The Mexican drug war is an issue as complex as it is violent. Over the past two decades, almost 200,000 Mexicans have been killed, and reporting on it is as dangerous as any conflict – more than 100 journalists have been killed, or disappeared, in the same period.

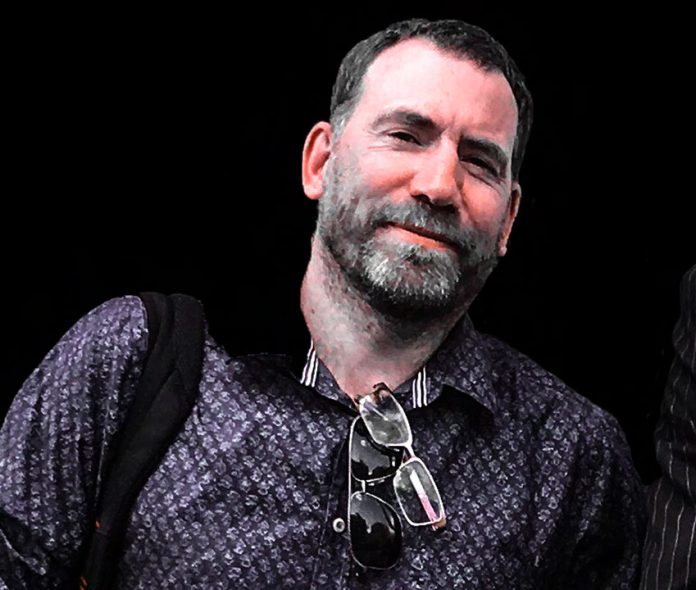

British-born journalist Ioan Gillo has covered the conflict for Time magazine and The New York Times, and in two critically acclaimed books, El Narco (2011) and Gangster Warlords (2016). I met with him to try to understand the war and began by asking him to outline its main players.

IG: Right now you’ve got a lot of fragmentation. You’ve got the Sinaloa, the oldest and most infamous cartel, run by Chapo Guzmán and his sons (“Los Chapitos”), and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, based out of Guadalajara. Then there’s Los Zetas, the first paramilitary cartel, who have now split into factions; and the Gulf Cartel in Tamaulipas and Veracruz; the Juárez Cartel; and the Tijuana Cartel.

Then we come to the smaller cartels, the cartelitos: the Guerreros Unidos, Los Rojos, Los Caballeros Templarios and La Familia Michoaana. There are dozens of these.

ME: How wide are their operations?

IG: Oh, worldwide! The largest cartels have envoys everywhere. There’s a big presence in the U.S., the Caribbean and South America, but they are also active in Britain, mainland Europe, China, even Russia.

ME: What launched the cartels as a global force?

IG: There’s no single watershed moment, but the breakdown of the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party] was a big factor as it broke communication between municipal police forces. What was a stable system of top-down, endemic corruption suddenly became an unstable system of bottom-up, endemic corruption.

Another factor was the re-routing of the cocaine as it came into the U.S. After [former U.S. president] Reagan clamped down on the Caribbean route into Miami, cocaine started to steam through central America into Mexico, which became the final strait. After that the cartels began purchasing the cocaine directly from the Colombians at the border and selling it on. With more money came more violence for control of that money.

ME: Is it just about cocaine and other drugs, or are there other significant revenues?

IG: Concerning narcotics, there are five main products. The first is marijuana, a big cash crop. It’s inexpensive to manufacture and fetches a decent profit margin. However, legalization in the U.S. is damaging its reach. The second is cocaine – traditionally most profitable. A kilo of pure cocaine can be bought by cartels at the border for as little as US $2,000 and sold for a huge mark-up.

Then there’s heroin, which is now largely cultivated in Mexico. If you buy a wrap of heroin in Baltimore today, chances are it’s made in Mexico. Fourth, there’s methamphetamine, which ripped through Mexico after the 2005 Combat Methamphetamine Act in the U.S. And recently we’ve been seeing fentanyl being made in Mexico. This is a seriously dangerous opiod, responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths.

However, on top of the drugs, there’s anything and everything else. Stealing crude oil is big business for oil racketeers known as huachicoleros and other revenue comes from capturing agricultural plantations – avocados and limes, illegal iron mining, illegal logging. And there are the repugnant practices of people smuggling and people trafficking.

ME: Do you know how much overall revenue comes from all of this? And where it goes?

IG: It’s impossible to know. However, the Rand Center, commissioned by the White House, estimated the U.S. spends $100 billion per year on illegal drugs. Obviously much of that will not get to Mexico as the biggest mark-ups come from the street-selling level. Some of this money goes towards material wealth for the cartels and their lieutenants. But an enormous amount is laundered via U.S. banks, particularly in Texas, and through tax havens like Panama. Money is also laundered through real estate and shell companies all over the world.

