On March 26, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as AMLO, said he had sent a letter to Spanish King Felipe VI asking him to consider the possibility that the Spanish state apologize for the abuses committed by the Spaniards during the conquista.

A similar letter was also sent to Pope Francis, asking for an apology from the Catholic Church. The reason is “thousands of people were killed . . . one culture, one civilization imposed itself on another.” The government of Spain has “vigorously” rejected the request.

AMLO’s gesture was likely designed to portray Mexico as a moral country and to seek a historic reconciliation. However, it is long past time for the Mexican government to apologize to the Chinese-Mexican community. Doing so would not only help heal deep historical wounds, it would lay the foundations for a stronger Mexican foreign policy going forward.

Mexico has an oft-ignored history of discriminating against Chinese immigrants. “Chinese-Mexicans are nearly absent from the Mexican national narrative,” according to Grace Peña Delgado, professor at UC Santa Cruz. An anti-Chinese movement emerged during the Mexican Revolution and attained peak influence before and during the Great Depression.

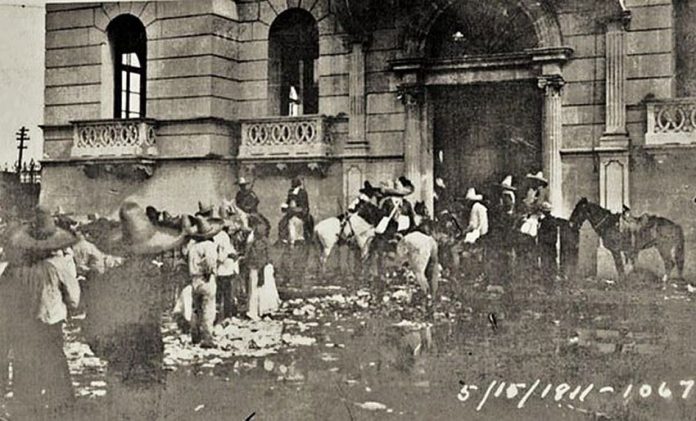

While most of Mexico’s anti-Chinese groups were formed between 1922 and 1927, there was a significant amount of animosity against the Chinese prior to the 20s. Perhaps the most violent single episode occurred on May 15, 1911, when Mexican revolutionary forces massacred over 300 people of Chinese descent in the city of Torreón, Coahuila.

Popular Mexican politicians of the time often fanned the flames of xenophobia. For example, as one of the most prominent national politicians of the era, Plutarco Elías Calles had held strong anti-Chinese leanings since his days as a Sonoran state politician.

Known as “the Maximato,” his powerful position made it easier to expel Chinese with impunity. Not only did he support a special tax on Chinese farmers and merchants in the agricultural towns around the capital, he denied reentry permits to those people of Chinese descent who had traveled to China.

Later, in 1931, his son, Rodolfo Elías Calles, assumed the governorship of Sonora and formed “rural brigades” to search for Chinese hiding in the countryside.

As a result of the violence and discrimination, Mexico witnessed a mass exodus of people of Chinese descent. Some 70% of Chinese-Mexicans were expelled to China or, ironically, the United States. While repatriation efforts began almost immediately and lasted until the 1980s, the legacy of the hatred is hard to erase.

A formal Mexican government apology at this particular moment can achieve multiple purposes. First, it would strengthen Mexico’s moral argument in lobbying for immigration reform in the United States. In his book Oye Trump (Listen up, Trump), AMLO outlined what was wrong with Donald Trump’s position with Mexico and its citizens.

However, after Trump accused Mexico of actively contributing to an “onslaught” of immigrants during his State of the Union address, AMLO simply said he respected his point of view. Should he choose to make amends for a particularly xenophobic period of Mexican history, AMLO would pose a powerful moral challenge to the American president to take immigration reform seriously.

Second, such a gesture would be good global statesmanship. Mexico may not feel that the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement is a winning economic strategy. Jorge G. Castañeda, Mexico’s foreign minister from 2000 to 2003, said “I can offer an informed guess: the United States gave up most of its trade demands in exchange for a confidential commitment by Mexico to do Washington’s dirty work against would-be immigrants and refugees.”

Arguably, diversifying trade can reduce Mexican economic dependence on the United States and their exposure to a potential global trade war. AMLO can take advantage of China’s patient capital, an important form of state-led capitalism characterized by a longer-term horizon.

An apology would display a commitment to liberal values while at the same time signal a greater level of friendliness towards China.

In some ways, AMLO would be following in the footsteps of his North American Free Trade Agreement counterparts. In 2006, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a full apology to Chinese-Canadians for the head tax and expressed his deepest sorrow for the subsequent exclusion of Chinese immigrants from 1923 until 1947.

Similarly, in October of 2011, the U.S. Senate approved a resolution apologizing for past discriminatory laws that exclusively targeted Chinese immigrants, in particular the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In June of 2012, the U.S. House of Representatives also passed a resolution expressing regret for past discriminatory laws. This apology came on a resolution sponsored by Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.), the first Chinese-American woman elected to Congress.

Making amends for Mexico’s xenophobic past can pay dividends for the country’s future relations with China. As a gesture of goodwill, it can be sold domestically as a sort of prepaid “pilón.” There is a neat historical symmetry here. Historically, pilón has been an important part of Chinese businesses in Sonora.

It refers to the tip of a cone of piloncillo, or brown sugar in a crystallized form. Chinese business owners in Sonora regularly gave their customers some sort of pilón or small gift with a purchase.

The Sino-Mexican relationship is one with high stakes. An apology served as pilón may be a small price to pay in order to advance Mexico’s moral standing in the world and economic interests with China.

The writer is professor and director of the Center for Latin American Economy and Trade Studies at Chihlee University of Technology, Taiwan, and an occasional contributor to Mexico News Daily.