The coronavirus pandemic serves as proof that the “neoliberal” economic model has failed, according to President López Obrador.

In a six-page dispatch entitled Some lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic, the president writes that “the coronavirus is not responsible for the economic catastrophe” but rather “the pandemic has … exposed the failure of the neoliberal model in the world.”

In Mexico, López Obrador writes, governments in power during the neoliberal era – a period he defines as the 36 years before he took office in late 2018 – failed to adequately fund public universities, violating young people’s right to education and leaving the country with an insufficient number of doctors and nurses “to attend to the nation’s health needs.”

He also says that a lack of hospital beds, ventilators and personal protective equipment for health workers is a product of the years of neoliberalism in Mexico.

In addition, López Obrador blames neoliberal governments for failing to respond over a period of decades to the widespread prevalence of health problems that make many people more susceptible to Covid-19.

“Perhaps the greatest indifference or irresponsibility of governments that the coronavirus [pandemic] has exposed is the disregard, for decades, of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and kidney problems,” he writes.

“In our country, the pandemic has showed that the most affected people have been those with the above-mentioned chronic diseases.”

The neoliberal model, the president charges, is only concerned with economic growth “without caring about the wellbeing of the people” or the environmental damage that the pursuit of endless growth causes.

Another failing exposed by the coronavirus pandemic, López Obrador adds, is that there is “scant solidarity” between the nations of the world when it comes to purchasing medical equipment and medicines.

“A ventilator that cost on average US $10,000 before Covid-19 is now sold for up to $100,000” he writes. “The worst thing is that, due to the shortage, there is stockpiling [of medical equipment and supplies] both by governments and the companies that produce them.”

López Obrador asserts that the coronavirus pandemic “has come to demonstrate that the neoliberal model is in its terminal phase.”

“As a result, it’s time to create new forms of political, economic and social cohesion, putting definitively to one side the commercial, individualistic and unsupportive approach that has been predominant during the last four decades. … The unstoppable expansion of predatory neoliberalism … [has caused] exploitation, looting [of public coffers], environmental devastation, pathological eating habits, organized crime, social and family breakdown and a generalized loss of values,” he writes.

“There has been no interest in providing people with drinking water, electricity, schools, clinics, roads and telecommunications.”

At the end of his dispatch, the president outlines eight “basic lessons” he has drawn from the coronavirus pandemic.

López Obrador writes that the strengthening of public health systems is essential and that attending to the “serious problem” of chronic diseases is urgent.

He says that “a more caring world” in which medical resources are shared more equitably is essential and that the United Nations and the World Health Organization “must immediately summon the government and scientists of the world to create vaccines against the coronavirus and other ills.”

The president also writes that the economic model that “creates wealth without wellbeing” must be disposed of, asserting that it is the responsibility of the state to reduce social inequalities. His sixth “lesson” is that cultural, moral and spiritual values must be strengthened and that the family should be recognized as “the best social security institution.”

López Obrador argues that the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the G20 need to become “true promoters of cooperation for the development and wellbeing of people and nations.”

The final “lesson” the president draws from the pandemic is that the ideas and actions of the governments of the world should be guided more by “humanitarian principles” than economic and personal interests.

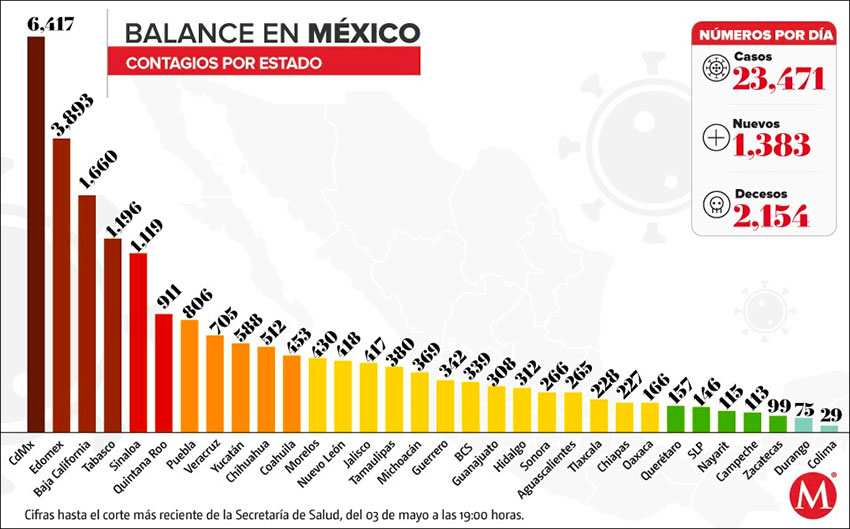

“The still ongoing pandemic will leave us with hundreds of thousands of irreparable absences [deaths] and a … severely diminished economy” he writes.

“In many senses, we will have to apply ourselves to the task of rebuilding the world,” López Obrador adds, asserting that health care has to be a “collective task” and that all people around the world “belong to the same family – humanity.”

Mexico News Daily