“It is nonsense and inconceivable, the accusation of criminal association against members of the scientific community.” Those were the words of Enrique Graue, rector of Mexico’s National Autonomous University (UNAM), referring last week to the federal Attorney General’s Office wish that 31 scientific researchers be locked up in a maximum-security federal prison.

Thirty-one people, many of them prestigious scientific researchers, have been accused of embezzlement, illegal use of attributions and authority, activities involving financial resources of illicit origin and organized crime. Ten women and 21 men for whom their right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty was apparently not granted and whose reputations have been seriously damaged.

The federal Attorney General’s Office has asked a judge to lock them up in the Altiplano maximum-security federal prison in México state — where some of the nation’s most notorious and dangerous criminals are held.

As far as I know, something like this has never happened anywhere in the free world.

Several important public and private Mexican universities — among them Mexico’s UNAM, the Metropolitan Autonomous University, the Ibero-American University and the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Studies, my alma mater — publicly condemned and rejected what will undoubtedly go into the history books as Mexico’s most shameful episode about politics and science.

Even prominent members of President López Obrador’s political party Morena have sharply criticized these nonsense actions, including Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum and Morena’s leader in the Senate, Ricardo Monreal.

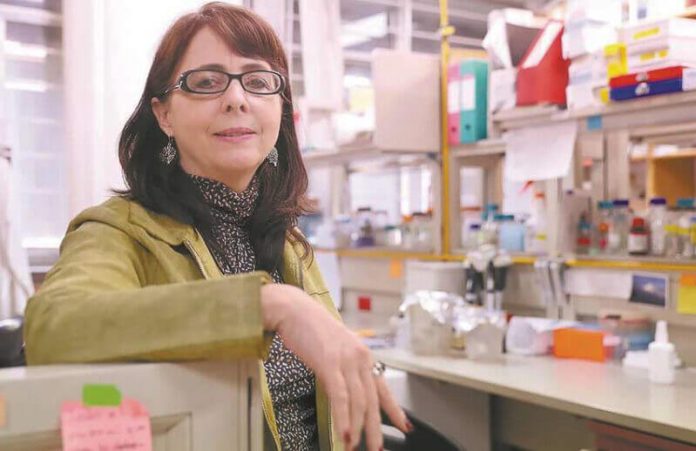

I haven’t had the opportunity to personally meet María Elena Álvarez-Buylla, director of the National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt). I have asked her twice for an interview in writing but unfortunately not gotten a response. The first time was about a year ago, and the second was last week because of recent events.

My interest in interviewing her is to engage in a respectful and transparent dialogue like the ones I have had with senior members of the current administration such as former environment minister Víctor Toledo and Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister Martha Delgado, both of which were published in the newspaper El Universal.

I wanted to ask Álvarez-Buylla about her vision for Conacyt, its accomplishments, opportunities and challenges. And, of course, I now also want to inquire about her involvement in the accusations against those 31 scientists associated with the Science and Technology Advisory Forum, an autonomous consulting body established in 2002 to advise Conacyt’s board of directors.

Conacyt is responsible for establishing national public policy on humanities, science, technology and innovation. Its mission is to develop and strengthen capacities in those spheres through projects linked to research and the capacity-building of academics and researchers.

It has a network of 26 internationally renowned public research centers and each year grants more than 85,000 postgraduate, doctoral and postdoctoral fellowships to study both in Mexico and abroad. Conacyt also encourages (through financial incentives) the scientific work of more than 30,000 researchers and has a community of 2,000 young researchers who work in various public institutions throughout Mexico.

Beyond all doubt, Conacyt is the most important governmental institution that supports science, technological development and innovation in Mexico.

But just who was Álvarez-Buylla before being appointed by President López Obrador to lead Conacyt? I offer below a brief summary of the most relevant details of her professional trajectory (taken from the webpage for UNAM’s Institute of Ecology, where she worked before and presumably will return after leaving the government). These aspects of her career contrast sharply with some of the most ill-fated decisions of her tenure at Conacyt.

Álvarez-Buylla has for many years worked in molecular genetics and developmental evolutionary ecology. She has an undergraduate degree in biology, a master’s in sciences from UNAM, a doctorate in botany, and has done postdoctoral research at the University of California’s Berkeley and La Jolla campuses. In 1992, she rejoined UNAM’s Institute of Ecology as a full-time researcher. (She is currently on an unpaid leave of absence.)

Since 2001, she has maintained the highest level (III) within the National Researchers System and the highest level (D) in a program that UNAM offers to its full-time professors and she has given talks at more than 139 national and international scientific meetings and symposia (participating in the organization of many of them).

Álvarez-Buylla has contributed to the training of new researchers by guiding the work of undergraduate, master’s and doctoral students, and she has taught undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Many of her students and collaborators are researchers at prestigious universities abroad.

She has won many awards and scholarships nationally and internationally, including Mexico’s National Science Award in 2017.

It is, then, in the context of her long and distinguished scientific and academic career and of her tenure at Conacyt, and in view of the appalling events of the last two weeks, that I wanted to respectfully ask her a few questions:

What are Conacyt’s main achievements and challenges after three years under your directorship? What has worked and what hasn’t and why? What kind of legacy would you hope to leave to your successor?

What is your vision of science, and what, exactly, are you referring to when talking about “neoliberal science,” which you blame for much of what hasn’t worked in Mexico?

How do you see yourself going back to your scientific and academic activities the day after you have left a privileged position from where you disqualified scientists and academics who thought differently than you? What would you say to your peers if they accused you of undermining Conacyt and polarizing it against Mexico’s scientific community?

How will you defend yourself to your colleagues and students at UNAM, to other universities and institutions and to the Mexican public for having personally advocated for the elimination of trust funds and programs that supported scientific and technological research, drastically reduced or abolished many of the scholarships and financial support for Mexican students attending international universities and having sharply reduced government funding for researchers across the country to participate in scientific meetings?

And how would you answer your students, past and future ones, when they ask you — and they certainly will — about the role that Conacyt, according to media reports, presumably played in trying to lock up 31 of your scientific and academic peers in a federal maximum-security jail?

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.