The National Electoral Institute (INE) has barred two Morena party candidates for governor from contesting the June 6 elections in a move that is certain to inflame tensions between the agency and the ruling party.

The two are among several candidates, most of whom belong to Morena, who were disqualified because they failed to submit reports detailing their pre-campaign expenses.

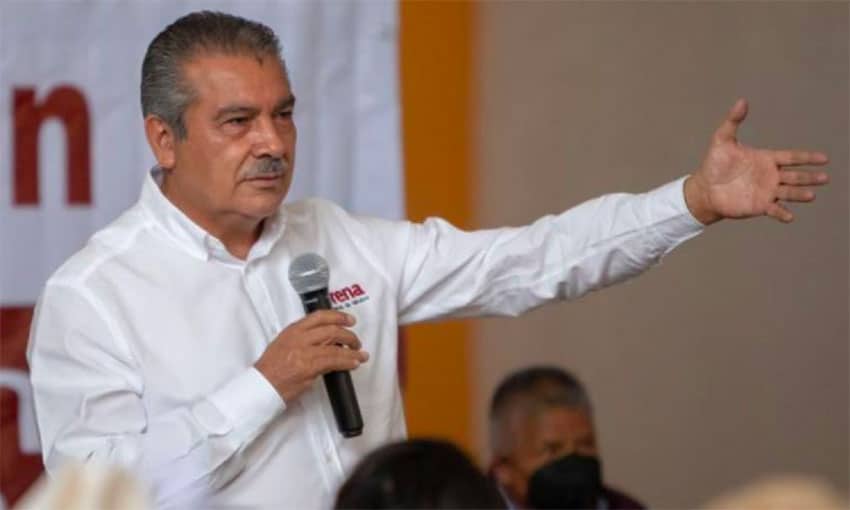

Out of the running unless a court rules otherwise are Félix Salgado, a former senator who won Morena’s nomination in Guerrero despite facing several accusations of rape, and Raúl Morón, an ex-senator who left his position as mayor of Morelia in January to contest the gubernatorial race in Michoacán.

A majority of INE councilors voted in favor of deregistering the candidates in a marathon meeting on Thursday. In the case of Salgado, seven councilors voted in favor of rejecting his candidacy while four opposed the move.

A majority of councilors also voted in favor of barring former Acapulco mayor Luis Walton, current Acapulco Mayor Adela Román and the federal government’s super-delegate in Guerrero, Pablo Amílcar Sandoval, from contesting the elections because they too failed to file spending reports. That means none of the three morenistas, as Morena party members and supporters are known, will be able to replace Salgado on the ballot in Guerrero.

In the case of Morón, six councilors supported the disqualification of his candidacy while five opposed it.

The INE also barred 61 candidates for mayor and federal deputy positions from running because they didn’t report their expenses or there were inconsistencies in the information they provided. At least 42 of the disqualified candidates were nominated by Morena, a party founded by President López Obrador.

INE councilor Adriana Favela noted that any person aspiring to be a candidate at an election must submit a pre-campaign expenses report to the Electoral Institute.

Morena said that in the cases of Salgado and Morón, there were no pre-campaign events and therefore there were no expenses to report.

However, councilor Jaime Rivera said it was proven that there were costs associated with Salgado’s participation in the pre-campaign process to seek Morena’s nomination. Councilor Claudia Zavala said that there is a reporting requirement even if no pre-campaign expenses were incurred.

Uuc-Kib Espadas, one of the INE councilors who voted against disqualifying the candidates for governor, said the punishment didn’t fit the crime, asserting that barring them from running in the election was an excessive penalty.

However, councilors who voted in favor asserted that while the punishment might seem excessive, the law stipulates that candidates who fail to report pre-campaign expenses must be disqualified from running. Espadas acknowledged that the INE hadn’t acted illegally and accepted that it is not biased.

The decision to reject the candidacies of the two aspirants for governor comes after INE’s audit committee warned in late February that there was a risk of Morena party candidates being disqualified because they hadn’t submitted spending and income reports.

On February 26, the INE general council issued fines for more than 7.1 million pesos (US $345,000) to numerous parties, including Morena, that had not filed expenses reports for their pre-candidates. It gave the parties five days to do so but many Morena candidates didn’t comply with the directive.

Salgado, whose candidacy was confirmed by Morena earlier this month after it completed a new selection process amid calls for the 64-year-old alleged rapist to be dumped, said Thursday – prior to the INE councilors voting to reject his candidacy – that he would fight any such move in the Federal Electoral Tribunal, adding that he would take his case to the Supreme Court if necessary.

In a Facebook post published early on Friday, Salgado asserted that the INE was “mistaken,” describing the decision to reject his candidacy as “objectionable and arbitrary.”

He also said that he was confident that the electoral court would overturn the decision and deliver justice. “We’re still in the fight. Everyone cheer up!” Salgado wrote.

Morón also said that he would challenge the INE decision in court.

“INE took an illegal decision. We will not allow it to trample on the will of our people; we will go to the electoral tribunal to defend democracy,” he wrote on Twitter.

President López Obrador took aim at the INE at his regular news conference on Friday, charging that it had become a “supreme conservative power.”

“It’s strange because it didn’t do it before, now it’s turned into the supreme conservative power, it now decides who is a candidate and who isn’t. It wasn’t like that before. Maybe they changed the laws or didn’t apply them before,” he said.