When Tatiana Clouthier, Mexico’s new economy minister, was in her 20s and finishing her first civil service job, she found out that she was on the lowest salary level of all her colleagues. “That was my first shock of understanding what it means to be a woman and to earn less,” she says, in a video interview with the Financial Times (FT).

A dozen years later, by then a member of Congress, she was warned by a male colleague about her career: “Your children are small and your husband is very handsome and young — you’ll put your marriage at risk.”

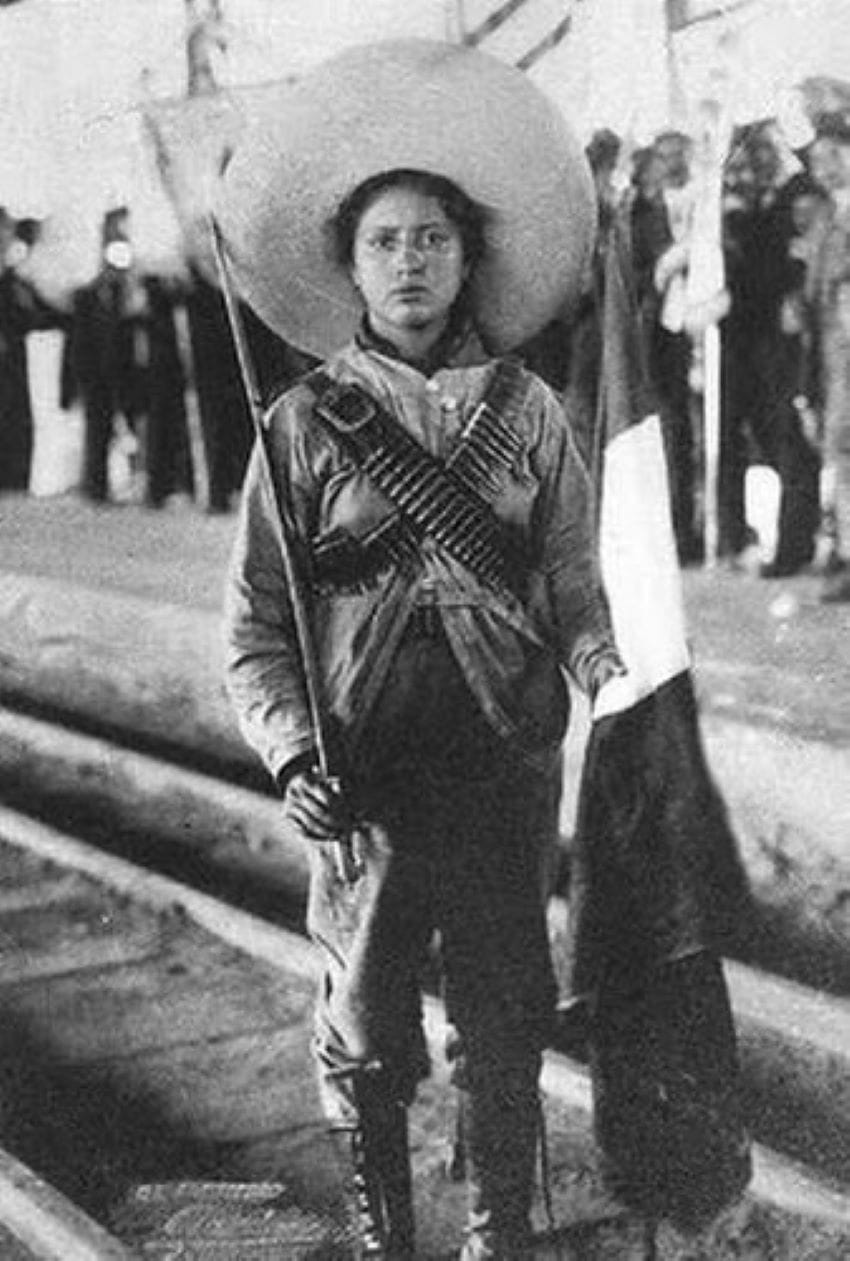

That was in the early years of the millennium, barely half a century since women won the right to vote in 1953. Macho Mexico has made progress since then.

