A drug cartel is attempting to shut down live music performances at a popular fair in the state of México.

On Friday morning, narco banners appeared around the city of Metepec threatening the lives of any musicians who dared to perform at the 2021 Metepec Fair, in a possible case of unpaid extortion.

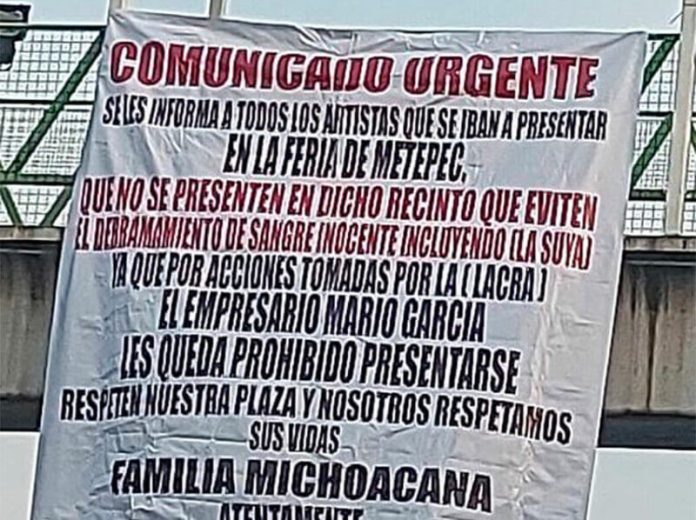

The banners, signed by the Familia Michoacana, were hung from overpasses and directed at the fair promoter Mario García.

“Urgent message: We inform all the artists who were going to perform in the Metepec Fair not to perform at that venue, to avoid the spilling of innocent blood including theirs … due to the actions of that bum, the businessman Mario García, they are prohibited from performing. Respect our organization and we will respect your lives. Familia Michoacana,” read the banners.

The fair started with a performance by El Komander on October 29 and is scheduled to continue through November 14, with shows by many prominent musicians including La Sonora Dinamita, La Arrolladora Banda El Limón, Christian Nodal, Julión Álvarez and more.

On the opening day, the state government suspended proceedings for several hours due to missing permits and security measures, but eventually allowed the event to proceed.

So far, neither municipal authorities nor the fair organizers have made statements as to whether the fair will be suspended.

The threats follow a Thursday confrontation between police and presumed members of the Familia Michoacana in southern México state. The incident left two officers dead and six injured.

With reports from Reforma and Plana Mayor