Twenty-five years ago today, Luis Donaldo Colosio Murrieta, presidential candidate for the then-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), was assassinated at a campaign rally in Tijuana, Baja California.

Only one man, Mario Aburto Martínez, was convicted of Colosio’s murder. He was sentenced to 42 years in prison.

But millions of Mexicans doubted or outright rejected that he was the mastermind of, or even committed, the crime.

Twenty-five years later, people continue to deny that Aburto is the true culprit. Most fingers instead point at the PRI – an inside job against a candidate who was trying to shake things up a little too much and made some powerful enemies in the process.

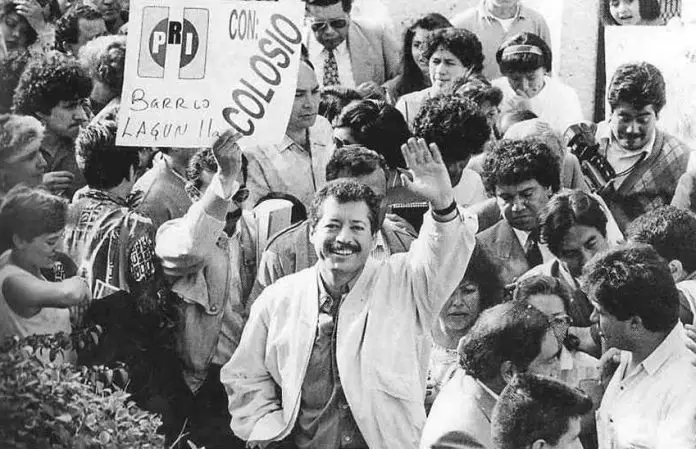

On March 23, 1994, Colosio arrived in Tijuana on the campaign trail for that year’s presidential election, which he was almost certain to win.

According to journalists covering the campaign, the rally in the poor Tijuana neighborhood of Lomas Taurinas at which Colosio was shot was not originally on the candidate’s itinerary for that day.

At around 4:00pm, Colosio arrived – without an excessive security entourage – at the venue that would host the rally.

He appeared to be in a good mood, smiling and greeting the people who had gathered to hear him speak. Just over an hour later, he was shot twice, first in the head and seconds later in the abdomen.

The 44-year-old candidate was rushed to a Tijuana hospital but hours later he was pronounced dead.

A man – supposedly Aburto – was arrested at the scene of the crime but many people believe that a different man – the real Aburto – was convicted of the crime. In other words, the killer was replaced with an innocent man.

After a long and seemingly comprehensive investigation – and a confession by Aburto – the federal government declared that the 22-year-old was the sole culprit, although many people suspected that there were two gunmen.

Miguel Montes, the first of five special prosecutors who worked on the case, believed that Aburto had not acted alone based on the fact that Colosio was shot twice and that the bullets had apparently come from different directions.

Four other men, including former police officer Vicente Mayoral Valenzuela and Jorge Antonio Sánchez Ortega, an intelligence agent for the now-disbanded Center for Investigation and National Security (Cisen), were arrested in connection with the assassination.

But the hypothesis that more than one person was responsible for the murder was abandoned after Aburto admitted that he acted alone.

Building the case against him, authorities established that Aburto suffered from borderline personality disorder, a condition they contended contributed to his actions.

Olga Islas de González Mariscal took over responsibility for the investigation in July 1994 after Montes resigned and five months later she declared that Aburto had indeed acted alone.

Another theory regarding Colosio’s murder is that organized crime was responsible.

Guillermo González Calderoni, a former police commander, said in a 1998 television interview that the Arrellano-Félix Cartel was responsible for the murder.

A total of 29 different versions of events involving organized crime were considered by the federal attorney general’s office, including one that Colosio’s campaign was funded by Colombian drug money or by now-convicted drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

According to three versions of events, Aburto had links to drug trafficking organizations.

However, authorities said there was insufficient proof to substantiate any of the organized crime hypotheses.

Yet another theory contends that Colosio’s own party was involved.

On March 6, 1994, Colosio gave a speech in front of the Monument to the Mexican Revolution in Mexico City in which he spoke of social problems in Mexico and said that corruption and impunity existed within the PRI.

“I see a Mexico that is hungry and with a thirst for justice, a Mexico of mistreated people . . . women and men afflicted by abuses of the authorities or by the arrogance of government offices . . . I declare that I want to be the president of Mexico to lead a new stage of change in Mexico,” he said.

The speech is considered the moment in which Colosio broke ranks with then president Carlos Salinas de Gortari and signaled that he would take the party and the country in a different direction.

Following the speech, there was speculation that Colosio would be replaced as the PRI’s candidate by former cabinet secretary Manuel Camacho Solís. However, just 17 days after the controversial speech, Colosio was murdered.

Ernesto Zedillo, Colosio’s campaign manager, was chosen as the new PRI candidate and went on to win the election and serve as president until the year 2000.

The theory that the PRI was the mastermind of Colosio’s murder – and that president Salinas perhaps even ordered it – is the most widely believed by Mexicans.

The candidate’s father, former PRI senator Luis Colosio, maintained until his death in 2010 that people in power were responsible for his son’s death.

But authorities ultimately concluded that the political motive for the crime was not supported.

According to Laura Sánchez Ley, a journalist who has investigated the Colosio case for years and wrote a book about it, Aburto wasn’t the man authorities painted him to be.

Sánchez said that she concluded that Aburto most likely wasn’t “the crazy man” that authorities said he was.

She also said she received information showing that the government used shocking tactics to coerce Aburto’s family into confessing that they knew that he planned to kill Colosio.

“It turns out that during the days after the murder, Mario Aburto’s family started to be terrorized by the Mexican government so that they would confess that they knew that Mario would commit the murder . . . Authorities physically and sexually abused the younger girls in the family, they started to terrorize them at night by shooting at their house,” she said.

Sánchez, along with the anti-graft group Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (MCCI), with which she collaborates, won a legal battle late last month that enabled the 25-year-old investigation into Colosio’s murder to be declassified.

She said there are “a lot of contradictions” in the information contained in the 10,000-page file that calls the official version of events into question.

“There were contradictions in the declarations” made by witnesses, Sánchez said, explaining that seven of nine police officers who made statements weren’t at the scene of the crime.

“There were contradictions in the big truths” proffered by authorities that “make you reconsider how certain the truth that they told us [really] is,” she added.

At President López Obrador’s daily press conference yesterday, United States reporter Jovanny Rivera Huerta shared a letter written by Aburto’s parents, who fled to the U.S. after Colosio’s murder.

“They ask you to re-open the Colosio case. The have a lot of faith in your word and in the transparency you have given the government and the country,” he said.

The president accepted the letter and said that he would read it and pass it on to other officials to see “what comes of it from a legal point of view.”

López Obrador urged authorities to keep investigating the case before declaring “I’m really sorry and I always regret the murder . . .”

Colosio’s family were among about 100 people who marched in his memory today in his home town of Magdalena de Kino, Sonora. The parade was headed by his son, Luis Donaldo Colosio Riojas and his family and two of the assassination victim’s sisters.