Judy Wray is one of those people who can come to paradise and find a way to make it more beautiful.

“Paradise” is Wray’s word for Tepoztlán, a small town in a box canyon just south of Mexico City in the state of Morelos. It is a popular day and weekend destination and has a growing community of foreign residents from multiple countries.

She and husband Lazlo Krisch retired and moved there about 15 years ago. They traveled much of Mexico looking for the right place, and as soon as they entered the town they knew they had found it among its craggy peaks and New Age vibe.

Wray has made her mark in Tepoztlán by developing mural projects in the Santísima Trinidad neighborhood where she lives, recruiting her neighbors and even others from Mexico and abroad.

But to understand what she is doing in Tepoztlán, it is important to understand a little of her history.

Wray grew up in a creative household. Her mother encouraged her to be creative with whatever was lying around in the house, such as old camera flashbulbs, and also told her to “think big.” Wray is also part of the idealistic Baby Boomer/hippie generation.

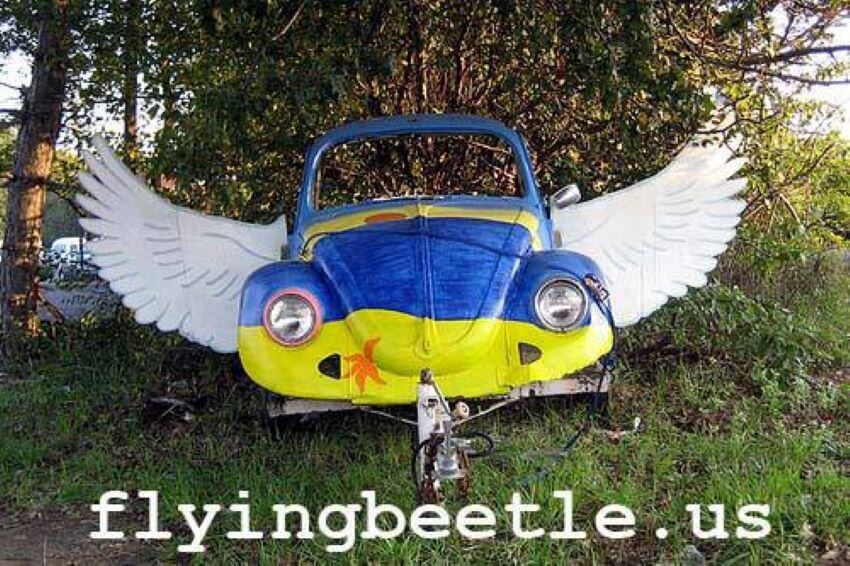

This generational influence is best seen in her logo for her website and organization Flying Beetle, which was founded to promote creativity in adults and children. The (original) Volkswagen Beetle with wings was part of a community mural project she organized in New Jersey at an auto repair shop. That particular mural later inspired projects with local schools creating magnets with children’s drawings on them and painting old hubcaps.

After moving to Mexico, Wray began similar projects here. She found audiences for projects, including a set of painted hubcaps that was exhibited at the Papalote Children’s Museum in Mexico City. But then she found another issue to tackle with art.

Despite being a paradise, life in Tepoztlán is not perfect. Even in her little neighborhood of La Santísima, there have been issues of vandalism and rising crime.

Wray’s answer to this was murals. Like she did in New Jersey, she has brought together community members and people in her artistic circles to create artworks that are designed by professionals but executed by regular people. One of Wray’s favorites is Maya and the Last Tree designed by Chiapas-based German artist Kiki Suarez, as part of a series called Cuentos en las Calles/Street Stories. Wray has also received design donations from Scottish artist Johanna Basford, Chilean artist Beatriz Aurora and Philippine artist Kerby Rosanes.

Wray has managed to get logistical support from cultural centers and even some sponsorship from the Comex paint company, but many of the expenses of the art projects still come out of her own pocket. She jokes about this, saying that if she were still in New Jersey, it would be money she would lose gambling in Atlantic City.

One of these expenses even includes paying a few people to help her, selected among those who are marginalized from Tepozotlán society for some reason. Another is taking advantage of the “cheap” (her word) graphic design and printing services in Mexico to create large tarp versions of the murals, which allow her to display the reproductions in other communities in a format reasonably faithful to the original.

Her murals are among many that exist in Tepoztlán today, but they are special because the community is involved in their making. They have had the intended effect of deterring graffiti and petty crime since people take more pride in where they live.

Another advantage La Santísimas has, according to Wray, is that it is paved in cobblestone. This forces people to drive slowly and appreciate the work.

