2021, cattle ranchers and smugglers alike in southern Veracruz took notice when they heard about a specific arrest. On August 15, authorities in Mexico City announced the capture of a man identified only as Jovanni “N,” alias “El Vani.” His arrest document listed him as a member of the Familia Michoacana, an important if dwindling criminal group from the western state of Michoacán. He faced a raft of charges, including kidnapping, extortion, drug trafficking, criminal association and possession of firearms exclusively for use by the army. When police went to arrest him, he allegedly tried to bribe them with $2 million Mexican pesos (around US $100,000) to let him go.

There was no mention anywhere of El Vani being involved in cattle trafficking. Yet, according to multiple interviews carried out by InSight Crime, El Vani was the lynchpin of the entire cattle trafficking operation between Benemérito and Veracruz.

“If you want to know about cattle from Central America being trafficked to Mexico, he is the key,” one source from Coatzacoalcos, in southern Veracruz, told InSight Crime shortly after El Vani was arrested.

One rancher, respected as a leader in his community, only agreed to speak about El Vani if no details were given about where the interview took place. “He was not famous among the population, only among certain circles of ranchers. He dealt with the most powerful ranchers, those at a very high level. He didn’t give the little ones any attention,” he told InSight Crime.

Controlling the local cattle trafficking trade had made El Vani a wealthy and influential man. Hailing from the town of Carranza, right on the Veracruz-Chiapas border, his house is the most famous building around, so ostentatious it is known locally as “Disneyland.” Residents of Carranza also said that the nickname El Vani may have been invented by authorities because locally he is known as “El Gallo” (The Rooster), a nickname given to brave or aggressive people.

In addition to the Disneyland mansion, Carranza has many cattle ranches, where thousands of animals are fattened up and sold each year.

One rancher, who is also a member of one of the 19 vigilante groups in the region, recalled an instance where one of their colleagues was kidnapped by a local criminal group and El Vani, not the authorities, helped to free him. Like all those who dared to speak about El Vani, he requested complete anonymity.

When El Vani’s brother was similarly kidnapped, the community rallied to help. “We brought a group to help him, and they quickly released the brother. El Vani thanked us personally,” said the rancher.

Another source in Veracruz, who described El Vani as a good friend, said “you could deal with him when he was good and healthy [meaning sober]. The problem was that when he got drunk, the devil got in him. He would start shooting and doing ugly things.”

But beyond these glimpses and personal stories, it proved very difficult to gain a clear picture of exactly how El Vani’s business worked. The scale of this criminal economy though was evident.

Mexico’s National Agricultural Health and Safety Service (SENASICA) estimates that around 800,000 head of cattle annually are smuggled into the country from Guatemala, though no data has yet been published. These cattle are sent to states across the country, where they both complement national meat production for consumption in Mexico and exports to the United States.

Ranchers interviewed in Veracruz and Chiapas told InSight Crime that each animal introduced from Guatemala is sold for approximately $400. This means that cattle being smuggled in could potentially be worth around $320 million a year.

![]()

El Vani’s arrest temporarily slowed this business down. A leading rancher from Veracruz told InSight Crime that after he was detained, those rounding up the cattle in Guatemala and bringing them into Mexico were forced to adjust. “Today, [the business] has slowed down, not so many cages [vehicles with cattle] are entering. It’s complicated,” he said.

“Does the slowdown have to do with El Vani’s arrest?”

“Yes, yes. But they are regrouping. While they are reorganizing and reaching new deals, it’s slowed down. But [this pause] won’t last long because there are a lot of interests here.”

Those other interests soon became clear. The entry of cattle from Central America to Mexico also serves as a shield to bring in cocaine. “The entry of livestock is a very, very sensitive and dangerous issue because it is in the hands of organizations who do not generally deal with livestock. It is a façade, behind which other things can be brought in,” he explained.

Ranchers and local officials in southeastern Mexico confirmed to InSight Crime that cocaine is often smuggled in alongside the cattle. The way in which the smuggled cattle are then “laundered” in Mexico and enter the legitimate supply chain also offers drug trafficking operations a chance to launder money. “It is a double business [livestock and drug trafficking]. It’s very, very big,” said the rancher, who is a member of the vigilante groups.

The arrest

And suddenly, the circumstances of El Vani’s arrest may begin to make more sense. Statements from authorities made zero mention of any involvement in cattle smuggling, claiming that he was engaged in “drug trafficking inside and outside the country.”

Some more light was shed on El Vani’s possible connections to La Familia Michoacana. One rancher from Carranza told InSight Crime that El Vani had many friends from Michoacán and that many ranchers in Veracruz hailed from the western state.

In fact, InSight Crime learned from interviews in the region that one of the most prominent ranchers in southern Veracruz, who is close to El Vani, is the brother of one of the foremost gang bosses and drug traffickers in Michoacán. This rancher did not respond to several interview requests and there is no evidence to date that he is involved in any illegal activity.

Yet authorities have remained quiet about any connections between El Vani and cattle. At the time of his arrest, Veracruz state Governor Cuitláhuac García publicly stated that local prosecutors were investigating the case, but never once referred to livestock.

InSight Crime tried to dig deeper. Requests for information from prosecutors in Veracruz, Chiapas and Tabasco, all key states for cattle smuggling, came up empty. The local Attorney General’s Office in Mexico City, where El Vani was arrested, said it was not looking into his case and that the federal Attorney General’s Office was handling the investigation. They did not respond either.

Finally, InSight Crime turned to Mexico’s National Transparency Platform to request any documentary evidence about El Vani. The request was denied, and the information deemed confidential.

This is the second article in a three-part investigative series by InSight Crime, a foundation dedicated to the study of organized crime. The series looks at how cattle produced in Central America are smuggled into Mexico and laundered in a variety of ways to enter the legal food supply chain before beef products are consumed in both Mexico and the United States. Read the full investigation here.