As COP30 opens Monday in the Brazilian city of Belém, Mexico’s national climate plan still faces criticism, but there is also reason to hope that President Claudia Sheinbaum will continue to strengthen Mexico’s climate change commitments at this year’s conference. She has much to undo.

In 2022, the government of former president Manuel Andrés López Obrador — frequently referred to as AMLO — weakened Mexico’s original 2020 commitments to environmental institutions and infrastructures while boosting fossil fuels usage, a breach of both Mexican law and the Paris Agreement.

Critics also cried foul on Mexico’s current National Determined Contributions (NDCs) commitment, which they say gives the impression of climate change ambition but is an illusion. They have accused the former administration of manipulating the math to make Mexico’s NDCs appear more effective than they are in reality.

Mexico’s behavior at COP30 is likely to reveal where Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum — who has a background as a climate scientist — is going long-term in addressing global climate change. She already took some steps at COP29 to strengthen Mexico’s commitments, so there is reason to believe she may authorize further steps forward.

Sheinbaum, however, is not one of the world leaders attending COP30. Like last year, she has sent her Environment Minister, Alicia Bárcena.

What is COP?

The annual Conference of the Parties (COP) is an international summit organized by the United Nations, involving the 198 parties (mostly nation-states) that agreed to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 1992 international treaty that was the foundation for subsequent international agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol.

The UNFCCC’s primary objectives are the global stabilization of greenhouse gas emissions and finding sustainable solutions to prevent the consequences of human-induced global warming.

The annual COP summit — attended each year by world leaders, politicians, U.N. delegates, scientists and activists — is where the UNFCCC’s signatory parties negotiate new climate-change agreements and also hold each other accountable to fulfilling past commitments.

This year’s conference is when the parties, including Mexico, are expected to present their updated national climate plans for 2035 under the 2015 Paris Agreement, which committed parties to a goal of collectively limiting global temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius — and ideally 1.5 C.

Mexico was one of many countries to miss the formal deadline to submit its climate plan in February.

What did countries pledge at COP29?

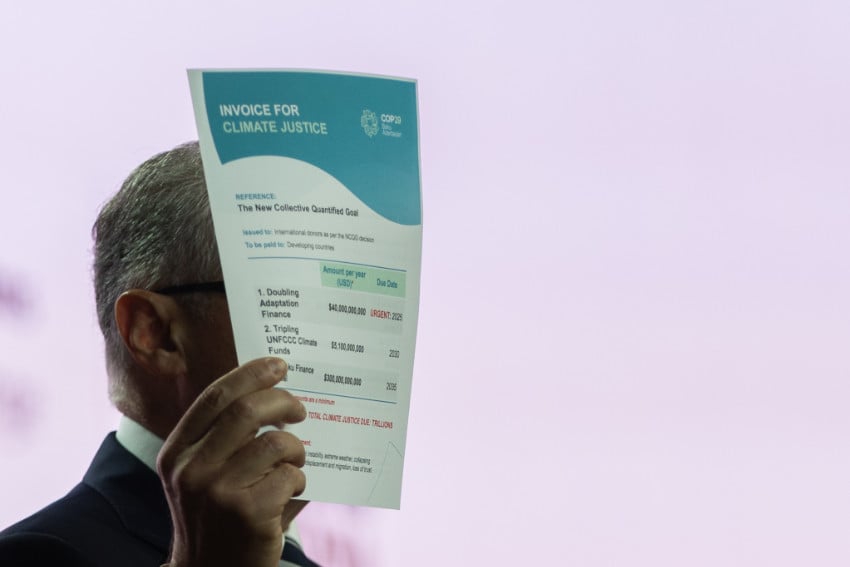

At COP29, which took place in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, the parties agreed to the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), allocating an annual collective US $300 billion in international climate financing to developing countries by 2035.

The purpose of this financing is to assist developing countries reach their global climate goals and help them implement strategies to protect from floods, storms and rising temperatures. The financing will also help lower-income countries fund the switch to clean energy and recover from disasters and losses caused by climate change.

The NCQG is to be implemented through these methods:

- Bilateral finance, a type of corporate lending that involves a single lender and a single borrower.

- Multilateral finance, which is corporate lending involving a single borrower but multiple lenders.

- Private finance mobilized by the public sector — essentially, incentives to invest offered to private companies by a government.

In signing on to the NCQG, contributing nations agreed to the possibility of “alternative sources,” such as international carbon taxes or solidarity levies, that is generating funding by imposing taxes on business sectors that benefit from globalization and generate significant environmental or social costs.

While marking a threefold increase in money from the previous year, many observers widely regarded the agreement reached at COP29 — known as the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG) — as falling far short of the figure required for the clean-energy sector’s growth and the effective and sustainable protection of people and the environment. Experts calculated this at US $1.3 trillion by 2035 — an amount that COP29 did set as a looser, less binding goal.

