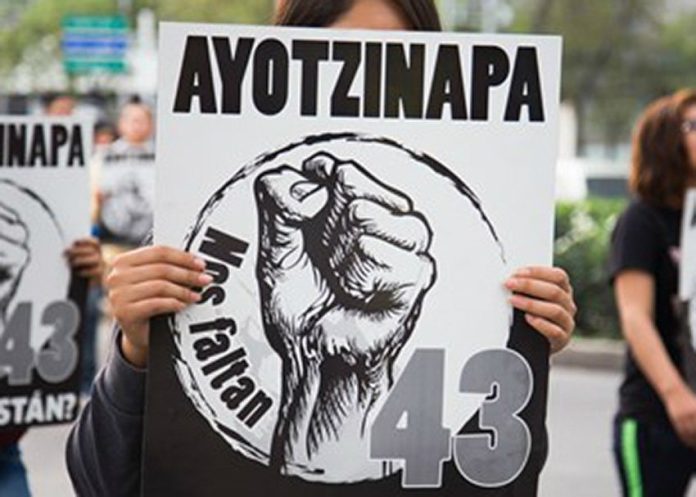

The unsolved disappearance of 43 students from a rural teachers college in Mexico four years ago put the level of collusion between the country’s organized crime groups and security forces on stark display, but questions remain as to whether the incoming administration will be able to tackle it.

On the evening of September 26, 2014, 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College disappeared in the city of Iguala in the western state of Guerrero.

A few months later, in January 2015, the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto said that police in Iguala had arrested the students and handed them over to a local crime group known as the Guerrero Unidos.

One of the group’s leaders later testified that he ordered the students to be killed and their bodies later burned in a trash dump in the nearby town of Cocula, a version of events that investigations conducted by independent experts have cast serious doubt on.

One theory as to why the Guerreros Unidos would target a group of students says that one of the buses the students had taken to travel to a protest was allegedly carrying a heroin shipment, which ultimately prompted the deadly response from security forces and members of the criminal group.

The investigation into the whereabouts of the 43 students has been marked by irregularities and mismanagement. A March 2018 United Nations report accused the Mexican government of fabricating evidence and torturing many of the individuals it arrested into confessing to involvement in the crime, in addition to trying to cover up these abuses.

Shortly after winning the election in July, president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador requested an international team of experts to return to the country to continue an investigation largely dismissed by Peña Nieto and ordered the creation of a truth and justice commission to reopen the case.

InSight Crime analysis

The case of the missing 43 students will undeniably be Peña Nieto’s darkest legacy as he leaves office and López Obrador replaces him in December. But whether the incoming president will be able to both solve the case and effectively reform the security forces that so often help facilitate criminal activities in the country remains to be seen.

Aside from showcasing the Mexican government’s inability, or unwillingness, to adequately investigate and handle crucial evidence in a high-profile investigation, the Ayotzinapa case also illustrates the depth of collusion between organized crime groups and security forces.

As Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández and her colleague Steve Fisher uncovered, drug traffickers associated with the Beltran Leyva Organization kept local and federal security forces in Iguala on their payroll, and ordered them to recover the shipment of heroin that was allegedly on the bus the students had taken that fateful night in September 2014.

The students seem to have been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Uncovering what happened to them would mean shining the spotlight on security forces’ collusion with organized crime groups — and the government turning a blind eye to it — something that would have further contributed to the widespread disapproval of Peña Nieto’s fight against crime and drug trafficking.

In an effort to strengthen the institutions directly affected by organized crime, López Obrador promises to ensure the county’s police force is better trained, better paid and more professional.

This is a welcome step as Mexico’s police are largely overworked, underpaid and understaffed, which can at times leave them entirely dysfunctional and more susceptible to corruption and infiltration from organized crime groups.

But while addressing the shortcomings within the police is needed, it likely won’t entirely eliminate the corruption within these institutions that crime groups so often rely on to operate.

“It’s not enough to just have a police force that is better trained and better equipped to fight organized crime,” Christy Thornton, an assistant professor in sociology and Latin American studies at Johns Hopkins University, told InSight Crime.

“This doesn’t take away the financial incentive for crime groups to move drugs through these areas, which comes from demand in the United States. As long as that incentive exists, crime groups will seek collusion from security forces or at least the guarantee that they’ll look the other way.”

As InSight Crime previously reported, López Obrador will have to “avoid grand solutions” and instead focus on the many moving parts that impact Mexico’s security situation if things are to improve.

One of the most important places to start, according to Jaime López, a security policy consultant and former Mexican police officer, is “strengthening internal oversight mechanisms [within security forces] throughout the country.”

So far, López Obrador has failed to provide a concrete plan for how he might attempt to improve oversight mechanisms and other factors that could reduce levels of corruption within the country’s security institutions.

“The new administration might be able to push for coordinated efforts in this direction, but it would take a much more detailed diagnosis and more specific strategies than what we have seen so far,” López added.

López Obrador seems to have the political will to find the answers that Peña Nieto’s administration failed to regarding the 43 missing students, but rooting out the corruption within the country’s security institutions that helped facilitate this egregious crime may prove to be a much harder task.

Reprinted from InSight Crime. Parker Asmann is a writer with InSight Crime, a foundation dedicated to the study of organized crime.