Since establishing diplomatic relations in 1972, Mexico and China have maintained a cordial political relationship.

However, economically the two countries have remained competitive for the last three decades. Consider that in 2001 Mexico was the last country to withdraw objections against China’s accession to the WTO.

Times have changed though. Recently, bilateral engagement between Beijing and Mexico City has become more complimentary.

In September 2017, President Enrique Peña Nieto held another round of bilateral meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping, the seventh such meeting since 2013, when both leaders agreed to declare the status of the Sino-Mexican relationship as a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

With Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s landslide victory in the Mexican election on July 1, the Sino-Mexican partnership will almost certainly deepen further for three reasons.

First, Mexico may not feel that waiting for NAFTA is a winning economic strategy. As of May 17, United States House Speaker Paul Ryan’s informal deadline, NAFTA renegotiations were still in limbo. Worse, on June 1 the Trump administration delivered a gut punch to America’s closest allies, imposing tariffs on steel and aluminum from Europe, Mexico and Canada.

Four days later, Mexico retaliated with new tariffs on U.S. products. The list of taxed goods includes whiskey, cheese, steel, bourbon and pork. Canada has even been pushing the trans-mountain pipeline to sell oil directly to China.

“Mexico is realizing that it has been overexposed to the U.S., and it’s now trying to hedge its bets,” according to Kevin Gallagher, professor at Boston University. Currently, China is Mexico’s fourth-largest trading partner, accounting for US $6.7 billion of Mexico’s annual exports.

These numbers are far smaller than Mexico’s exports to the United States, which account for $372.4 billion of Mexico’s annual exports. Recognizing that Mexico is overly reliant on the U.S., there have already been moves towards deeper integration with China.

In early 2017, while the U.S. and Mexico were preparing for NAFTA renegotiations, billionaire Carlos Slim went ahead and established joint ventures with China’s JAC Motors, one of three automotive companies owned by the Chinese government with a presence in Mexico.

The Chinese have reciprocated as well. Last September, Xi Jinping called Mexico an “important pivot of the natural extension of Belt and Road construction in Latin America” and said both countries should synergize development strategies.

In fact, China invited Mexico as one of five nations to consider a “BRICS plus” arrangement, which would add new members of the global South to the now five-country grouping. López Obrador can easily jump on the bandwagon of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) should he want to more fully pivot towards Beijing and away from Washington.

Second, López Obrador can also take advantage of China’s patient capital, an important form of state-led capitalism and characterized by a longer-term horizon. Historically, Chinese efforts at major projects in Mexico have not been fruitful.

Beijing tried to champion a high-speed rail link to connect Mexico City and the city of Querétaro. However, President Enrique Peña Nieto was forced to scrap a contract awarded to a consortium led by China Railway Construction Corp. after an outcry over transparency.

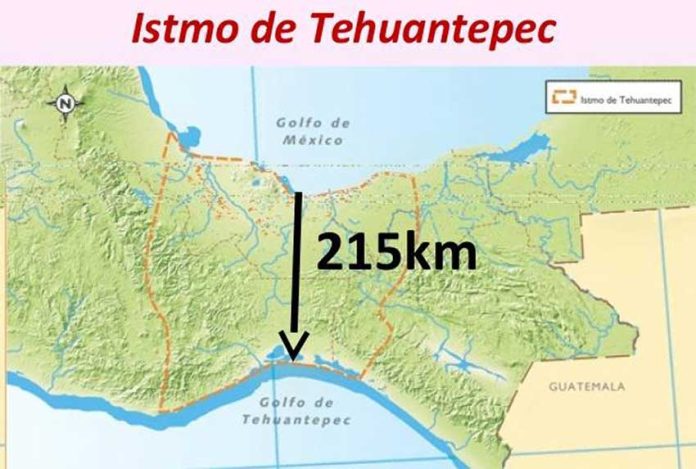

With López Obrador, China may have another shot at a big project in Mexico. The new Mexican president has ambitions to revitalize a rail corridor across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, where the Atlantic and Pacific oceans are just 200 kilometers apart. In theory, this would serve as a Panama Canal-lite, opening up a short cut to the Atlantic.

The corridor would not only provide an alternative route — allowing cargo to avoid the Panama Canal, which is more than 2,000 kilometers to the south — but it would also give businesses a reason to locate in Mexico’s depressed south.

Such a project is expected to cost $7 billion in the first year alone and require a combination of public and private funding. “I can see us perfectly well approaching the Chinese, above all. It’s the type of project they will certainly want to invest in, because they are long-term infrastructure projects with clearly positive returns,” according to Gerardo Esquivel, a Harvard-trained economist and one of López Obrador’s economic advisers.

Third, López Obrador can get on Beijing’s good side by helping transform China’s image in Latin America. By investing in the “new Silk Road” trade corridors spanning 65 countries, Beijing is trying to move beyond its traditional focus on resource extraction.

Panama is a great example of a country where this is happening. Five months after China and Panama established official diplomatic relations, Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela Rodríguez visited Beijing in November of 2017. One of the most important agreements they concluded is the inclusion of Panama in the BRI.

Going forward, Panama will likely play a key part in China’s efforts in Latin America, with the Panama Canal and the country’s strong financial and logistics platforms giving China key infrastructure capabilities in the region.

Likewise, Mexico can help China to transform the traditional extractive model of investment into a more productive one. In fact, China has also already taken advantage of recent energy reform in Mexico, which opened the door to foreign investment in the industry.

The state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation plans to invest $8 billion in Mexico over the next 30 years, indicating that both countries want to move the relationship forward. Mexico can enhance its connectivity with Asia through projects such as the “Made in China 2025.”

Former Mexican foreign secretary Jorge Castañeda once characterized Mexico’s growing interest in China as an “expression of machismo” directed against the United States.

If President López Obrador really wants to show his “machismo,” then he should follow in the footsteps of Peru’s former president, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who chose China as the first foreign country he visited.

Indeed, if López Obrador makes a strong move towards China, Beijing will most likely reward him no later than the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) meeting in 2019 to be held in Chengdu, capital of southwestern Sichuan province.

The writer is professor and director of the Center for Latin American Economy and Trade Studies at Chihlee University of Technology, Taiwan.