Many have also deemed the scaling up of private investment critical if we are to close the $1 trillion gap between the agreed-upon targets and the recommended ones.

AMLO’s numbers game

As stated above, Mexico’s current climate plan faces criticism, thanks to the actions of the previous government. To make its emission reduction percentage target appear higher, López Obrador’s government changed the emissions baseline. This, said activists, gave the impression that Mexico’s emission reduction percentage target was actually higher than it was, when in fact, net emissions would rise.

Beyond this, NGOs such as Oxfam Mexico have warned of Mexico’s persistent disparity between the authorization of particular laws on climate and the budget Mexico says it’s prepared to commit to the cause. And the Sustainable Finance Index has documented that only 0.47% of the country’s budget goes to climate mitigation.

While Mexico’s calls for humanistic climate change policies were received well enough at COP29, there is currently discussion among observers that President Sheinbaum needs to prove her commitment to climate change with real figures and substantive action, not just words.

The Escazú Agreement

One area in which Mexico could do that is by pushing for the ratification of the Escazú Agreement, a landmark treaty that stemmed from the Rio+20 Conference, pioneering “access to justice” and the legal protection of environmental defenders.

According to the NGO Global Witness, at least 196 environmental activists were killed in 2023 alone, with 85% of those in Latin America. Eighteen of those were in Mexico. The reality is that this number is likely far higher as many attacks on environmental activists fly under the radar or go unpunished.

The Agreement’s ratification could ensure more safety and justice for land defenders in Mexico and across the Americas. Mexico supporting the Escazú Agreement at COP30 would be a way for Sheinbaum to send a powerful statement in support of Mexico’s environmental activists and show that addressing climate change is important to her administration.

Preparations for COP30

In August, representatives from 22 Latin American and Caribbean countries attended a preparatory meeting for COP30, organized by the Mexican government and the COP30 president, André Corrêa do Lago. The goal of the meeting, dubbed The Latin American and Caribbean Ministers’ Meeting for Implementation of Regional Climate Action, was to fortify regional coordination at COP30 in the face of the structural and historical climate inequalities faced by the region’s countries.

The notion of climate inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean is nothing new. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the region accounts for just 11.3% of greenhouse gas emissions, yet 75% of its nations are facing the brunt of more extreme and frequent climate events. However, the region still needs to increase its expenditures significantly to meet its climate commitments.

“Faced with the multiple crises we are experiencing, it is more important than ever to engage in dialogue on our common challenges,” Bárcena said at this meeting, which ended with a declaration by the parties that could bode well for Mexico’s performance at COP30.

In that declaration, the countries expressed support for the Paris Agreement’s NDCs and the need to transition away from nonrenewable energies. The declaration also highlighted the importance of respecting and empowering Indigenous peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants, as well as supporting climate-affected human rights.

In addition to acknowledging the parties’ agreement that climate change action must address economic, social and environmental inequalities, Sheinbaum identified a fourth pillar necessary for sustainable development: “the sovereignty and self-determination of peoples.”

What can we expect at COP30?

As laid out by the U.N., COP30 will focus on:

- The efforts needed to limit the global temperature increase to at least 1.5 C.

- The presentation of new national action plans (NDCs).

- The progress on the monetary pledges made at COP29.

In regard to the NCQG, COP30 will see the delegates finalize the Baku-to-Belém Roadmap to strategize how the finance goal will be mobilized and monitored. Yet, what seems to be clear is the need for accountability and true commitment to cover the costs of loss and damage due to climate change in developing countries.

Brazil’s Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, Marina Silva, has designated COP30 as “the COP of implementation.” Promises of budgets, policies and protection now need to be enacted on the ground.

Mexico had no official space at COP29, but this year, delegates are changing that: Mexico will have a 200-square-meter National Pavilion at the conference, with a press room to boost media coverage on sustainability. Climate investment initiatives and opportunities will be at the forefront: Mexico’s government has already promised over $32 billion of public investment in renewable energy infrastructure.

A promising start, but while Mexico has also recently made progress on its National Restoration Plan — 30% of Mexico’s land is currently degraded — Climate Action Tracker still terms Mexico’s overall climate progress as “critically insufficient.”

COP30 will hopefully encourage Mexico to increase its financial commitment to its climate goals across public and private sectors — and strengthen its participatory environmental governance with non-state players and Indigenous communities. And based on Sheinbaum and Barcena’s statements at the regional meeting in August and since, there’s hope to be had that Mexico is turning toward a more environmentally proactive course.

But phasing out fossil fuels by 2050, scaling up climate finance for people and the environment and implementing strategies to build a more climate-resilient society remain critical goals for Mexico. These next 12 days of COP30 are likely to tell the world whether Mexico plans to truly step up to the challenges of climate change or continue to rely on numbers games.

Millie Deere is a freelance journalist