At least four vacationers at a luxury resort in Nayarit escaped a government-imposed coronavirus quarantine via helicopter on Wednesday, says César Guzmán Rangel, head of Civil Protection in that state.

The tourists from Guadalajara were among some 220 visitors at the beachfront resort Los Veneros. The quarantine was imposed when government officials learned that two of the guests at the luxury condominium development had tested positive for coronavirus before arriving at the resort, and the remaining residents refused to be tested.

The quarantine was enforced by the placement of a sanitary barrier to prevent the spread of the virus to other guests, workers and residents of Bahía de Banderas.

An official statement on the installation of the barrier claimed that “all health protocols are being followed, and it means that the 220 people who vacation in this luxury housing complex will be in quarantine; that is, no one can leave for at least 10 days, which is the minimum time to complete the 14 days of isolation that is required to rule out incubation of the disease.”

Los Veneros — where rentals go for around US $1,400 a night — is located on the road to Punta Mita and under normal circumstances, guests are drawn to its “37 enchanted acres along a stretch of almost 1,500 feet of white sandy beach frontage at renowned Playa de Estiladeras,” the resort’s website reads. “Entry is via gated access, with 24-hour welcome and security staff. Recreational amenities currently include inviting swimming pools, a chic oceanfront Beach Club with bar and grill, fitness, wellness and spa services, and an ocean activities center.”

Guzmán Rangel noted that, despite the breach on Wednesday, most of those quarantined supported the measure. “Most of those inside Los Veneros are in favor of what is being done to avoid contagion or to find out if they, too, have already been infected with this virus,” he said.

Governor Antonio Echevarría Garcia did not hide his contempt earlier this week for the two tourists who decided to continue with their vacation plans — it is Easter Week in Mexico — after testing positive for the virus. Tourists “are always welcome,” he said, “but not if they infect our people.”

In a Facebook post, the governor stated that he intended on winning what he called a war against coronavirus, and he would ask the state’s attorney general for help in dealing with those who refuse to abide by social distancing measures.

“If we have to bend the law a little to save the lives of the residents of Nayarit, I am going to risk it,” he said.

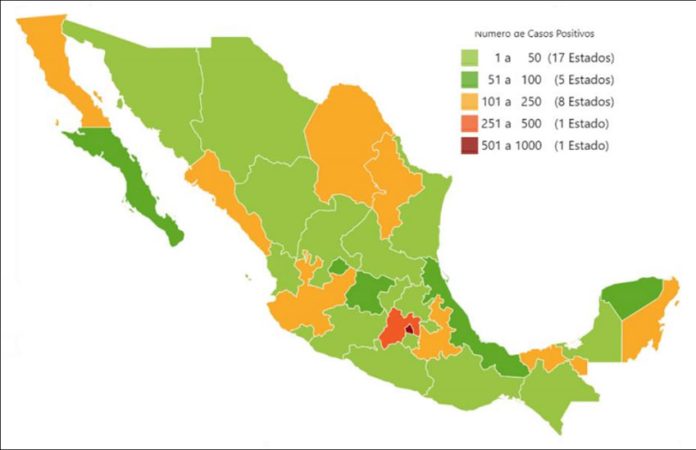

Nayarit currently has 18 confirmed cases of coronavirus and has recorded three deaths.

Source: La Reforma (sp)