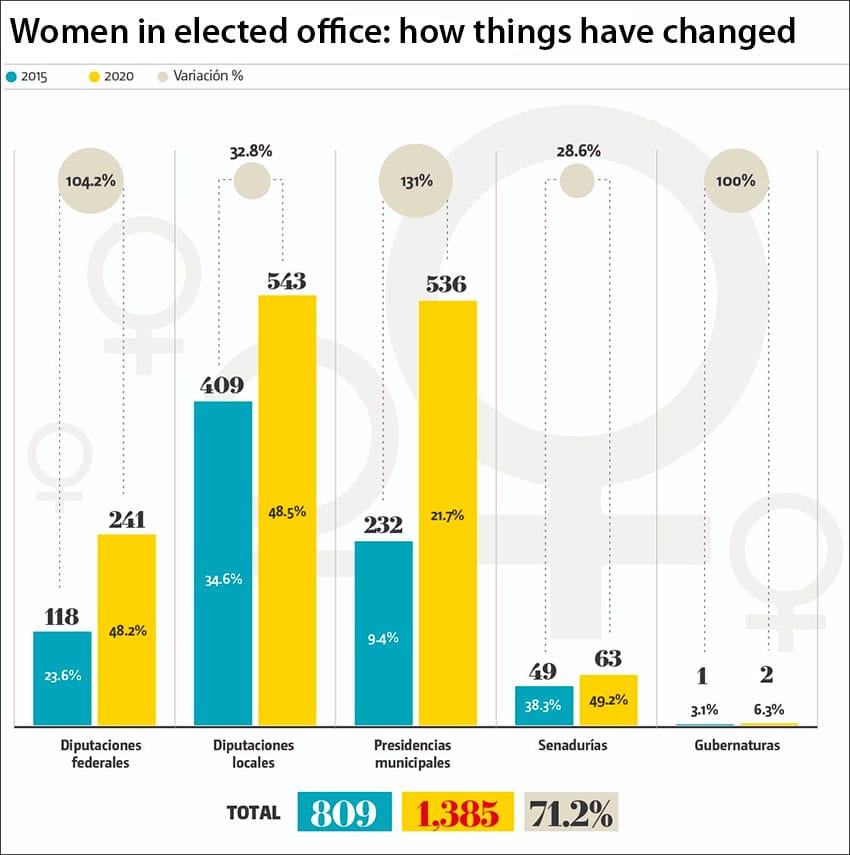

Women now hold nine of the 19 posts in Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government. Indeed, in June 2019, gender parity in Mexico’s government, Congress, judiciary, autonomous institutions and election candidacies was enshrined in the constitution. So, too, was “language that makes women visible and included.”

But even though Clouthier — who managed López Obrador’s triumphant presidential election campaign in 2018 — has experienced sexist values first hand, a recent verbal slip showed how deeply entrenched gender attitudes remain in Latin America’s second-biggest economy.

In a virtual news conference soon after starting her job in January, she referred to her female deputy, Luz María de la Mora, by her first name, and the diminutive “LuzMa.” She addressed her male deputy, Ernesto Acevedo, by the honorific “Doctor,” even though both officials have PhDs.

For feminists in Mexico, comments such as this prove that social change is sometimes only superficial — and that, despite major strides, there is still a long way to go.

Studies show Mexican women want jobs, help with their caregiving roles, and freedom from violence, Clouthier says. Yet, on all three counts, results are mixed — and Covid-19 has made things tougher still.

“Women are the most affected by Covid and super vulnerable in employment terms,” says Fatima Masse, director of inclusive society at IMCO, a leading think tank.

She notes that 73% of women who lost their job at the start of the pandemic are back at work, but 57% of job losses in January compared with December were among women and “nearly 800,000 women who had recovered their jobs in December 2020 lost them again in January 2021.”

As in many countries, Mexican women bear the brunt of caring for children and elderly or ill relatives. López Obrador was criticized when he took office for scrapping subsidies to children’s nurseries and giving women cash transfers instead, which did not always covering nursery charges.

Clouthier says a law designed to ensure the right to “dignified care” was passed in the lower house of Congress last November, but critics say no new funds or institutions have been proposed to support this.

“They consider that cash transfers are like offering a welfare state — that’s inaccurate,” Masse says.

Violence is one of the thorniest issues holding back women’s participation in the workforce. Women who have jobs outside the home can more easily escape violence, Clouthier says, and she is offering 20,000 micro-credits worth $1,200 specifically to women at the helm of small businesses.

But in the first nine months of 2020, nearly one in 10 homes reported some kind of domestic violence in a country where two-thirds of women have suffered violence — 44% at the hands of their partners. Some 11 women a day are murdered. A recent study found 24% of crimes classified as femicide between 2012 and 2018 led to convictions, but more than twice as many murders of women were not classed as femicide, suggesting near total impunity.

López Obrador has ignited a storm of protest for refusing to criticize his party’s candidate for governor of the state of Guerrero in the June midterm elections, even though Félix Salgado Macedonio faces multiple allegations of rape — including one by a woman who says he drugged her first.

Women were further dismayed when López Obrador admitted he had been clueless about what women meant by a social media campaign urging “break the pact” — a reference to patriarchy — and had needed to ask his wife.

“He’s the head of state. Words build realities,” says Arussi Unda, spokeswoman for Brujas del Mar, a feminist collective which rose to prominence last year when it organized “a day without women” strike.

Statistics show that women work more than men, earn less and struggle to climb the corporate ladder in Mexico.

When IMCO — the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness — analyzed 155 listed companies, it found that Mexico’s 9% female board representation was the lowest among similar economies or European nations. Only two chief executives were women.

IMCO has indicated that Mexico’s GDP would increase by 15% by 2030 if 8.2 million more women joined the workforce. The country currently has one of the world’s lowest rates of female participation in the workforce, a little above Bangladesh but below Romania and Kyrgyzstan.

Clouthier says she is working with the U.K. government on a pilot scheme to analyze Mexico’s gender pay gap. Graciela Márquez, her predecessor in the job, also a woman, launched schemes to help women export artisanal products, but Clouthier acknowledged progress so far is “baby steps.”

She also acknowledges that coding, e-commerce or tech skills are vital for women seeking to re-enter employment. However, encouraging girls into science, maths, technology, engineering and technology subjects does not yet figure on the education ministry’s radar.

So when La-Lista, a new media venture, kicked off in January, chief executive Bárbara Anderson made sure the first story was about female role models — the 14 women who made Mexico’s access to Covid-19 vaccines possible.

“The credit went to the men but the success of getting the vaccines depended on these 14 women, some of whom had to be connecting to their computers at 2 a.m., when their kids were in bed, to talk to officials in other countries,” she told the FT.

“Cultural change is very slow,” says Marta Lamas, a professor at National Autonomous University, who has fought for women’s rights for half a century. Or as Unda puts it, particularly regarding gender violence, “I don’t think we’re going backward but we’re meeting a lot of resistance ahead.”

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.