When I was a teenager in Fort Worth, Texas, I spent a lot of time with a particular friend from school and his family.

The dad was fun and genuinely friendly, always ready with a fabulous dad joke. He also had some strange and quirky habits, such as standing in convenience stores while he munched on multiple hot dogs and getting up and marching straight into the kitchens of restaurants — a taboo he was simply unwilling to respect — to see what was going on if he felt the orders were taking too long.

I suppose he thought he was sparing the server of his complaints by bypassing the middleman. It was a real power move too, one that said, “Backstage is not off-limits to me.”

It’s hard to say what he might have concluded about how the people involved felt, and frankly, I’m embarrassed to ask him at this point. Those were the ʼ90s and more innocent times — at least in Texas.

I thought about that habit of his today as I was reading a piece in the New York Times about how customers in all types of industries in the United States have been increasingly — and in increasing numbers — devolving into tantrumming children when they don’t get what they want.

“It’s not just about them not finding the kind of cheese they wanted,” said one grocery store worker after witnessing a brie-induced meltdown.

People from the U.S. have a worldwide reputation of not taking “Sorry, you’re just not going to get what you want and there’s nothing you can do about it” for an answer. The positive side of that characteristic is the kind of relentless striving and achievement that we’re admired for.

This particular side of that relentless that we’re discussing, however, is the arrogance we’re derided for.

The article also made me think about my own recent experiences of frustration — some resolved, some not — here in Mexico, and how differently I handle them than my Mexican friends around me.

On more than one occasion, I’ve stood astonished and dumbstruck as I’ve observed people here simply let things go that would have had me in a literal fit, treating whatever had just happened as a true emergency.

Years ago, for example, one of my English students showed up to a party and didn’t say a word the entire time about the fact that the radio had just been stolen out of his car minutes before. He didn’t want to spoil the party. I’ve also watched people sit calmly and simply not eat their food because it was bad, refusing to say so to the waiter so as not to bother them.

I do send things back if they’re not good, though I have been told on more than one occasion that I’d still have to pay for what I ordered since I’d already eaten a few bites of it. My commitment to politeness keeps me from turning feral, but on the inside, I’m jumping up and down like Rumpelstiltskin.

Stolen vehicles, lost packages, overcharges, unsatisfactory service— they all result in a response of “Let’s just leave it; it’s not worth the conflict” after having thrown only about a tenth of the fit that I would have under the same circumstances.

From what is this Mexican Zen born? To be sure, I’ve known a few people in Mexico more Karenesque than their U.S. counterparts, but they’re mostly an anomaly and tend to be fairly well-off. That said, they’re vocal about dissatisfaction, so they obviously make a lot more noise than someone quietly walking away as they fume.

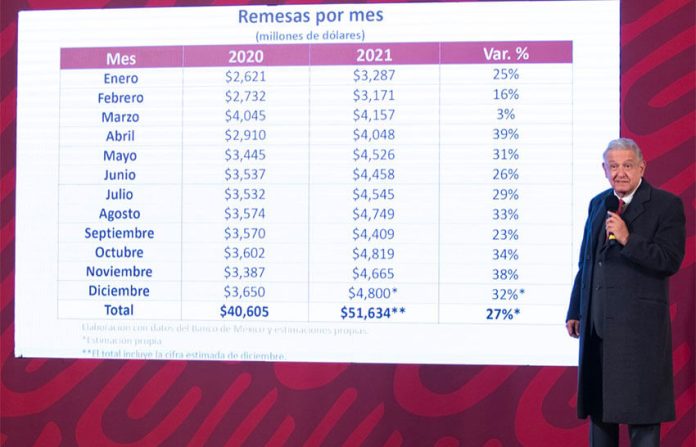

Surely it was this group that President López Obrador was talking about when he complained about their behavior at vaccination sites.

I flush with recognition but also defiance: where is the line between fighting for fairness — usually on behalf of oneself — and becoming hysterical in a way that hurts others rather than solves any kind of problem?

Is it better to just let things go, or is it better to fight for one’s rights?

I suspect that part of the reason for a baked-in cultural tendency to surrender in these instances is because there are plenty in which people here know that as mad as they may get, they simply won’t get the outcome they want. When there’s no reasonable expectation of justice, you can either accept it or die mad about it. And who wants to be mad all the time?

I’m personally working on my emotions about this myself, trying — unsuccessfully so far — to cultivate my own sense of Zen. I’ve received two packages over the past two months through FedEx: one, a returned cell phone from 2016 that I’d lent to a friend that made its way to the U.S. with her. It’s old and didn’t work very well anymore, but I asked for it back so that my kid could play with the camera on it.

I had to pay a Mexican customs fee of 830 pesos to get it. My argument to my friend that I shouldn’t have to pay to receive something that I lent out fell on deaf ears, so my choice was to either pay the ransom or lose the phone forever. I reluctantly paid, only to find that the “on” button no longer worked, rendering the phone useless. So, that was 830 pesos thrown into a black hole; I’m still mad about it.

I also had to pay (only 490 pesos this time!) to receive my dad’s small box of Christmas presents — he’s old-fashioned and likes to pick things out by hand in stores. I controlled myself as best as I could with the FedEx delivery guy — who I know is not at fault. But, of course, I couldn’t help telling him how unfair it was to have to pay to receive something.

“I hear that from a lot of people,” he replied, adding, “they have to get it out — and I’m the only person in front of them to be on the receiving end.”

I’m officially no longer accepting packages unless the customs fee is explicitly paid for.

I’ve had a few wins as well on the “customer justice” front: getting a lost domestic package replaced after hours on the phone when others had given up, convincing service people to help me out by using my own brand of relentless sweetness and very specific questioning until I wear them down.

For other things, I’ve learned to either let things go or stop participating: no one ever gets the rent deposit back, for example, so just let that slide and tell yourself you’re paying in advance for them to repaint and clean the place after you leave. But if a bank wants to charge me an annual fee so they can play with my money, they’re promptly abandoned. If a beer is flat, I’ll tell them, and maybe get a replacement.

In the end, the exact points at which one should both start fighting and then stop fighting are culturally specific, and I’m still trying to navigate where those lines are and should be. My guess is that, overall, we norteamericanos could learn a thing or two from our Mexican hosts about the art of letting things go.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sdevrieswritingandtranslating.com and her Patreon page.