About two years ago, Wray found a new way to be creative. She rents her living space in a compound owned by a traditional Mexican family. One is a healer, who always has people in the courtyard waiting to be seen. She decided to take advantage of this, asking the patients to color line drawings done by Johanna Basford.

The results were so good that she had the drawings transferred to ceramic tiles to be placed on school bus stops and other areas where students often hang out. The tiles were made by UniqueTiles Ltd. in the United Kingdom; she tried to find someone in Mexico to do it but without luck.

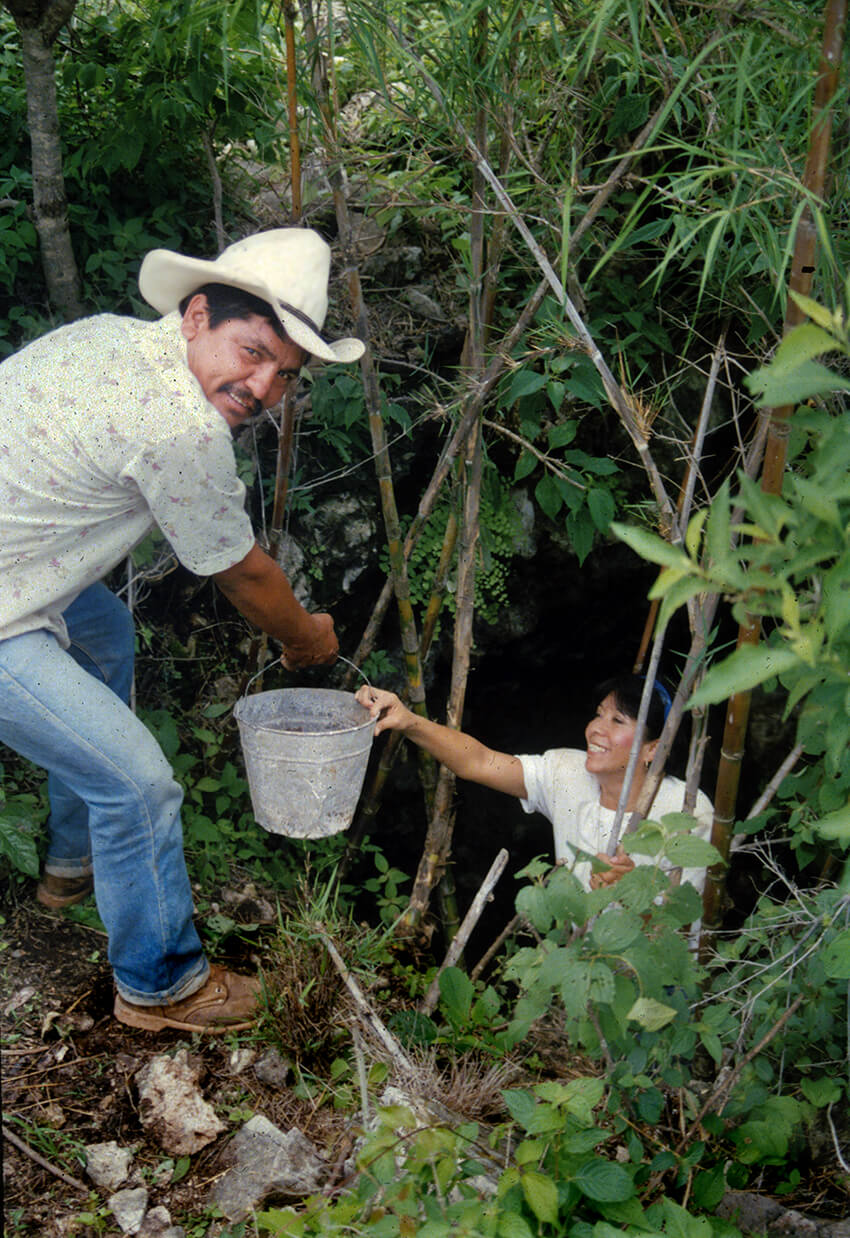

Today, Wray’s main assistant is Tepoztlán native Sara Palacios. She began working for Wray out of necessity, but over the last few years, the two women have formed a close friendship, despite the differences in age, nationality and language.

“Sara understands my heart,” Wray says.

Despite her advancing age, Wray has no plans to slow down. “At age 75, I’m at the end of my life, but I am having a ball,” she says.

To see much of Judy Wray’s work, visit her Flying Beetle website.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.