Bernal, a small pueblo in Querétaro, has a lot going for it. It’s designated as a Pueblo Mágico, or Magical Town, and it’s easy to see why when you walk down its cobblestone streets lined with colorfully painted buildings and past shops and carts featuring local foods and crafts.

Bernal features a museum with 300 masks from all over Mexico and the Museo de Dulces (Sweets Museum), which highlights the locally made cajeta (caramel). Looming over it all is Peña de Bernal, the huge monolith.

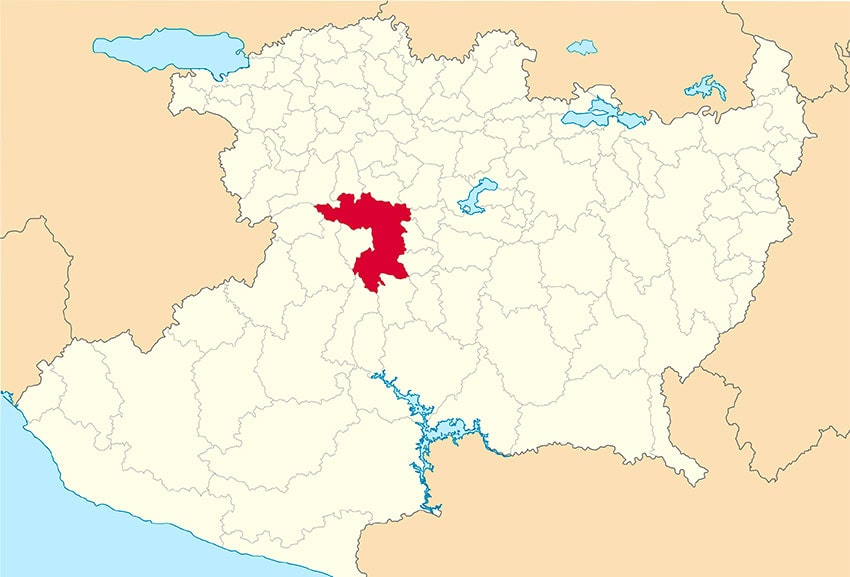

It’s an easy 40-minute ride from the capital city of Querétaro and is located along the wine and cheese route.

Bernal’s a very walkable pueblo, and there are lots of places to stop for food, drinks or shopping. It wasn’t overly crowded on the Friday in May that I was there, but I’m told it does get packed on most weekends.

Unfortunately, the Museo de la Mascara, the mask museum, was still closed in May, and the Museo de Dulces didn’t open until 1 p.m., and I had to leave Bernal before then. But the first-floor store was open and selling all sorts of locally-made cajeta treats.

“Don Julio Rodríguez Velázquez started making cajeta and traditional sweets in 1961,” said Maricela Luna, who was running the store’s counter. “We have the only factory making cajeta in the pueblo.”

She said the most popular treats are the natillas, little squares of cajeta with toppings like sesame, nuts or amaranth. “Our products are artisanal,” she added.

There are too many other sweets to name. If you visit, just know that it can be difficult to show any type of restraint; I wasn’t able to.

There’s been some confusion as to the correct height of Peña de Bernal, the monolith. Some reports list it as 288 meters (945 feet) while others claim it’s 360 meters (1,181 feet). Either of these would make it the third tallest monolith in the world, behind the Rock of Gibraltar and Brazil’s Sugarloaf Mountain.

But according to an article in the journal Geosphere, more accurate measurements found that at its highest point, Peña de Bernal is 433 meters (1,421 feet) tall, making it the tallest monolith in the world. I’m sure there will continue to be debate but there’s one thing that’s certain: that thing is big.

There’s a trail leading up on one side of the rock and, although not dangerous, it isn’t for the faint of heart, either. There are some fairly steep — but thankfully short — climbs along its length, and footing is dicey in some spots.

One hiking website said it’s a Class II trail, one that requires walking over loose stones or sometimes needing to use your hands for balance in spots, something I found to be true. Further on, it turns into a Class III trail, requiring a lot more skill and even further, Class IV, which requires a guide and special hiking gear.

Tiffany Pence, my hiking partner, suggested we stop before reaching the more challenging sections, and believing that discretion is the better part of valor, I agreed.

On the way down, we passed Peter Rochac, a 23-year-old Texan, and a couple of other people who were climbing up the sheer face of the monolith that, to me, looked like the Dawn Wall at Yosemite.

“This is a moderate climb,” said Rochac, smiling when I must have looked incredulous. “It’s called sport climbing.” He pointed to a small ledge above us. “The anchors are pre-set, and it won’t take more than five minutes to get to that.”

There’s also a more difficult section he planned on tackling with Alfredo Pérez, his guide from Aventuras Denali. Pérez handed me his business card, and printed on it was the question, “When was the last time you did something for the first time?”

The card advertised rappelling, bungee-jumping and some other rather extreme sports I’m thankfully too old to try for the first time. But I’ve kept his card in case I get that promised second childhood.

Tiffany told me that it’s a tradition to drink a michelada, beer mixed with — at least — lime and hot sauce (the recipe varies widely) and served in a glass whose rim is dipped in salt. It was early in the day, so we skipped that, but we did feast on another local tradition: blue corn gorditas at El Negrito Gorditas y Micheladas.

Gorditas are made from masa (corn meal) and are large, thick, round and stuffed with any number of tasty foods. I’m planning on a return trip to Bernal and will hike Peña de Bernal later in the day just so I can have a michelada and two gorditas.

Querétaro is considered to be the Americas’ first winemaking region, with the first vines planted by the Spanish in 1531. Bernal’s located at the upper edge of the region, and it’s definitely worth taking the time to visit some of the nearby vineyards and artisanal cheese makers, several of which are located just south of the pueblo.

More information and locations can be found at the website for the Asociación de Vitivinicultores de Querétaro.

And no trip to Bernal is complete without sampling some famed Nun Farts.

There were signs in front of a number of stores in the pueblo advertising the Pedos de Monja. I’d never heard of them before and didn’t even know what the phrase meant, so I asked Tiffany what they were. She explained that they are a candy famous throughout Querétaro. My curiosity piqued, we entered Mercadito Las Bugambilias.

“Pedos de Monja is originally an Italian recipe,” explained Mauricio Ramos, the store’s owner. “In Italy, it is a small cookie, and it is called Petto di monca, which means ‘Nun’s Chest.’”

Apparently, an Italian chef in Barcelona came up with the recipe and name sometime in the 19th century. I couldn’t find any information about why he decided to call them “Nun’s Chest.”

“The Spanish, they could not pronounce the Italian word petto, so they changed it to pedo,” Ramos said. “In Querétaro, we have our own recipe.”

The ones I ate in Bernal were delicious chocolate candies filled with almond paste. The slogan on the package was, “Más vale adentro que afuera” — better in than out. I agree.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.