ME: Can you describe the process in which people get involved with the cartels?

IG: It starts with an absence of government, an absence of wealth and an absence of family. With these three things, and the pull of easy money from (at first) petty crime, kids get involved. It usually starts with street gangs, then kids will be given a phone, a $50 weekly salary and told to stand guard on the corner as a kind of sentry, a halcón, before they’re moved to higher forms of crime, be it moving drugs or el sicariato (hitmen). And then the police are an active arm of the cartels in many areas.

ME: When you investigate in these dangerous areas, do you tell people you’re a journalist?

IG: Yes, always. I don’t want anyone to think I’m working for a rival cartel, or the DEA [U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration]. But reporting on organized crime can offer a strange protection. If I’m interviewing the head of the Red Command in Rio [de Janeiro], no one is going to hold me up because they know I’m with “them.” They also don’t want the trouble of robbing some gringo and having the whole police force roll up, guns blazing.

ME: But journalists are targeted by the cartels in Mexico?

IG: It’s usually for a specific, terrifyingly petty reason. Sometimes it’s for publishing something they don’t like. A co-worker of mine was killed for publishing an op-ed by a grieving mother which called the cartels cowards. It can also be for not covering a story they want you to cover, such as an example murder. A Juárez newspaper once published a chilling headline, directed towards the cartels, titled ‘¿Qué quiere de nosotros?’ (What do you want from us?)

ME: I’m sure many newspapers back off. Are there any you respect for not doing so?

Yes many. El RíoDoce in Sinaloa, for example, after my friend Javier Valdez was killed in 2017.

ME: When have you felt most in danger?

IG: There was one time in Michoacán, when cartel members dressed as autodefensas [self-defense forces] thought I was a DEA agent and threatened me with a grenade. Another in Tabasco when the Jalisco cartel told me they were going to raid my hotel for potential ransom victims. Another when I managed to pull over just a few miles before a cartel roadblock in Coahuila. The list goes on . . . .

ME: If you were to offer a child in Sinaloa a “Chapo” or a Che Guevara belt buckle, which would they choose?

Oh, Chapo every time. But the question of ideology is a pertinent one. While many cartels don’t have a political ideology, they do have strange rituals. For instance, Los Zetas take the Marines’ philosophy of “never leave a man behind” to new levels – “never leave the dead behind” – and steal back their fallen brothers from morgues.

Many cartel leaders, such as [former Familia Michoacana boss] Nazario Moreno , are quasi-religious, or suffer from a type of Jerusalem Syndrome in which they think themselves gods. There’s also a Robin Hood angle – standing up for the little man and the poor, which is celebrated by the narcocorridos.

ME: Okay, I’m giving you a magic wand. How would you attempt to solve the narco problem?

IG: First, drug policy reform. We need to accept drug policy is failing. It should be about reducing the tens of billions of dollars that go to criminals. There are two areas of tragedy: the people dying of overdoses, and the criminals being funded to slaughter each other, as well as their fellow citizens.

With drugs that are problematic to legalize, such as heroin, you need rehabilitation, because both the money and the overdose deaths are about addicts. Other drugs, such as cocaine, which are taken more casually, I would consider decriminalizing, or even legalizing. Certainly, I think marijuana should be legalized.

Secondly, you have to fight for the hearts and minds of the young people who are recruited into cartels. Society needs to offer something to these children, with funding for social work. Wealth inequality also breeds crime. It’s only after areas are ghettoized that cartels have room to breathe.

Thirdly, how do you build a police force that’s trusted? It’s very hard to find a blueprint for this. Nicaragua, despite its poverty, is supposed to have a police force that’s resistant to the insurgency of gangs, particularly in areas where they fought the Contras, but trust has been undermined recently. Cuba has a lot less crime than its neighbours but it’s a fairly authoritarian society. Countries like Chile, too, but I’d put that down to per-capita wealth.

ME: Would you halt the flow of guns into Mexico from the USA?

IG: I would try. Most of the guns used by the cartels are purchased in the U.S. I don’t see banning guns in the U.S. as realistic, but there are many other steps you can take. We need to reduce the number of guns coming into Mexico.

ME: What’s your opinion, so far, on López Obrador’s presidency?

IG: When he was elected there was a moment of hope for change. It was the biggest win for a president in years. However, his first eight months have been disappointing. You’ve had an increase in violence and a flat economy. You can’t pin this all on AMLO’s presidency because these things are eternally complex and can’t be solved overnight, but his strategies haven’t been clear, or successful. The new National Guard, for instance, hasn’t avoided corruption in the way López Obrador thought it would.

ME: Finally, are you optimistic for the future?

IG: I really can’t say. It’s not my job to be optimistic.