The approval by federal Congress of a bill that has significant ramifications for Mexico’s science and research sector triggered a strike this week as well as criticism from numerous members of the scientific community.

In the early hours of last Saturday morning, senators with the ruling Morena party and its allies voted in favor of the creation of a new General Law on Humanities, Science, Technology and Innovation (LGHCTI), which was initially proposed by President López Obrador last December.

The bill, one of about 20 pieces of legislation approved during a frenzied Senate session that began Friday night, was subsequently sent to the president for promulgation.

There was no debate before the vote took place, and opposition senators didn’t attend the legislative session, which was held in an alternative venue due to an unrelated protest in the Senate chamber.

According to the National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt), approval of the LGHCTI is a “milestone in the history of the country” as the law protects the “human right to science and knowledge.”

Conacyt will become the National Council of Humanities, Science and Technology (Conahcyt) once the new law takes effect.

Critics of the law have denounced its centralization of decision-making in the academic sphere and its curtailing of the autonomy of public research centers. They have also pointed out that an existing goal of investing 1% of GDP in scientific research is absent in the new law, and criticized the inclusion of military representatives on a board that will make decisions about funding for various academic projects.

Students and academics from institutes including the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics and the National Autonomous University (UNAM) joined a so-called paro nacional, or national strike, on Tuesday. Mexico City, Yucatán and Morelos were among the federal entities where stoppages took place.

Conahcyt, once it is established, will have a 20-person governing board whose members will be officials from numerous ministries including those of Agriculture, Welfare, Culture, Economy, Education, Foreign Relations, National Defense and the Navy. The allocation of seats at the board’s table to the military – which has been given responsibility for a wide range of non-traditional tasks in the current government – is a particular point of contention.

Representatives of civil society organizations, business groups and state and municipal governments will not have a say in how Conahcyt is run and which academic projects receive government funding.

Antonio Lazcano, a biologist and emeritus UNAM professor, told the newspaper El País that the way in which the bill was approved was disgraceful and indicative of the “irresponsibility” of lawmakers.

Most senators hadn’t even read the 112-page bill before the vote took place, according to El País, and just two of seven scheduled “open parliament” sessions on the bill – at which interested citizens have the opportunity to voice concerns – went ahead as planned.

Alma Maldonado, an academic at the Center for Research and Advanced studies at the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), described the process – or lack thereof – to approve the bill as “sloppy” and “very clumsy.”

She said that the new law will “subordinate” scientific institutes and agencies to Conahcyt because they will be dependent on the decisions taken by that organization’s board.

Brenda Valderrama, a researcher at the UNAM Institute of Biotechnology, said that the power to take decisions about issues related to science in Mexico will be concentrated in “a handful of officials.”

Lazcano asserted that the bill that passed the Senate has “brutal defects” and represents an attempt to bring political ideology into science. Martín Aluja, an entomologist, offered a similar view, asserting that what passed Congress is not a “general law” but rather “a political manifesto.”

Luis Omar Montoya Arias, a historian, asserted that the approval of the LGHCTI is “another step toward the militarization of the country,” while the president of the Mexican Association for the Advancement of Science said that the new law will likely face legal challenges given that the process by which it was approved was “full of legislative procedural flaws.”

Alma Cristal Hernández Mondragón, who is also a policy specialist at the IPN’s Center for Research and Advanced studies, expressed concern about the exclusion of “voices that can contribute” to policy debates, given that all Conahcyt board members will be government officials.

David René Romero Camarena, a genome scientist at UNAM, said that the LGHCTI favors public universities, and, as a result, researchers and students at private institutions will be treated in a “discriminatory” way once the law takes effect.

The federal government, however, has argued that the law is “needed to streamline policymaking and bolster government support for basic and applied research,” according to a news report by the academic journal Science.

The journal also reported that “some scientists are encouraged by provisions that call for work on behalf of the environment and disadvantaged communities.”

Martha Ileana Espejel Carbajal, a social ecologist who until recently was a professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California, said that the LGHCTI will “help many who were not privileged before.”

“It is the first time in 40 years of being a research professor that the law asks [us] to do what my team has always struggled to defend: … work with the most marginalized communities, with women, with youth, with social and ecological systems,” she said.

The LGHCTI may have flaws, but “every law is perfectible,” Espejel said.

In a statement issued after last Saturday’s vote, Conacyt said that the LGHCTI has a “humanistic focus that frames and guides scientific progress and technological development in favor of social wellbeing and environmental care.”

It also said that the law will strengthen Conacyt (or Conahcyt) and the 26 public research centers it manages.

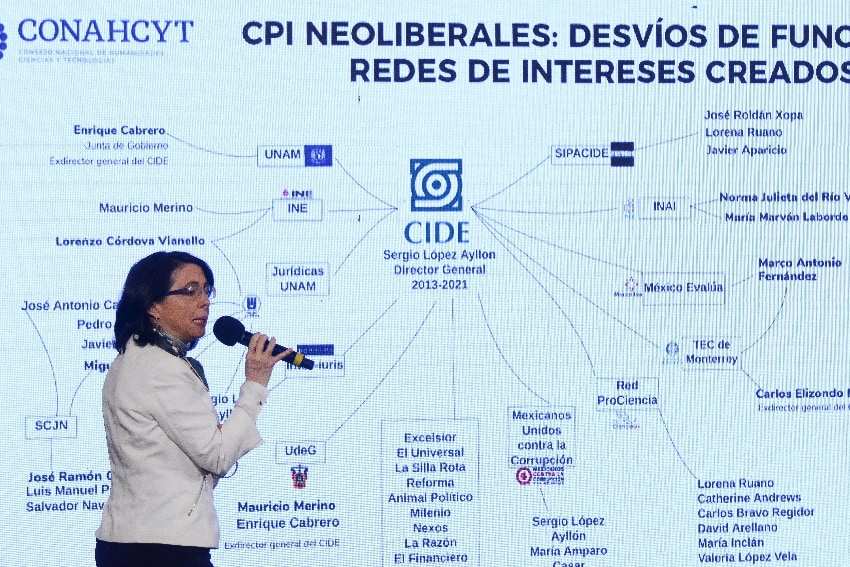

“With the creation of this … General Law, Mexico breaks the paradigm, which, in the past three six-year periods [of federal government], permitted the use of public resources to fund a great quantity of private projects that simulated [rather than actually carried out] research,” Conacyt said.

“… This LGHCTI mandates mechanisms that prevent … resources of the people of Mexico … being transferred to … vested interests, … taking care that each peso allocated to the funding of HCTI activities is used in strict accordance with the [established] guidelines,” it added.

With reports from El País, Sin Embargo, El Financiero, Crónica and Science